The Gray and Perrow Commissions

The Gray Commission

On July 18, 1955, a federal court ordered the Prince Edward County school board to “make a prompt and reasonable start toward full compliance” with the U.S. Supreme Court’s mandate in Brown.[8] Once the lower court ordered the initiation of desegregation in Virginia’s public schools, the Commission on Public Education, established by Governor Stanley the previous year, began finalizing its recommendations for legislative action. This commission was known as the Gray Commission after its chairman, state Senator Garland Gray. Fenwick was one of thirty-two Virginia legislators appointed to this commission. The legal adviser for the commission, David J. Mays, noted in his diary, that Fenwick was one of several “level-headed” and “stalwart” members of the commission who served as a “stabilizing influence” against more radical proposals.[9]

The commission delivered its final report and unanimous recommendations to the governor on November 11, 1955. It recommended a compromise that would allow for “voluntary” desegregation of individual public schools, while preserving segregation generally. School boards would be authorized to assign individual pupils to specific public schools using criteria that were ostensibly not based on race. Pupil assignment decisions were to be made for “the welfare of the particular child” as well as “the welfare and best interests of all other pupils attending a particular school.” Factors, such as the availability of facilities and transportation, health, a child’s aptitude, as well as vague psychological and sociological criteria were to be considered.[10] Assigning students as individuals rather than as a member of a racial class facilitated continued segregation for plausible reasons other than race. Affected students would find it difficult to prove otherwise.

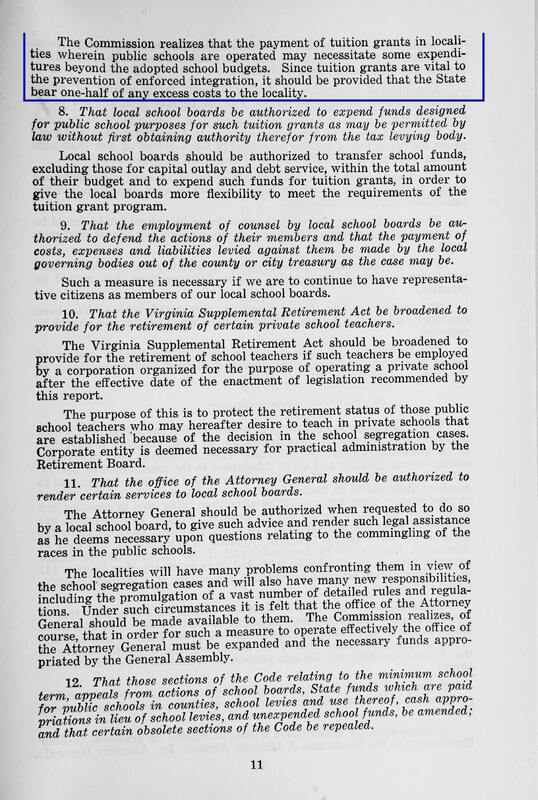

No child would be “required to attend and integrated school.” Parents who chose to send their child to a private school rather than to a “mixed school” could apply for reimbursement of tuition and transportation costs. Local school boards would be required to budget for these tuition grants and collect taxes for this purpose. The state would also reimburse local authorities for up to one-half of tuition grant expenditures that exceeded their budget projections and allowed teachers employed by a corporation operating a private school to qualify for benefits under the Virginia Supplemental Retirement Act.[11]

Opposing “Massive Resistance”

Although the Gray Commission’s legislative proposals would not require a child to attend an integrated public school, they also did not require children to attend a segregated public school. Members of the commission anticipated that public school integration would occur in some localities. The commission’s plan was designed to avert “enforced integration,” not all integration. As lawsuits against Virginia school boards proliferated in the wake of Brown II and federal judges began to order the integration of public schools, opponents of desegregation—led by Byrd and his allies—began to coalesce around the notion of “massive resistance” instead of the Gray Commission’s recommendations. Virginius Dabney, the Pulitzer Prize winner and editor of the Richmond Times-Dispatch, recalls that Byrd apparently did not anticipate the commission’s more moderate recommendation “because he hit the ceiling when he found out about it and made everybody that he could control turn right around and turn somersaults.”[12]

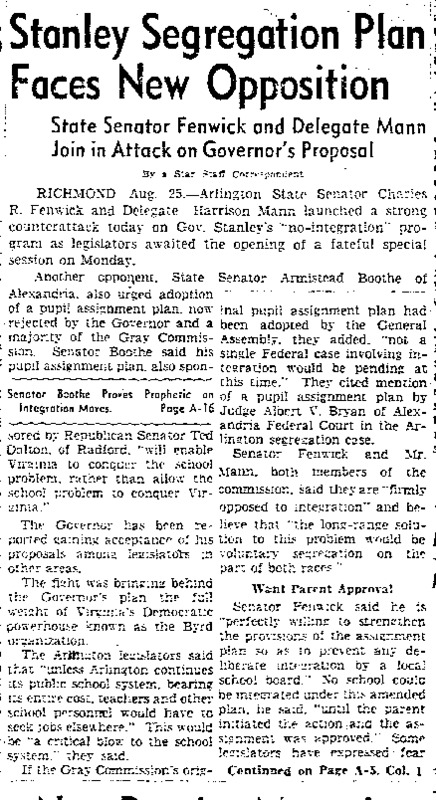

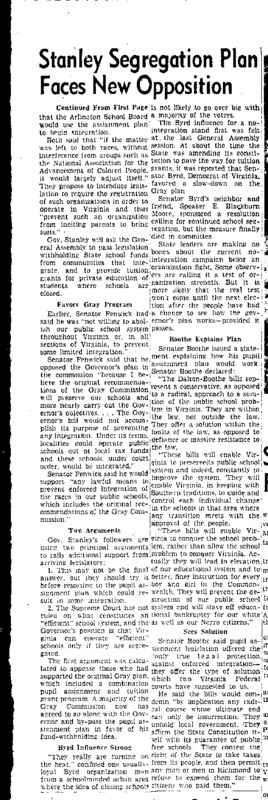

Following a state-wide referendum and a constitutional convention in early 1956 to amend the state constitution and authorize the use of public funds for private nonsectarian school tuition grants, Governor Stanley put forward legislation that disregarded other elements of the commission’s recommendations. Governor Stanley’s plan included provisions that would withhold state funds for public schools from localities that operated even a single integrated school. Moreover, pupil assignment decisions were to be centralized at the state level, in part, to prevent local authorities from voluntarily integrating public schools.

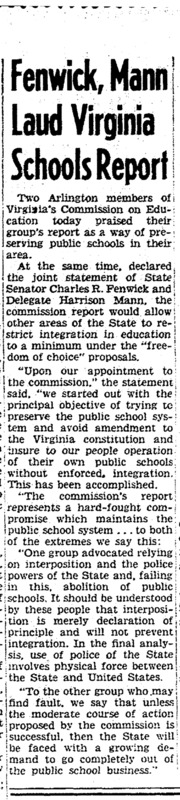

Fenwick opposed Governor Stanley’s plan, leading the opposition in the Senate despite having learned of his brother’s unexpected death earlier in the day. He fought to restore a modified version of the pupil placement plan and proposed legislation that would preserve state funding for public schools—even in districts with integrated schools—if cities and counties adopted the modified pupil placement plan. However, Fenwick’s amendments to the legislation promoted by Governor Stanley were rejected by a vote of 21 to 17 in the Senate.[13] As the fragile consensus achieved by the Gray Commission broke down, a majority of the now divided commission endorsed Governor Stanley’s measures, which the General Assembly enacted in the Appropriations Acts for 1956 and 1958.[14] Much of the Stanley plan, including the closing of schools, would be invalidated by federal and Virginia courts as unconstitutional.[15]

The Perrow Commission

In January 1959, following reverses in state and federal courts and the initiation of lawsuits brought by white parents demanding the reopening of schools, Governor J. Lindsay Almond appointed Fenwick to another Commission on Education—known as Perrow Commission after its chairman, state Senator Mosby Perrow. This commission resurrected many of the original Gray Commission’s recommendations endorsing “local” pupil assignment plans and tuition grants promoting “freedom of choice.” But its recommendations also included provisions that would authorize “cities and counties to cut off local school funds and reduce their school systems to a token operation,” which were to be financed by limited state appropriations.[16] Accepting token integration while attempting to preserve segregation generally, the Perrow Commission’s recommendations were enacted into law in 1959. In the ensuing years many of these statutes were also invalidated as unconstitutional by the courts.[17]

From the beginning Fenwick advocated for a strategy based on locally administered pupil placement plans to effect “voluntary segregation,” and avoid “enforced integration,” in part because he believed such plans were more defensible in court. This assessment was informed by several contemporaneous rulings in various federal courts. For example, in 1955, during proceedings in the South Carolina case of Briggs v. Elliott before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, Judge John J. Parker—who originally upheld racial segregation in Briggs before it was appealed to the Supreme Court and consolidated with Brown—noted that “[n]othing in the Constitution or in the decision of the Supreme Court takes away from the people the freedom to choose the schools they attend. The Constitution, in other words, does not require integration. It merely forbids discrimination. It does not forbid such segregation as occurs as the result of voluntary action. It merely forbids the use of governmental power to enforce segregation.”[18] In a North Carolina case, Carson v. Warlick, pupil placement plans like the one proposed by the Gray Commission, and later the Perrow Commission, were being upheld if children were assigned to a particular school based on individual assessments, not because they were members of a particular racial class. Furthermore, the intricate appeal procedures associated with pupil placement plans also meant that individuals were normally barred from seeking redress from the courts until they had exhausted their appeal rights and other administrative remedies.[19]

As late as 1967, when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down New Kent County Virginia’s “freedom of choice” plans that allowed pupils to choose between attending the predominately white New Kent school and the predominantly black George W. Watkins school, the Court did not say “freedom of choice” plans were unconstitutional. Rather, it held that the “freedom of choice” plans, as implemented, had been ineffective at achieving the mandate in Brown “to effectuate a transition to a racially nondiscriminatory school system” by taking “whatever steps might be necessary to convert to a unitary system in which racial discrimination would be eliminated root and branch.”[20] In other words, “freedom of choice” plans were a practicable first step, but not the only step mandated by Brown and its progeny.

[8] Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, 149 F. Supp. 431, 432 (E.D. Va. 1957).

[9] Sweeney, ed., Race, Reason, and Massive Resistance, 62.

[10] Gray Commission, Public Education Report of the Commission to the Governor of Virginia 8-9 (1955). Mark Golub, “Remembering Massive Resistance to School Desegregation,” Law and History Review 31, no. 3 (2013), 506. Golub notes that this moderate approach is modeled on a North Carolina strategy that “allowed for the highly visible integration of a handful of black students,” while continuing to segregate “more than 98% of the state’s non-white students.” Ibid. J. Rupert Picott, “The Status of Educational Desegregation in Virginia,” Journal of Negro Education 25 (1956) 346. George Lewis, Massive Resistance: The White Response to the Civil Rights Movement (London: Hodder Arnold, 2006), 8. Robbins L. Gates, The Making of Massive Resistance: Virginia's Politics of Public School Desegregation, 1954-1956 (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1964), 66.

[11] Gray Commission, 9-11.

[12] Oral History Interview with Virginius Dabney, July 31, 1975. Interview A-0311-2. Southern Oral History Program Collection (#4007) in the Southern Oral History Program Collection, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Daugherity, Keep On Keeping On, 49 (litigation was initiated against the school boards of Newport News, Norfolk, Charlottesville, and Arlington, and litigation against Prince Edward County was resumed).

[13] Senate Journal, Virginia. Extra Session 1956 (Richmond, 1956), September 21, 1956, 108-113. “Virginia in Turmoil,” The Washington Post, August 29, 1956, 10. Preston, “Assembly Gets New Assigning Plan for Pupils,” 1. Robert E. Baker, “Virginia Assembly Faces 3 Different School Plans,” The Washington Post, August 28, 1956, 21. Robert E. Baker, “Integration Battle Opens on Monday,” The Washington Post, August 26, 1956, 1. Gates, Making of Massive Resistance, 123.

[14] “Stanley Plan Enacted in Virginia,” The Washington Post, September 22, 1956, 1. Douglas Smith, “When Reason Collides with Prejudice: Armistead Booth and the Politics of Desegregation in Virginia,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 102, no. 1 (1994), 30 and 34. Charles H. Ford & Jeffrey L. Littlejohn, “Reconstructing the Old Dominion: Lewis F. Powell, Stuart T. Saunders, and the Virginia Industrialization Group, 1958–65,” Va. Mag. Hist. & Biography 121 (2013), 147–48.

[15] Harrison v. Day, 200 Va. 439 (1959); James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331 (1959); NAACP v. Harrison, 202 Va. 142 (1960).

[16] Perrow Commission, Education In Virginia Report of the Commission on Education to the Governor of Virginia 6, 12, and 14 (1959). “Perrow Program Approval, Minority Battle Expected,” The Evening Star, April 3, 1959, B-2. Tony Stein, “Almond is Defendant in White Parents’ Suit to Open School Doors,” Norfolk Ledger-Dispatch, October 27, 1958, 1. George M. Cochran, “Virginia Facing Reality: The 1959 Perrow Commission,” Augusta Historical Bulletin 42 (Staunton, Virginia: Augusta County Historical Society, 2006), 4. James H. Hershman, Jr., “Massive Resistance Meets Its Match: The Emergence of a Pro-Public School Majority,” in Matthew D. Lassiter & Andrew B. Lewis, eds., The Moderates’ Dilemma: Massive Resistance to School Desegregation in Virginia (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998), 104. Ronald L Heinemann, John G. Kolp, Anthony Parent, Jr., and William G. Shade, Old Dominion, New Commonwealth: A History of Virginia, 1607-2007 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008), 347-48.

[17] Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964). Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430. Daugherity, Keep On Keeping On, 86.

[18] Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776, 777 (E.D.S.C. 1955). “Virginia Session to Hear Stanley Plan Foes Today,” A-27. Luther A. Huston, “Deadline Avoided on Desegregation in South Carolina,” New York Times, July 16, 1955, 1. Sweeney, ed., Race, Reason, and Massive Resistance, 107, n.3. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit exercises jurisdiction over cases arising in Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina.

[19] Carson v. Warlick, 238 F.2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956), cert. denied, 353 U.S. 910 (1957). Hood v. Board of Trustees, 232 F.2d 626 (4th Cir.), cert. denied, 352 U.S. 870 (1956). “Constitutional Law: Segregation. Pupil Assignment. Exhaustion of Pupil Assignment Law Remedies Unnecessary in Fifth Circuit, Required in Eighth, if Local Segregation Policy Exists,” Virginia Law Review, 46, no. 2 (1960), 338. Daniel J. Meador, “The Constitution and the Assignment of Pupils to Public Schools,” Virginia Law Review, 45, no. 4 (1959), 556, n. 187.

[20] Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 435 and 438.