1960s into 1970s: George Mason and Racial Ridicule

Social habits, and traditions of racial ridicule underline the culture of Northern Virginia’s educational institutions throughout the 1950s and 1960s. As shown this culture followed students from high schools into the burgeoning George Mason College. Focusing on the institution of George Mason itself, it becomes apparent that by the end of the1960s these actions had become quotidian, or common enough to become tradition. By the late 1960s the auction or fundraising slave sale, or “Slave Day” was now “an annual institution at the Fairfax college.”[1]

Like the vast majority of these types of events from the previous decade and a half (or longer), students used this event as a fundraiser for a school club – in this case for the college’s Pep Club.[2] Much like those events of the past two decades, the attendance is also demonstrably white too. This can be deduced by the fact that the college’s racial makeup was a majority white, and only now working to integrate students of color into student bodies – much like the regions primary and secondary schools. While the events of racial ridicule had become quotidian, a change in perspective and a change in the institution comes with the turn of the decade.

Racial ridicule did not disappear from the university, however, a recognition of implicit whiteness, racial discrimination, and repression of faculty and student voices from the older and white school administration drove outcry. Both students, faculty, and some of the local community led this charge for change. The change began with upheaval, and a wave of protests in 1970, leading to small institutional changes continuing throughout the decade.

Upheaval in the institution began with the resignation of the Math department’s Dr. Joerg Mayer.[3] Claims from professors over repression, and failure to notify teachers of why they were being fired or not receiving raises by the school’s top administration had driven Mayer to resign. At the same time, other professors and faculty decried being fired or having new contracts rejected by the college, with one student stating “faculty members at this school are afraid to speak their minds because they don’t have tenure and have seen what happened to those who speak out and don’t have tenure.”[4] Included in this group of fired professors was assistant professor William Pei Wei Tsow. Tsow had been teaching Asian studies courses since the late 1960s.[5] Though Chancellor Thompson claimed the professor and their Asian studies courses were dropped for budgetary reasons, students later rebutted that “after the Asian studies courses were dropped…several other history courses were added for the next year and a new instructor hired.”[6]

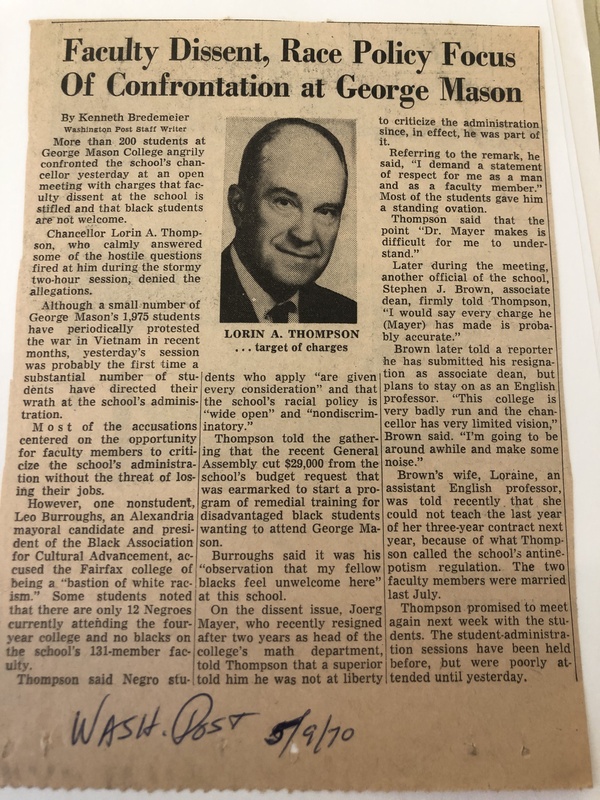

With this uproar, students began to voice their concerns and distaste for the College’s choices – one such concern being the racial disparities in the student body. Chancellor Lorin A. Thompson faced significant protest from the students, with more than 200 students confronting the chancellor at an open meeting on May 1970. The Washington Post noted that while small protests had periodically arisen over the Vietnam War, this protest was “probably the first time a substantial number of students have directed their wrath at the school’s administration.”[7]

Discussions over racial disparities in recruitment, failure to recruit Black and Brown faculty, and unequal treatment play a significant part in these protests. Leo Burroughs, an Alexandria mayoral candidate and president of the Black Association for Cultural Advancement, went so far as to accuse GMC of being a “‘bastion of white racism’.”[8] This is likely due to the distinct lack of Black students at the college, with it being reported as only having 12 (five of which Chancellor Lorin stated are foreign students from Nigeria)[9]* out of a student population of 1,975.[10] Yet, Burroughs’ claims are further bolstered by the fact that out of 131 faculty members, none were Black.[11] Admission standards and student recruitment further implicated the university’s racial inequalities.

Following a faculty vote of confidence to endorse his administration split 60-43 in favor of Thompson, students held a vote expressing no confidence, split 469-129 – though this had no power beyond the expression of student opinion. Two weeks after the initial protest students forced a sit in, driving the chancellor to move the students to a lecture hall for a meeting. There he noted that things would begin to change, and that some of their demands were being investigated.

One such demand included an admission requirement that had forced a Black student to turn in three letters of recommendations while white students expressed that they had never needed to turn in any with their enrollment request.[12] The Alexandria Gazette also noted in their report on the sit in and subsequent meeting that “Thompson indicated he would do what he could to meet at least one of the protestors’ demands – abolish the policy of requiring a small snapshot with each student application.”[13] While the practice of required snapshots was eventually ended, the implication of selection bias by the college is clear. Black students were left under-recruited, with barriers to entry such as extra steps in the form of recommenders, and potentially discriminated against due to the necessity to attach a photograph with application documents. The GMC student body seemed to be aware of these practices, which contrasts the culture of the region and the college at large, which had so far been shown to accept whiteness as a hegemon and permit racial ridicule.

Though the fervor died down with the end of the spring semester, things would start to ramp up again towards the end of 1970, and into the new year. An investigation by the citizen run Fairfax County Council on Human Relations, and later the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare shocked the university, officially calling out the university for the same race based actions brought forward by the students in May 1970. While the Fairfax County Council on Human Relations’ charges brought in January 1971 did not bring significant action due to being unaffiliated with the count, the US Department of Health, Education and Welfare’s (HEW) official report in April 1971 forced the college’s hand.

Charging six different violations of the 1963 Civil Rights Act by discriminating against minority groups, the HEW report stated that “Undeniably, George Mason College has the public image of a ‘white institution’.”[14] The report also declared that the college had not sought to recruit Black students or Black faculty “’in a manner comparable to that conducted to recruit’ white students and faculty.”[15] In public meetings and an official press release following the release of the HEW report, Chancellor Thompson responded with vague statements regarding recruitment of minorities. This included statements that the college “take[s] them all as they come,”[16] or that they followed University of Virginia recruitment policies – that is, no recruitment.

Chancellor Thompson’s claims were challenged by university employees. Karen Wheeler, recently appointed to a college recruitment team at the college stated the no-recruiting policy was news to her.[17] HEW marked its report with a final scathing note, “George Mason College was “conceived of, by, and for the white community of Northern Virginia.” [18] Further reading on this topic can be found in Anthony Guidone’s analysis of Chancellor Thompson, GMC’s administration, the state government, and HEWs encounters during late 1970 and 1971, and US Commission on Civil Rights discussions of racial homogeneity at the college as early as 1963.[19]

[1] “Want to Buy a Slave?” (George Mason University Office of University Relations Newsclippings and Press Releases, November 5, 1968), Series 2: Mixed Materials Box 152, Press Releases, Folder 2, R0004: George Mason University Office of University Relations newsclippings and press releases records 1953-2002.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Thomas Crosby, “George Mason Faculty Shifts Revive Repression Charge,” Washington Star, May 9, 1970.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “OBITUARIES,” The Washington Post, July 21, 1992, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1992/07/21/obituaries/6a130e69-ef0b-4fe7-a022-2eb52f262718/.

[6] Rolf Rykken, “Student Concerns Voiced,” Northern Virginia Sun, May 9, 1970.

[7] Kenneth Bredemeir, “Faculty Dissent, Race Policy Focus of Confrontation at George Mason,” The Washington Post, May 9, 1970.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “Thomas Crosby, “George Mason Faculty Shifts Revive Repression Charge,” Washington Star, May 9, 1970.

*[In Crosby 1970 stated as 12 students including the Nigerian foreign students; In Rykken 1970 stated as 7 Black students – excluding the Nigerian students from the total.]

[10] “Faculty, Students Split in George Mason Votes,” Washington Star, May 24, 1970.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] “College Students Peacefully Protest,” Alexandria Gazette, May 23, 1970.

[14] Kenneth Bredemeir, “HEW Charges Bias At College in Fairfax,” The Washington Post, April 10, 1971.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Charles Cox, “State School Is Charged With Racism,” Richmond Times, April 14, 1971.

[18] Virginia State Advisory Committee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights, George Mason College: For All the People?: A Report of an Investigation (Virginia: US Commission on Civil Rights, 1971), 27.

[19] Anthony Guidone, “The Mission of the College · Black Lives Next Door · Legacies,” Black Lives Next Door: George Mason & Northern Virginia In an Age of Disparity & Opportunity, https://research.centerformasonslegacies.com/s/blnd/page/themissionofthecollege; Anthony Guidone, “The Final Four · Black Lives Next Door · Legacies,” Black Lives Next Door: George Mason & Northern Virginia In an Age of Disparity & Opportunity, https://research.centerformasonslegacies.com/s/blnd/page/thefinalfour.