1940s and 1950s: Northern Virginia in the era of Suburbanization and Massive Resistance

The story of the creation of modern – post World War II – Fairfax County is often told through the lens of developers and the private sector, where progress, suburban growth and the expansion of the military industrial complex and economic enterprise of the 20th Century are lauded as supreme achievements. These stories often point to the white landed gentry and rural farmers as resistant to the modern era of suburbanization and post-war boom, and the communities of color in Northern Virginia (mostly small interspersed Black communities) are rarely acknowledged as relevant characters.

“The private sector built it and ‘they’ [emphasis mine] came—scores upon scores of large and smaller employers, top-notch medical professionals, distinguished professors and other teachers, multicultural students, and skilled graduates. They came for the high-paying jobs in modern industries, superior public schools, great housing stock, numerous open spaces, and superb medical facilities.”[1]

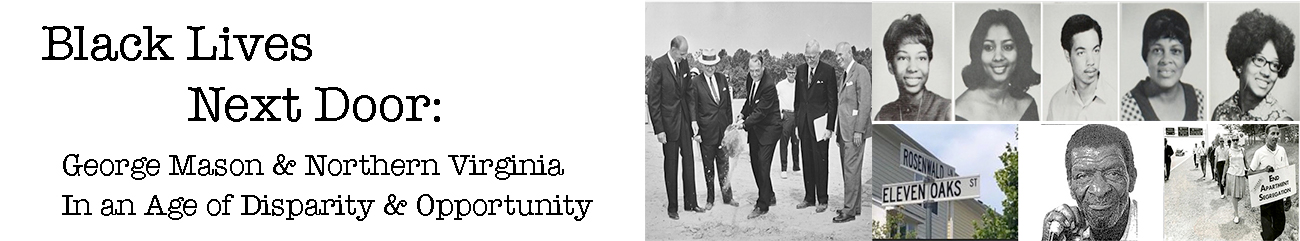

This paints a picture of the post-war era as a progressive, forward-looking region, free from the strife and troubles of the early 1950s, and 1960s. Yet, Northern Virginia was not free from segregation, the removal of Black communities by way of suburbanization, and the latent racism that already existed in the region over 200 years of enslavement, Civil War, and post-Reconstruction Jim Crow. In the words of CML researchers, George Oberle and Benedict Carton, “The transformation of farms and fields into bedroom communities made Fairfax a site of white prosperity and Black displacement.”[2] Their work in Bulldozer is invaluable to understanding the changing face of Northern Virginia during this period.

The post-war epoch in Northern Virginia left not just a scar on the landscape but also in its education system. The legacy of slavery, racism, and the longevity of Jim Crow in Virginia lies at the root of many of the inequitable and unequal changes that came to Northern Virginia. In the years following Brown v. Board of Education’s ruling on desegregating schools, Massive Resistance became the face of Virginia education and this legacy becomes apparent.

Massive Resistance was the post-Brown effort led by Virginia Senator Harry F. Byrd to reject and resist all efforts to integrate schools. Through the passage of laws in 1956, Massive Resistance sought to shut down and defund schools who complied with the Supreme Court’s decision for desegregation “with all deliberate speed”. While court intervention attempted to speed up the process of integration and tear down Massive Resistance’s barriers, the efforts of Massive Resistance remained effective in abating the process of integration. Massive Resistance and its vestiges remained as part of Virginia law until the 1970s, leaving behind a lasting imprint on Virginia’s education system.

Surrounded by the vast systemic and institutionally racist changes (or lack thereof in the case of school integration) in the landscape, the establishment of George Mason College in late 1957 and its new campus breaking ground in 1963 situates the school in a liminal space. College Director, John Norville Gibson Finley noted that while the college was not segregated, the school did not in fact “exert the same effort to recruit [Black] high school seniors that we exert in the recruitment of white students.”[3] Meaning that in its formative years the school was all white, and giving only lip service to inclusivity.[4] George Mason College’s location in the heart of Northern Virginia meant its student body and incoming classes would have grown up in the landscape of new inequalities of suburbanization, and the daily norms of segregation whether by law or through willful obstinance in recruitment at George Mason College in its early years.

Thus, while the school was not segregated, it reflected its surroundings in the post-war era – harboring institutional structures that were averse to inclusion and equality for decades to come. These surroundings and structures created a society that welcomed and hardly challenged racial ridicule for the next four decades.

[1] Russ Banham, The Fight for Fairfax: A Struggle for a Great American County, 2nd ed. (Fairfax, Virginia: GMU Press, 2020), xi.

[2] George Oberle and Benedict Carton, “Bulldozers, Black Lives, White Suburbs: Removing Earth and Memory · Black Lives Next Door · Legacies,” Black Lives Next Door: George Mason & Northern Virginia In an Age of Disparity & Opportunity, https://research.centerformasonslegacies.com/s/blnd/page/bulldozers.

[3] “Correspondence on United States Commission on Civil Rights on Race - Related Admission Policies - Related Documents” (George Mason University Office of the President, 1964 1963), Series 2: Early History, 1949-1967, Box 2, Folder 19, R0019: George Mason University Office of the President records, 1 and 5.

[4] Ibid., 2-4; Anthony Guidone, “For The Mission or ‘For All The People?’ George Mason College’s Response to Civil Rights Investigations · Black Lives Next Door · Legacies,” Black Lives Next Door: George Mason & Northern Virginia In an Age of Disparity & Opportunity, https://research.centerformasonslegacies.com/s/blnd/page/forthemissionorforallthepeople.