Mason, Cold War Positionality, and Blackness in Higher Education

In the post-war period and the burgeoning Cold War, Northern Virginia experienced incredible expansion. The growing and ever-changing region would see a massive influx of primarily white families and professional upper- and middle-class workers, as well as the subjects of the Cold War - imperial subjects, refugees, dignitaries, allies, and foreign nationals. Over the span of a few decades the topography of the region changed from primarily rural farmland dotted with small communities into a sprawling suburb/exurb of the nation’s capital, often displacing the area’s original residents both white and Black. Meanwhile the families and workers coming into Northern Virginia were heavily involved in the Cold War goals and mindset of American exceptionalism and empire, guided by the State Department, national security interest, the military industrial complex, and public and private powerbrokers.

With these new arrivals, Northern Virginia emerged during the Cold War as something Andrew Friedman calls the “Covert Capital,” where the geography of American empire abroad reproduced itself at home “in architecture and spatial relations, and how that home front, in turn, incubated the empire.”[1] The landscape was formed around the growth of the state department and the post-war government, with expansive offices for the CIA and Pentagon in Mclean and Arlington, and the employees who staffed these buildings in both Northern Virginia and Washington residing in the planned communities and suburbs that surrounded them. While the expanding population was primarily white, middle-class workers, the covert capital’s suburban landscape also harbored its imperial subjects and its intimates: immigrants, war refugees, and foreign dignitaries alike. This new population was combined in a space “that was cast as a sign of welcome diversity but also a threat, a dual status that guided rights, benefits, and privileges within preexisting relationships” for those subjects and intimates.[2]

Yet, this same duality had already existed for some of Northern Virginia’s citizens, it’s Black population. Where diversity was shown and espoused for the benefit of the bourgeoning planned community of new Virginia residents, exclusion and restriction for historically Black communities, and their Black residents was abundantly clear. Centuries of denied equality persisted, built a landscape of denial. Cognitive dissonance, and constructed nostalgic "forgetfulness" of the locations racist past underly the predominately white-led development of Northern Virginia and the covert capital.[3] This period was marked by Massive Resistance, de jure and de facto forms of segregation, in addition to removal of Black communities for suburban landscapes to fuel the covert capital. While white residents "continued to see local black and white relationships as merely based on 'mutual respect and admiration,'" hinting at the constructed forgetfulness, Black residents struggled to persist in localities like Fairfax County, where the Black population dropped from 16% in 1940, to 4% in 1970.[4]

The changing demographics and landscape, along with a Cold War ideology, meant the face of Northern Virginia would be changed forever. Part of the changing face of Northern Virginia was its education system. This came in the form of its new flagship college - the then branch of the University of Virginia - George Mason College of the University of Virginia (now George Mason University). With its establishment in late 1957, George Mason College (GMC) was born into the Covert Capital - shaped by Virginia’s racialized history, molded by Cold War ideology and a booming American economy. The heads of the Fairfax community, its local residents, and the administrative powers-that-be at the University of Virginia/GMC shaped the early goals and means of access to the university. Thus, its early student demographics largely represented the historical hierarchies of white hegemony, with little attempt at recruitment or inconspicuous barriers to access for Black and Brown students.

Because of its positionality, GMC was heavily influenced by its surroundings. In an era of great change, struggles over racial equality in the form of Massive Resistance, brought into question the role of George Mason in its community. Was it a segregated school - no,[5] was it a college for all - it claimed to be, yet, who did it seek to educate? While it was never segregated, for its first two to three decades the population of Black and Brown students were incredibly low, calling into question whether they were welcome.

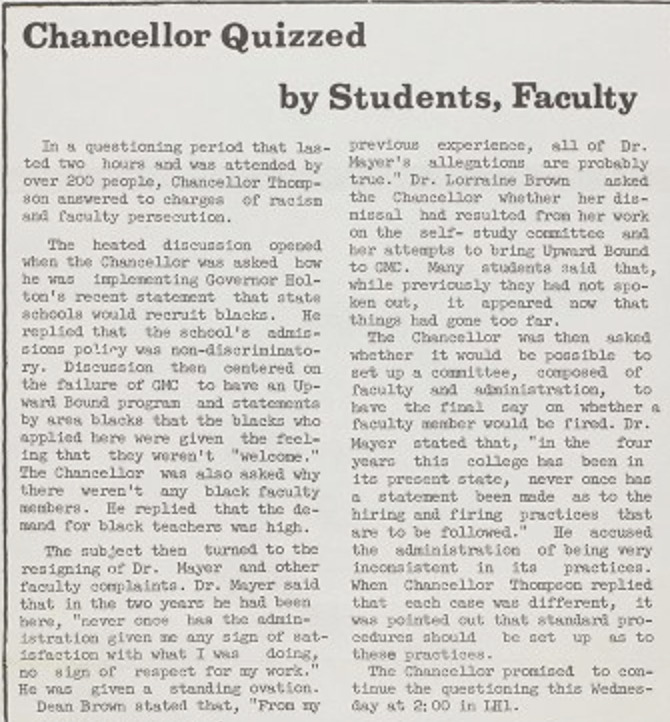

Amid the tumultuous Spring of 1970, student-led strikes and protests against the Vietnam War appeared nationwide. In early May, following the Kent State massacre on May 4th, protest grew more vigorous and even spread to GMC.[6] Coinciding with months of student aggression against firings and non-renewals of professor’s contracts, and faculty repression, protest and came to GMC.[7] This protest was aimed directly at the administration, and the schools Chancellor Lorin A. Thompson took the brunt of the questions at one of his monthly “tea” meetings on May 8th, 1970.[8] This monthly Tea was most likely located in GMC’s library, however reporting suggests this could have been in Lecture Hall. [9] In a flurry of protest and anger, questions were hurled at him by students and local community members. In the mix of questions of academic freedom, and why certain professors had been let go, an interesting and rarely considered set of questions by the student body arose. Why were there so few Black students at GMC? Was GMC recruiting Black students at the same level as white students? And in the case of one of the few Black students, why did they have to attach recommenders to their college application when other white students did not?[10]

In the 1970 academic year while the school’s student body was around 1,900 students, only 12 were Black/African American (5 being Black African exchange students).[11] These Black students also noted in May 1970 gatherings that they felt unwelcome, and uncomfortable on campus.[12] This did not improve over time, stretching into the following decades, even as the Black and Brown population grew on campus.

De facto segregation by administrative negligence or abject lack of interest in the acceptance of local Black and Brown students meant that for those Black students who attended the college/university, their time at the school embodied a fugitive spirit. Thus, Black students at GMU created a pedagogy of escape, resistance, and enlightenment to combat societal and educational structures that impose a narrative of deficits, and discounts Blackness and Black knowledge and pedagogy.[13] They created a fugitive pedagogy by existing on campus, by congregating in its halls, creating Black groups and bringing in Black speakers, or partaking in Black fraternities and sororities. Yet, the nature of deficit ideologies meant that a pedagogy predicated primarily on whiteness remained at GMU, denying a recognized Black pedagogy until the creation of African and African American Studies at GMU in 1992.

The fugitive nature of Black students and Black faculty/administrators on campus who were surrounded by a region that viewed them as deficient, and blamed them for the supposed deficiencies of blackness meant they had to carve out their own place in the school. These students over the decades of George Mason’s growing and changing student body found and built their own spaces in its lecture halls and locations like Student Union Building 1 (SUB1), Finley Hall, and Krug Hall, often times with the help of Black faculty and administrators. CML researchers Shemika Curvey and Rachel Robinson show this in their respective work on fugitive pedagogy and deficit ideologies on campus buildings, mapping the place Black students at George Mason over a very significant period in its history. Their work demonstrates the efforts and successes of Black members of the GMU community over four decades in creating Black pedagogies, curriculums, and communities on campus.

[1]Andrew Friedman, Covert Capital: Landscapes of Denial and the Making of U.S. Empire in the Suburbs of Northern Virginia, American Crossroads 37 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 3.

[2] Ibid, 4.

[3] Ibid, 42-43.

[4] Ibid, 44.

[5] Howard Rogerson to John Finley, November 25, 1963, Office of the President Records, Series 2, Box 2, Folder 19, Special Collections Research Center, University Libraries, George Mason University; John Finley to Howard Rogerson, December 4, 1963, Office of the President Records, Series 2, Box 2, Folder 19, Special Collections Research Center, University Libraries, George Mason University.

[6] Rolf Rykken, “Student Concerns Voiced,” Northern Virginia Sun, May 9, 1970; “Students Have Flag Lowered,” Boradside, May 12, 1970.

[7] “College Students Peacefully Protest,” Alexandria Gazette, May 23, 1970; “Faculty, Students Split in George Mason Votes,” Washington Star, May 24, 1970; “Chancellor Quizzed by Students, Faculty,” Broadside, May 12, 1970.

[8] Thomas Crosby, “George Mason Faculty Shifts Revive Repression Charge,” Washington Star, May 9, 1970.

[9] Invitation to the Chancellor’s Tea, September 24, 1967, Office of the President Records, Series 3, Box 12, Folder 2, Special Collections Research Center, University Libraries, George Mason University.

[10] Kenneth Bredemeir, “Faculty Dissent, Race Policy Focus of Confrontation at George Mason,” The Washington Post, May 9, 1970.

[11] Thomas Crosby, “George Mason Faculty Shifts Revive Repression Charge,” Washington Star, May 9, 1970; Rolf Rykken, “Student Concerns Voiced,” Northern Virginia Sun, May 9, 1970.

*[In Crosby 1970 stated as 12 students including the Nigerian foreign students; In Rykken 1970 stated as 7 Black students – excluding the Nigerian students from the total.]

[12] “Chancellor Quizzed by Students, Faculty,” Broadside, May 12, 1970.

[13] Jarvis R. Givens, Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching (Harvard University Press, 2021), viii and 2.