From Slave Day to Derby Days: Racial Ridicule in Northern Virginia and GMU

The legacy of slavery in the region of Northern Virginia takes different forms. Acts of cultural performance and ritualistic events demonstrate the legacy of slavery, and perpetuate forms of racialized violence in the region. Over decades spanning throughout the mid- to late-19th century – and still into the 20th century – racialized cultural and ritualistic practices took the form of minstrel shows, blackface, and slave sales. These were all used as comedic, ironic, or entertaining performances for white and non-Black audiences. This culture of racialized othering through grotesque, caricaturized and stereotyping visual representations of race created a culture of racial ridicule.

Racial ridicule became a part of white culture in the Northern Virginia (among countless other regions throughout the nation) and is implicit as part of the regions culture due to the commonality of whiteness, and white inhabitants’ actions as the cultural hegemon. While the history of post-slavery racial ridicule lasts from emancipation until the present, the focus of this research is on mid- to late-20th century Northern Virginia, and racial ridicule in the culture of the growing Fairfax County and its students. Here it is argued that throughout the mid-20th Century, as Northern Virginia grew into the sprawling suburban megalopolis on the doorstep of Washington DC, the culture of racial ridicule festered throughout local high schools and spread into the culture of colleges, such as the newly founded George Mason College (now George Mason University), where into the late-20th century it remained even after attempts to challenge the culture in institutional structures and societal actions.

Racial ridicule as a term has generally been used in few cases. While fellow CML researcher Ky Buckner has employed the term in their own work (see footnotes 2 and 13), the term also exists in the legal realm as part of Connecticut’s General Statutes. Under Section 53-57, racial ridicule is legally defined as such: “Any person who, by his advertisement, ridicules or holds up to contempt any person or class of persons, on account of the creed, religion, color, denomination, nationality or race of such person or class of persons, shall be guilty of a class D misdemeanor.”[1] Created over a century ago, the law exists in murky legal waters, and has faced recent checks on validity due to its potential overstepping of boundaries of the First Amendment.

Racial ridicule is defined here as an extension of Patricia Hill Collins’ idea of controlling images. Thus, racial ridicule is the maintenance of hierarchical orders of white supremacy by way of invoking controlling images that seek to dominate and perpetuate racialized violence and racialized tropes. These controlling images build racial ridicule through quotidian actions that racialize interactions, and in displays of social relations of domination.[2] These actions and social relations work to ridicule and shame or belittle those who do not fit into the hierarchical positions of power attained through whiteness directly or indirectly through micro- or macroaggressions upon, or racialized treatment of others.

The controlling imagery of slave sales as a fundraiser sustains hierarchical power, and the act of blackface performances utilizing Black women’s features - as two examples - further political domination and the primacy of whiteness. While these harmful, hurtful and shaming actions get refashioned into something told as harmless fun, they invoke ideas about racist pasts, violent histories, and Black peoples’ bodies, behaviors, and appearances that all create a system of racial ridicule. This racial ridicule perpetuates political domination and hierarchies. While this research mainly discusses anti-Blackness in relation to racial ridicule, the idea of ridicule and its controlling images and structures expand further through intersecting systems of power - affecting other social groups outside of the typical Black/white binary who encountered controlling images created to ridicule them both in Northern Virginia's education system and in Northern Virginia's culture at large.[3]

During the 20th Century in Northern Virginia racial ridicule through slave sales as fundraisers, blackface in fraternity gatherings and activities, sexist and racist representations of race, and targeting of minority students through racist hazing and imageries acted as part of the culture of Northern Virginia and its education system/institutions. These actions represented the broader culture of the region – a white hegemonic order, predicated on the history of racism, segregation and slavery. Though the literature racism, segregation in society and institutions, representations of race, and the history of racialized cultural events like minstrelsy is broad, the study of racial ridicule is largely missing in the historiography of the 20th century Northern Virginia and the broader era of suburbanization and developing modern America. An inspection of Northern Virginia, and its culture of racial ridicule is therefore necessary.

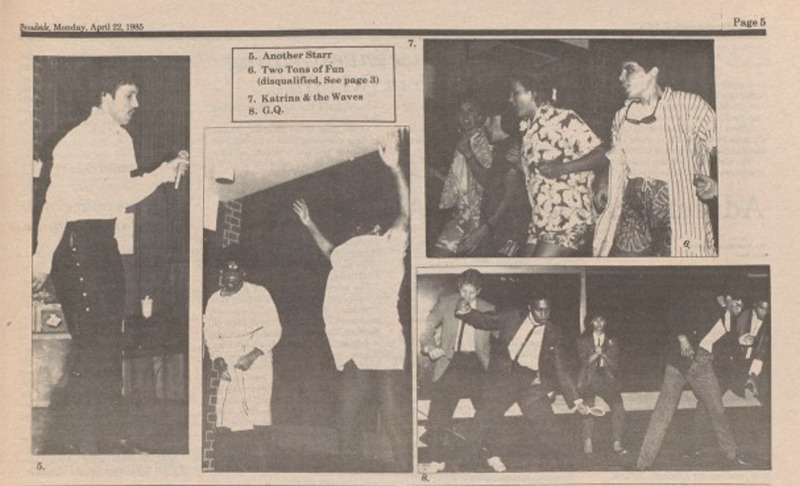

Through focusing on high schools, George Mason College (later George Mason University) and its students, this study tracks the use of racial ridicule, attempts to fight back, and the broader culture that maintained and supported the actions. Beginning in the 1950s and 1960s high schools took part in this culture, largely passing it on in the 1960s to George Mason College. The 1970s represent an interesting decade where challenges to the culture of racial ridicule – on behalf of private citizens, students and the federal government – caused a new shift to the school administration at GMC/GMU. Yet, these attempted ameliorations are juxtaposed by outbursts of racial ridicule throughout the decade. Finally, the 1980s and early 1990s represent a resurgent period where a seemingly revanchist culture of racial ridicule rose up, culminating in the 1991 Sigma Chi Blackface incident which held broad implications for the culture of racial ridicule in both society and in institutions.

[1] “Section 53-37 - Ridicule on Account of Creed, Religion, Color, Denomination, Nationality or Race,” Pub. L. No. Conn. Gen. Stat. § 53-37, § Chapter 939 Offenses Against the Person, Title 53, https://www.cga.ct.gov/current/pub/chap_939.htm#sec_53-37.

[2] Patricia Hill Collins, “Controlling Images,” in 50 Concepts for a Critical Phenomenology, ed. Gail Weiss, Ann V. Murphy, and Gayle Salamon (Northwestern University Press, 2019), 77-78.

[3] Ky Buckner, “Racial Ridicule at George Mason · Black Lives Next Door · Legacies,” Black Lives Next Door: George Mason & Northern Virginia In an Age of Disparity & Opportunity, n.d., https://research.centerformasonslegacies.com/s/blnd/page/racial-ridicule-at-george-mason. See notes 9 and 10 – “Mr. Ugly” given to a student of color, and the caricaturized image of indigenous people.