1950s and 1960s: High Schools and George Mason College

Northern Virginia in the 1950s and the early 1960s was part of massively changing process of building up and creating landscapes, known as suburbanization. The face of Fairfax County during this period was greatly shifting and seeing a massive influx of residents flocking to built-up suburban landscapes and a growing public and private sector on the doorstep of Washington that brought with it an influx of jobs. These new neighborhoods and sections of Northern Virginia were largely inhabited by middle-class and upper-class families.

The influx of these residents significantly changed the demographics of the county. Whereas the region had largely been rural and inhabited by large landowners, and lower- to middle class farmers, the new inhabitants raised the median wage, and the number of professional class workers. Workers who now typically commuted into the DC-Arlington area instead of working in the towns where they resided. However, while the demographics of individuals moving into the region were changing based upon wage and work/class status, their race reflected a largely heterogenous group. White families comprised the majority of these individuals moving in, further solidifying the racial demographics of Northern Virginia as white, with pockets of communities of color interspersed.

Thus, when examining the dominant culture of schools in the 1950s and 1960s to try to understand why a culture of racial ridicule existed, understanding the culture and race of its students is necessary. The dominant culture of these schools reflects that of the dominant culture of the region, a segregated and white-dominated culture. White, middle- and upper-class residents flocked to the suburbs outside DC during this period as noted, and the segregated schools of the region thereby perpetuated the historically segregated, white-dominated, and white supremacist society’s actions and norms.

The culture of this period of suburbanization and expansion which has largely extended to the present day has purported itself as something that sits above the noise and vitriol of white supremacy, cloaking itself in the rhetoric of modernity and enlightened virtues of colorblindness. However, it is clearly not the case; this era in Northern Virginia is marked by the increased visibility and civil awakening to the horrors of de jure segregation, and the emergence of national and local civil rights movements, while being situated in the birth place of Massive Resistance. The region attempted to embody the narrative of modernity, and progress by burying the narrative of white supremacy using actions that were framed in terms of “harmlessly play” – such as making it a fundraiser for churches or dances at schools – mixed with tropes and stereotypes of a “bygone era” even while massive resistance and anti-integration struggles continued in the region. By reframing these activities as “harmless” and turning them into activities for the (mainly white) general public, it thereby creates an implicit acceptance of these activities as “not racist”, or harmless fun through the normality of racial ridicule masked as an activity for all to take part in. When examining the region through this lens it becomes visible in the culture of high schools, and the emerging George Mason College during the late 1950s and into the 1960s.

Slave sales as fundraisers, date auctions, actions of racial ridicule treated as natural and harmless functions or everyday parts of participating in school, and incidents of “rent a slave” auctions represent the tropes and stereotypes reframed into fun events for students to take part in. These practices were not uncommon throughout the region being practiced at high schools, youth groups, boy scout troops, and George Mason College (GMC). These types of activities stem from a history of minstrelsy, and the violent histories of slave sales that occurred throughout the state in the preceding centuries. However, they are repackaged into everyday functions under a guise of harmlessness, banal activity.

As fundraisers, these activities took different forms. While some involved outright blackface, and clearly portrayed actions of replicating Black stereotypes and trivialized violent histories of chains and whips, generally representations of race took the form of costumes implying Blackness.[1] However, most photographs show students simply taking part in the activity without outright racialized representations of race. Typically, when high school slave sales/auctions were reported in newspapers they were released under the “teen” section of the newspapers, by the papers’ “teen correspondent”. This creates a definite link between high schools, teenagers of the region, and the cultural significance of these actions of racial ridicule.

Cases of slave sales and slave auctions occur throughout the 1950s and 1960s throughout the region. The clearest cases, occurring in the 1960s provide ample descriptions of the forms they took, what they were for, and who was involved. A specific subset of these events was Latin or Roman Nights. A March 1959 case at Annandale High School describes the planned events for Latin Night where the dinner would be served by 25 first-year students. Second-year students were allowed to participate in the slave auction, and third- and fourth-year students as “guests of honor” were provided their own personal slaves.[2]

Another example of the Latin/Roman Night slave sale is the May 22, 1960 case held at Bladensburg, Maryland. While this steps outside the boundaries of Northern Virginia, the Washington Evening Star’s coverage notes the immense, and growing popularity of Latin/Roman Nights at regional high schools, listing the previously discussed Annandale Latin Night, along with other regional high schools’ recent participation in the trend.[3] “Western High in the District and Mount Vernon High and Stratford Junior High in nearby Virginia held their first Roman feasts this spring… The banquets also have proved popular at Annandale, Loudoun County High and Washington-Lee High in Virginia...”, each presumably following the tradition of including slave sales as part of the festivities.[4] The Bladensburg event followed suit, “About 200 Latin students dressed as heralds, senators, gladiators, slaves and vestal dancers parade…around white columns made of cardboard… Six to eight ‘citizens are grouped around four-inch high tables laden with grapes, apples and oranges. The groups buy their servant waitress for the night at a slave auction.”[5] These Latin and Roman Nights only represent a certain subsection of slave sales occurring in the region, as most appear to occur as events titled specifically as “slave sales” or “slave auctions”.

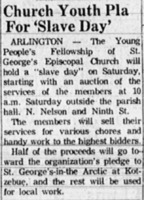

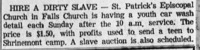

Instances of slave sales occur onward throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s. Taking place as part of church fundraisers and youth groups,[6] as part of United Service Organization gatherings,[7] and at high schools throughout Northern Virginia. These events occur often enough to have become something of a regular practice for students and adults in the region. Which is important to note because during the 1960s it had also become common practice for the students at the growing George Mason College to hold “Slave Day”. The experiences of taking part in slave sales and a culture of parodying violent racial pasts during their time in primary and secondary schooling, at church gatherings, and in youth organizations likely created a culture where this was the norm. Thus, the majority white students of Northern Virginia high schools who were brought up in and took part in this culture brought their previous experiences with them to George Mason College (GMC), along with other colleges and universities throughout the state.

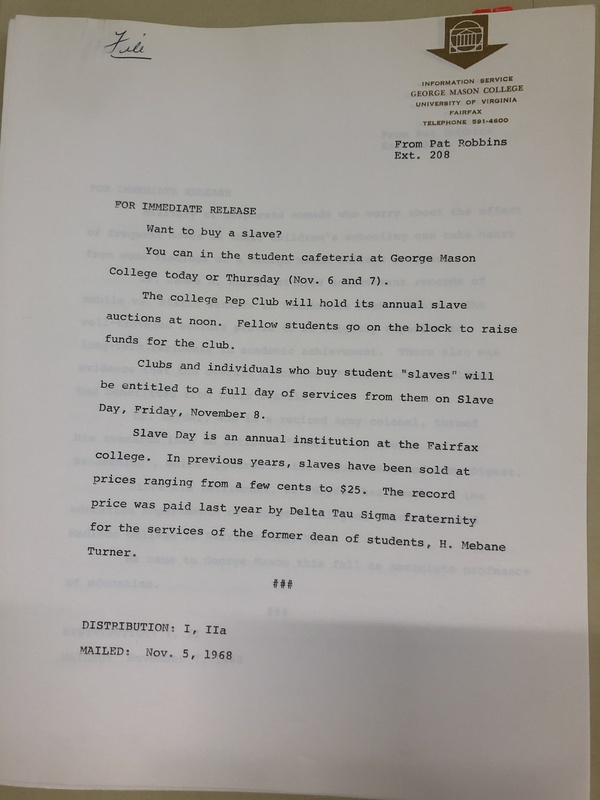

The first known example of a slave sale fundraiser at GMC is the one put on during November 6 and 7, 1968, though it can be deduced that it had been going on for multiple years by this point. In the official school press release from November 5, 1968, the “Slave day” is marketed as an “annual institution” at the college, where “in previous years slaves have been sold at prices ranging from a few cents to $25.” GMC’s slave day also creates an important link between college Greek life and these racist/racialized events both broadly and at GMC.

It is noted in this press release that the previous year’s record sale came from the Delta Tau Sigma fraternity “for the services of the former dean of students, H. Mebane Turner.”[8] The connection with Delta Tau Sigma and racial ridicule runs deeper however. Later colonized by the Kappa Sigma fraternity in 1970,[9] Kappa Sigma’s involvement with a blackface incident in 1985 further implicates Greek life and GMC (later GMU), where a history of racial ridicule, harmful caricatures, and racial exclusion dates back decades to the creation of Greek letter organizations.[10]

The normalization of slave sales as fun events for students to caricaturize racist pasts through the racist present bred a culture of racial ridicule in Northern Virginia. The high schools of Northern Virginia perpetuated whiteness, through the invisibility of and acceptance whiteness as cultural hegemon. The implicit maintenance of a segregated culture, even in nominally desegregated spaces like GMC, is central to this. Bolstered by racialized impressions of Blackness, and caricatures of Black and other Brown cultures – sometimes hidden under monikers of “Latin Night” – racial ridicule became a quotidian practice treated as an activity for whites to enjoy, with no questioning of whether it was okay and who it hurt.

The practices of the predominant culture were then carried over to the newly established and quickly growing George Mason College throughout the late 1950s and into 1960s. Slave sales, Blackface, and racial ridicule underline much of the college culture, creating what fellow CML researcher Ky Buckner titled a “unique minstrel tradition”,[11] and one that remained in Greek life for decades. This is all visible in yearbooks, university press releases, and in the student newspapers. Yet, as the decade ended, recognition of the underlying racial discrimination, disparities in admissions and culture at large appears to shift. The 1970s brings with it a time of unrest and change at George Mason College, later George Mason University in 1972.

[1] Fifi Gorska, “What They Won’t Do For Money,” Washington Evening Star (Washington Star), June 2, 1961, sec. TEEN.

[2] Charlotte Cook, “‘Atoms’ Set Roman Banquet,” Northern Virginia Sun, March 17, 1959, sec. Teen News.

[3] Fifi Gorska, “Even When Not in Rome,” Washington Evening Star, May 22, 1960, sec. TEEN.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “Church Youth Group Pla[n] for ‘Slave Day,’” Northern Virginia Sun, October 4, 1961; “‘Slave Day’ Set by Youth Group,” Northern Virginia Sun, September 8, 1962; “Hire A Dirty Slave,” Northern Virginia Sun, April 25, 1970; “Scouts Post Apology for ‘Slave Sale,’” Washington Post, March 6, 1972.

[7] Nancy Sparks, “USO ‘Isn’t Old Ladies, Doughnuts,’” Northern Virginia Sun, September 11, 1969.

[8] “Want to Buy a Slave?” (George Mason University Office of University Relations Newsclippings and Press Releases, November 5, 1968), Series 2: Mixed Materials Box 152, Press Releases, Folder 2, R0004: George Mason University Office of University Relations newsclippings and press releases records 1953-2002.

[9] Bill Amshey, “Delta Tau Sigma 50th Reunion,” George Mason Alumni Association, 2016, https://alumni.gmu.edu/s/1564/GID2/16/interior.aspx?sid=1564&gid=2&pgid=2290&cid=5246&ecid=5246&crid=0&calpgid=15&calcid=752.

[10] Alfred McClung Lee, Fraternities Without Brotherhood: A Study of Prejudice on the American CampusFraternities Without Brotherhood A Study Of Prejudice On The American Campus - George Mason University Libraries (Beacon Press, 1955; Maggie Holland and Savannah Sicurella | Editor in Chief and Staff Writer, “Confronting UGA’s History of Blackface and Racism on Campus from the Past 70 Years,” The Red and Black, April 4, 2019, https://www.redandblack.com/uganews/confronting-ugas-history-of-blackface-and-racism-on-campus-from-the-past-70-years/article_79d20eda-567f-11e9-bdf2-a3b6b1d7f6ba.html; Joanna S. Hunter and Matthew W. Hughey, “‘It’s Not Written on Their Skin like It Is Ours’: Greek Letter Organizations in the Age of the Multicultural Imperative,” Ethnicities 13, no. 5 (October 1, 2013).

[11] Ky Buckner, “Racial Ridicule at George Mason · Black Lives Next Door · Legacies,” Black Lives Next Door: George Mason & Northern Virginia In an Age of Disparity & Opportunity, n.d., https://research.centerformasonslegacies.com/s/blnd/page/racial-ridicule-at-george-mason.