John B. Ford - Molly Pitts

John B. Ford was an African American landowner who lived in the Mount Vernon district of Fairfax County, Virginia, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This collection of images represents the timeline of John Ford and how he initially became a landowner; this exhibit dives into the lives of the father and grandfather of Ford as there are a multitude of records pertaining to John B. that are missing. It is difficult to gather a comprehensive amount of information on an individual who lived a while ago, however through a couple visits to the Fairfax Archives, the bulk of evidence that has been gathered is through land and tax records.

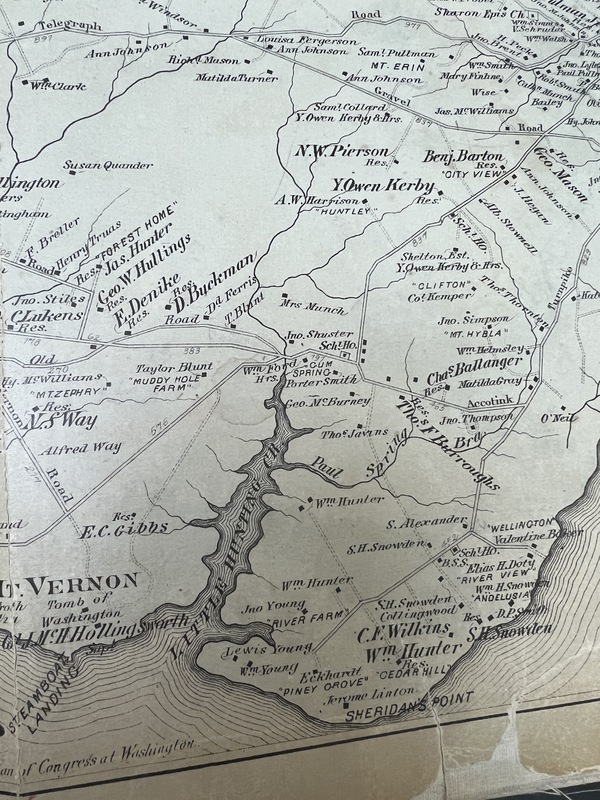

Tracing the history of Black land ownership, we have a solid jumping off point as the records will be available after the Civil War, however throughout the decades there are a variety of “colored” records that hold information on African American landowners. The segregation of black and white people provided more separate documents for each race, however, the racist mentality of those keeping the records prioritizes white information and puts a bigger effort into preserving their records. An advantage given to the Ford family is that they were large and very well known to most of Northern Virginia. Because of West Ford’s popularity, and his savvy business tactics, he was able to have more historical information about him. The Ford family had a long lineage in Virginia and specifically in Gum Springs. He was one of the former slaves who had made it a priority to establish themselves as quickly as possible and create connections with powerful businessmen. In the book Fairfax County, Virginia A History, the origin of black settlement at Gum Springs traces back to West Ford in 1829. He was gifted a tract of land by the General’s nephew, Bushrod Washington, receiving 211 acres. He divided those acres amongst his children, who then subdivided the land to their offspring by 1880. The Archivists said that there was no document they could find showing this transaction, but that it could be relatively misplaced or in some other location.

Where this becomes an issue is for other families and family members. Scholars have argued that all this information being online can help with the cultivation of all the information on these people, mainly through some sort of database like the census. Touching on the census more later, due to the racism during the collection of these documents we are left with some individuals being prioritized over others, leaving holes in the data and frustrating historians.

We did also have a huge advantage over historians during this time, and that’s the internet. Fortunately, my methodology for finding physical copies of documents regarding the Ford family was successful to some extent, any holes within the information could be addressed through the use of census searching on the internet (ex. Ancestry). Simultaneously this works as a translator of sorts; given that many documents were hand-written, it can be difficult to read stretched, cursive writing. Search engines that are dedicated to providing us context, clarification, and a majority of the familial or marital connections were made through archives that we were able to obtain. Due to it not being common during this time to either issue or keep the birth records for individuals, specifically black people, there aren’t any birth records for William Ford or his children readily available.

John B. Ford had seven children with his wife Charlotte. Continuing the pattern before, they had divided up their land to the remaining children in the area before the parents passed. Due to African Americans essentially gaining an identity (in the government’s eyes) after the civil war, there was a tremendous amount of repetition; repetition of names in particular, meaning multiple generations being named the same names. Most African American people lived in close proximity to one another, at least in Virgina, but soon after many of them moved away. A significant amount of evidence and records could be obtained one year, but then the next it almost appears as if people vanished. This was because they moved states, and therefore would not be in state records anymore.