Holy Integrated

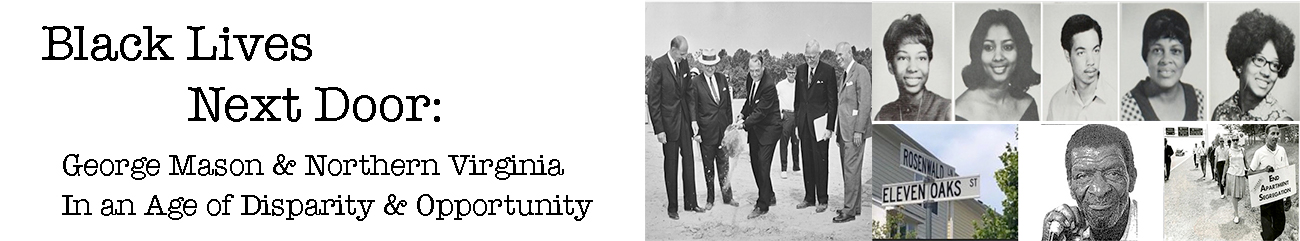

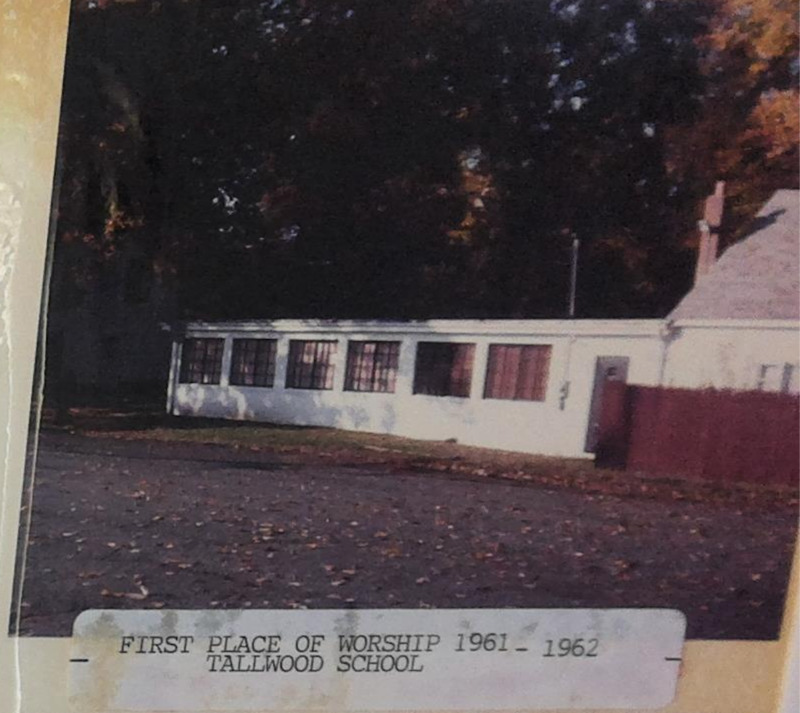

Having just organized in 1961, St. George’s United Methodist Church was a young church finding its place in Fairfax and the Virginia Conference of Methodist churches. Shortly after the founding of George Mason College (1957), they were created to serve new suburban areas in the growing Northern Virginia area and to create a more open and inclusive community. The church’s naming was intentional as St. George was martyred after being executed as Roman officer for refusing to denounce his faith despite the persecution and torture he faced. The founders of St. George’s liked this biblical tale to taking a stand on contemporary issues of civil rights.[i]

As the founding congregation of St. George’s considered their next steps and the purchase of a more permanent location, their pastor, Reverend Carl Ennis and Donald C. Adams of the Payne Street Congregation began discussing the possibility of uniting as one.

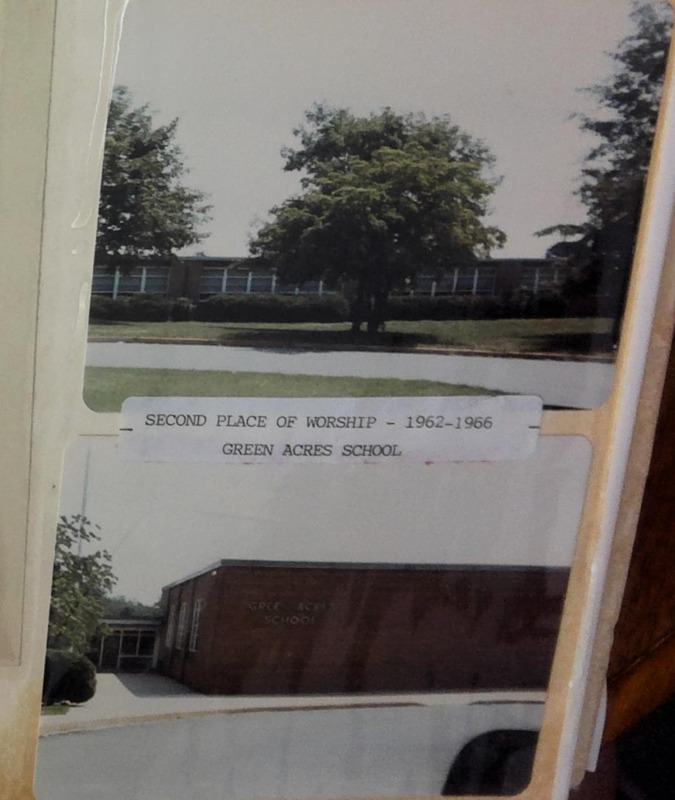

In 1965, St. George’s bought a tract of land off Roberts Road to build a permanent structure and in the same year Payne Street Methodist Church declared their fundraising efforts a failure and voted to disband so that they may join together with St. George’s United Methodist Church. The Payne Street lot was sold and in 1966, when St. George’s had completed the new church off Roberts Road, 9 of the 17 remaining “regular” Payne Street Church members joined them there. Those 9 members donated to St. George’s, their portion of the money earned in the sale of the Payne Street lot, which provided crucial funding for the future success of the church.

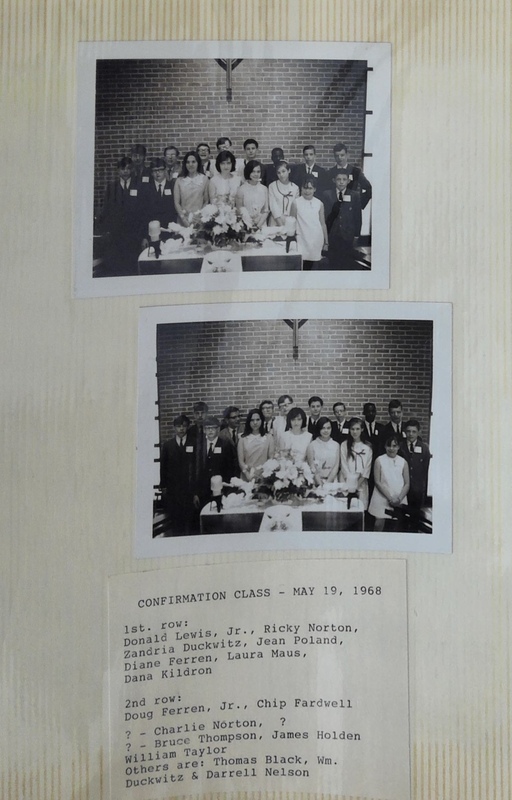

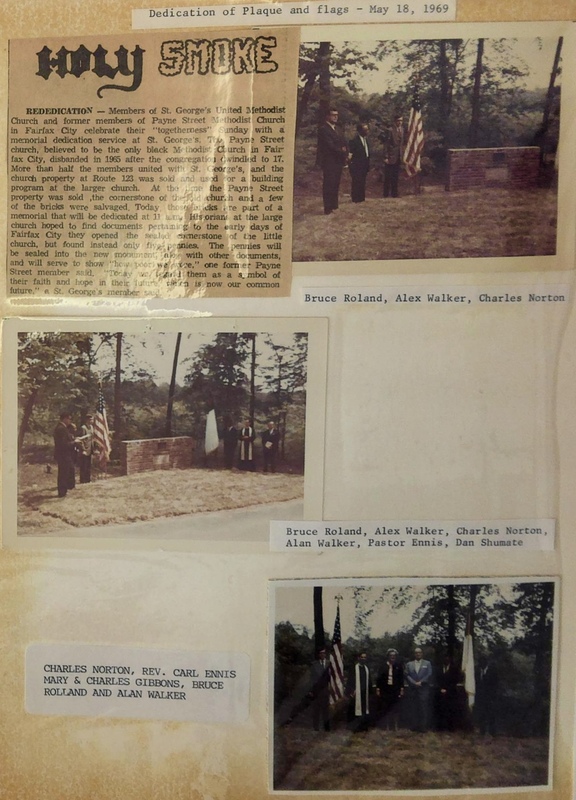

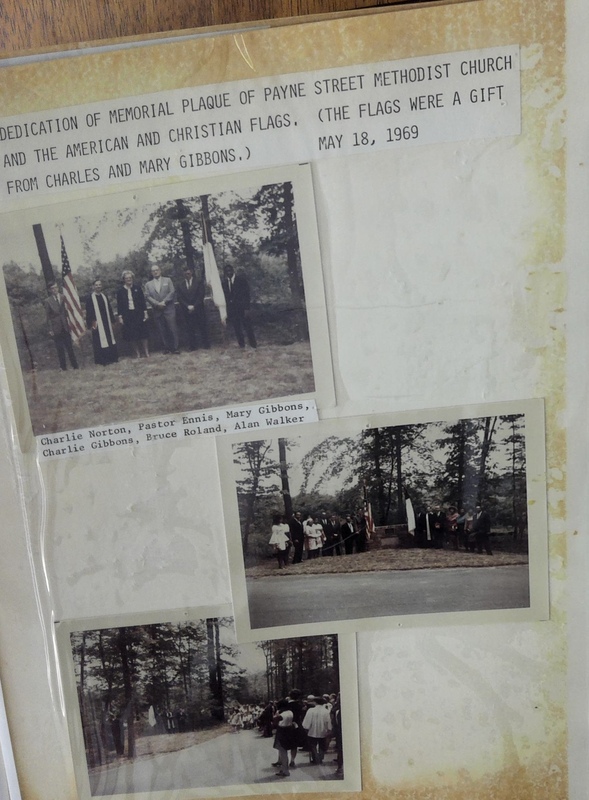

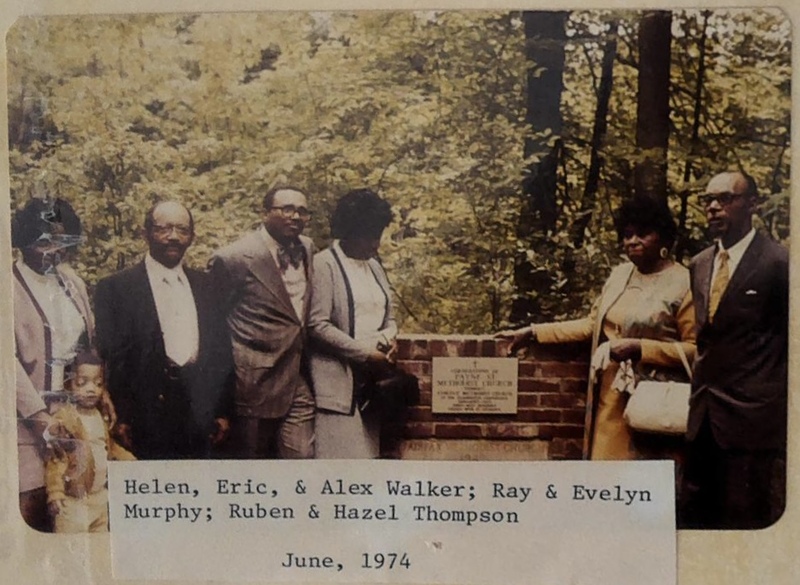

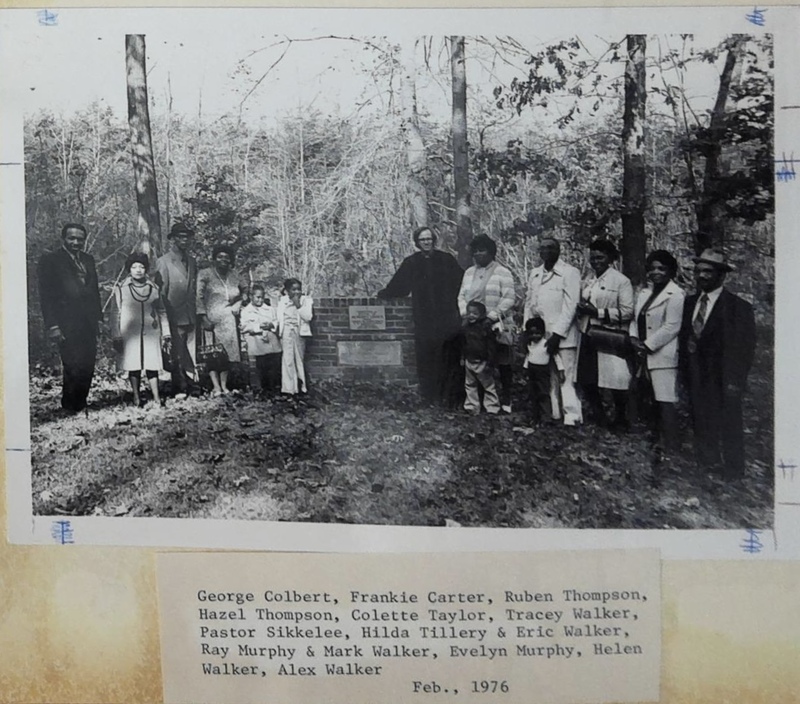

Both parties agreed there should be a landmark memorializing the history of the Payne Street Congregation so Alex Walker and Ruben Thompson, 2 of the 9 who united with St. George’s, salvaged the cornerstone from the Payne Street lot in order to open it and rededicate it as part of their new church. Inside, they found only 5 pennies. One Payne Street member remarked that they were a “symbol of how poor [they] were.” [FN] In May of 1968, an official site was approved for the installation of such a memorial. When it was constructed the congregants decided to fill the new copper container with 2 of the original pennies and some documents telling their history.

The official ceremony was held on May 18, 1969. The Christian and American flags were presented, a plaque was unveiled above the cornerstone, and a historical sketch was given as part of the official proceedings. In late 1972, burglars stole every piece of potentially valuable metal they could from the St. George’s Methodist Church site and that included the memorial plaque. It was promptly replaced with a new designation made of metal they determined as less likely to be stolen.

Nearing a decade since St. George’s and Payne Street’s Integration, the church had certainly grown, but was not able to keep up with other churches. Many solutions were mulled over, but the one everyone overwhelmingly approved of was a relocation to a much busier site close to the intersection of Route 123 and Braddock Road. It would still be very close to the GMU campus, but would hopefully gain them more attention and eventual membership. In early 1979, the church decided to sell the land and church building, the proceeds of which would partially cover the cost of a new church home. George Mason University had wanted to buy St. George’s property on Roberts Road because of its proximity to the growing campus for quite some time. So at the very first opportunity, the school gave them a deal they couldn’t refuse. The GMU Foundation purchased the entire property and agreed to let St. George’s continue to worship there for up to 2 years if necessary while they fundraised and broke ground for their new location. From that point on, the church building was never torn down, but it was secularized and integrated into the university grounds. Eventually it was renamed Carow Hall as it remains today.

It is unknown how long the original Payne Street members stayed with St. George’s or for how many generations. And though the geographic site has been repurposed, the legacy of these people remains. Both sides of this pseudo-merger would have also understood that with the decision to integrate in 1966, just two years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, St. George’s was welcoming more Black people into membership than George Mason University had accepted as students on its campus less than a mile away. How daunting must that have been for this congregation of folks whose history stretched back to before the Civil War? That strong lineage was and is miraculously representative of the survival of family and community through racial segregation, two World Wars, economic depression, and chattel slavery. All of which occurred within the same few miles they continued to live for generations. Claiming Black space in this context with such an esteemed and exclusionary university as neighbor and witness makes this act of unity all the more impressive.

In the geography once occupied by these change makers, Carow Hall stands as a silent memorial of interracial religious community and the ever-astounding Black resilience of this group led by their faith to resist oppression.

[i] St. George’s Church History Book.