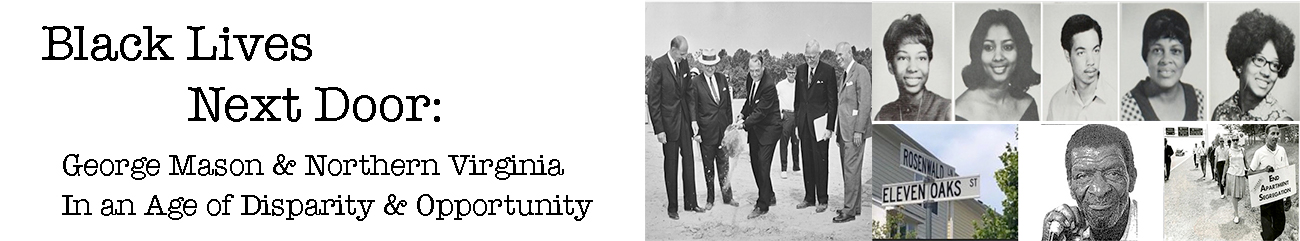

Bulldozers, Black Lives, White Suburbs: Removing Earth and Memory

After 1945, a “culture of clearance” altered the face of Fairfax County. With the bulldozer becoming the symbol of “destruct[ive] . . . progress,” middle-class suburbs emerged on razed ground.[1] The fifteen-year-old John Tilghman Hazel Jr. (who went by the nickname Til) watched this process unfold. He saw heavy machines build a subdivision called Pimmit Hills, which is now located inside the Capital Beltway. “[I]t hit me,” Til Hazel reported, that countryside seven miles from the future George Mason University “was changing” irrevocably “and this was a good thing.”[2]

The transformation of farms and fields into bedroom communities made Fairfax a site of white prosperity and Black displacement. By the 1940s, longstanding African American communities were being pushed out of the county. A report published in 1970 by the Washington Suburban Institute found that systemic racism was at fault because “low income [Black] people” were being excluded “from housing and jobs.”[3] Local politicians ignored the conclusion, choosing instead to downplay histories of inequality spurring the growth of townhomes and single-family houses. The ubiquitous subdivision counted most. It was welcoming white professionals with mortgages who worked in federal agencies and area corporations contracted to help America win the Cold War.[4]

Historians are beginning to reconsider critically how market influences, institutional opportunities, and enduring Jim Crow discrimination reshaped Northern Virginia.[5] While current research is examining the mix of these three forces and their impact on struggles over new construction, it is notable that scholars have not focused on land developers like Til Hazel, the booster of George Mason College (GMC) who scorned “people of modest vision” as “anti everything.”[6] He envisioned Fairfax revolving around a major university with the educational and functional capacity to catalyze America's great government suburb.

Established county residents reacted in different ways to Til Hazel's innovation and ambition. Edith Elliot, the daughter of GMC's “Farr tract” donor, was certainly not one of his admirers. She wrote the college president, Edgar Shannon, about the agent of property “condemnation” named “John T. Hazel.” Her letter vented “emotions [that] ran the gamut from shock to grief to sheer fury.” On 5 August 1970 Edith Farr Elliot had “witnessed an unforgettable sight.” She observed “bulldozers . . . flattening . . . more acreage of ‘our’ land at George Mason College.” The “ground leveling” obliterated century-old trees at “the corner of Braddock Road and Ox Road (Route 123)” where “the loveliest” glade once existed with her “family home . . . [prior to the residence being] burned by federal troops in 1862.” Now all was gone, including the "laurel, holly, and dogwood.” Edith Farr Elliot lamented the loss of natural beauty and its desolate replacement; yet “another vast parking area.” That “[t]ons of earth will have to be moved” worsened her “bitter” blow. Why is this happening, she asked, before giving her answer: “the word favored by people in this business” of development “is 'functional', but is it even that?”[7]

By George Oberle and Benedict Carton

[1] Francesca Russello Ammon, Bulldozer: Demolition and Clearance of the Postwar Landscape (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 3.

[2] Russ Banham, The Fight for Fairfax: A Struggle for a Great American County, 2nd ed. (Fairfax: George Mason University Press, 2020), 3.

[3] Thomas Grubisich and Washington Post Staff Writer, “Fairfax Growing Whiter: Fairfax Experiences Institutional Racism,” The Washington Post, Times Herald (1959-1973), October 29, 1970, F1.

[4] Andrew Friedman, Covert Capital: Landscapes of Denial and the Making of U.S. Empire in the Suburbs of Northern Virginia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 37.

[5] Russ Banham, The Fight for Fairfax: A Struggle for a Great American County, 2nd ed. (Fairfax: George Mason University Press, 2020), ix.

[6] Hazel, John "Til," Interview by Christine Widmayer, with Bob Vay, 20 April 2011, George Mason University Oral History Project, Collection #R0095, Special Collections and Research Center, George Mason University, Fairfax.

[7] Letter, Edith Elliot, Fairfax, to Dr. Shannon, Fairfax, 5 August 1970, Folder 16, Box 14, Early History, Office of the President, Special Collections & Archives, Special Collections Research Center, University Libraries, George Mason University, Fairfax, Virginia.