Bridgett Town: Further Study

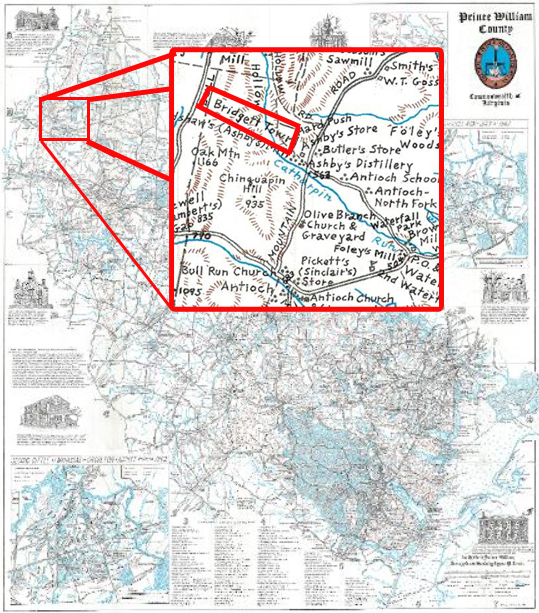

This project started with maps, items designed to reduce space to two dimensions so that it can be defined, labeled, and objectified. In tiny letters, the name Bridgett Town sat snug against the border, the B almost touching the line separating Prince William County from Fauquier County. There were traces of this place in the archive, regularly misspelled and sometimes replaced by other monikers. Bridgett Town Road became Jackson Hollow Road. Bridgett Town became Waterfall, which became Haymarket. The town seemed buried in layers of historical and geographic sediment, but it never completely disappeared. It lived on in the church its namesake James Bridgett helped establish and in the descendants of newly freed African Americans who bought land and built lives just miles from the place of the first battle of the Civil War.

As the demographics of the area changed, those who could, remained. Through Reconstruction, Jim Crow, and Integration, they held onto their land; they fought for agency over their lives; and, although no historical marker draws attention to the place called Bridgett Town, they maintained it in the memories of their descendants, who continue to attend services at the church founded by James Bridgett in 1869 and to tell the stories of playing in the shadow of Bull Run Mountain at night with jars of lightning bugs to illuminate their path.1 In these ways, the Lived Space of Bridgett Town was preserved.

Hostile Nostalgia’s construction of intellectual barriers to protect the dominant culture’s comfortable narrative so as to define a hypothetical space and time is not a terminal state. As shown in this project, Hostile Nostalgia is the systematic protection of a space using various barriers; however, the fact that it was created systematically means that it can be deconstructed systematically as well. The barriers obstructing the public memory of marginalized groups’ experiences can be discovered and disassembled through the exploration of the Lived Spaces, Conceived Spaces, and Perceived Spaces encompassing the space of the past and the present.

Several years ago, the two roads that wind through the Lansdowne property were named in honor of George and Mamie Lansdown, Howard Lansdowne’s parents. This changed the Conceptual Space as it defined the area regarding the family.

Howard Lansdowne discusses the work it took to designate these roads in honor of his parents.

One of the ways that barriers can be felled is to interrogate how black voices have been speaking up against the construction of this nostalgia from the moment of creation2 thereby challenging the Perceived Space and the imaginary past it contains. Esther Washington and Patricia Willis actively pushed against the Hostile Nostalgic narrative put forward by the dominant culture that insisted fallen Confederates were heroes worthy of memorialization and white and black people should not mix. Patricia Willis was able to remove the Confederate iconography from her class ring. Still, it would be decades before the name of Stonewall Jackson High School was changed to Unity Reed High School since the dominant culture continued to maintain that the name was part of its heritage.3 Esther Washington advocated for her students and her children through the tumult of integration, thwarting the agenda of her racist principal, who maintained the nostalgic longing for previously legitimized racial separation. After which, several white residents requested that she teach their children in the upcoming school year.4 By interrogating narratives for silences, the fuller story can be instilled as part of the public memory of this black geography.

The residents interviewed for this project all agreed that their community's history was not well known. The evidence in the archive reveals that the community was known as Bridgett Town at the turn of the 20th century, but as space was redefined, the name was lost, and Waterfall became the designation, then Haymarket. This geographical widening of the definition of place acts as a constructed barrier of Hostile Nostalgia as new definitions of place devour old names and identifications in the Conceived Space.

A Call to Action and a Warning Regarding Further Research

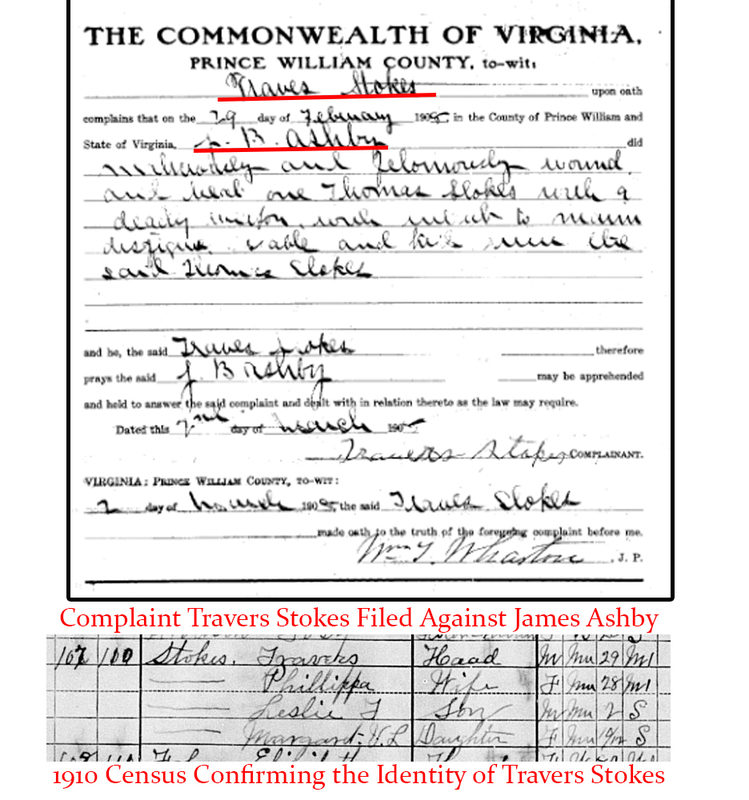

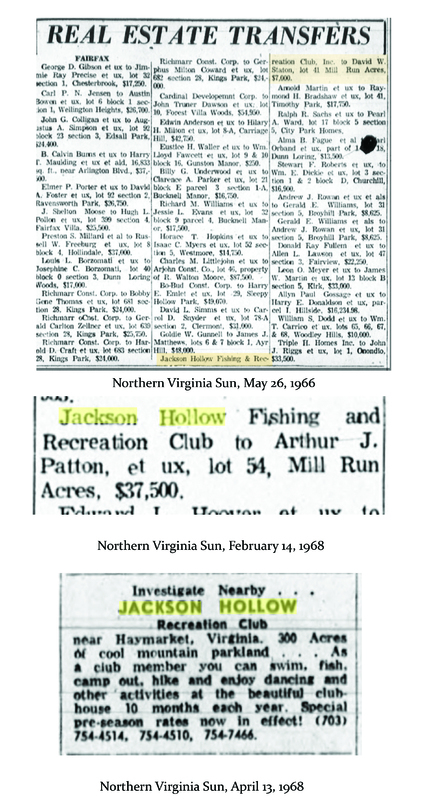

This project represents the beginning of a more extensive exploration of the history of Bridgett Town, as several areas of potential investigation were revealed but were ultimately outside the scope of this particular project. For example, James Ashby, referenced in this project concerning the distillery he operated in Waterfall, appears to have had an unusual relationship with the residents of Bridgett Town. George Hatcher accompanied Ashby to collect fees from sharecroppers and was present when one of these men, Richard Reid, a white man, shot Ashby, paralyzing him.5 There was another black man with Ashby that day, indicating that Ashby had ties with this community. On the other hand, several Bridgett Town residents filed complaints with the Sheriff regarding Ashby’s physical violence against them. These documents challenge the accepted narrative that black residents of the time could not avail themselves of the protection of public safety officials. Was this counter-narrative a result of affinity between the black community and law enforcement, or was it due to animosity between the Sheriff and Ashby? Another potential area of study concerning this black geography involves the Jackson Hollow Recreation and Fishing Club, a segregated facility near Bridgett Town. A dam was built along Catharpin Creek to create a lake for club members to enjoy. How did this affect the Lived Spaces of the residents of Bridgett Town, the geography of which straddled the creek? What about when Hurricane Agnes destroyed the dam in 1972, and the water rushed back down the creek? Furthermore, it seems in the 1960s, the Club started selling off parcels of land. Was this part of the influx of white residents? How did this parcel become the Preserve, “the state-designated Bull Run Mountains Natural Area Preserve”?6 Finally, many more oral histories should be collected to preserve the memories of Bridgett Town.

Finally, the concept of Hostile Nostalgia and the steps necessary to break down its barriers should be tested with other communities or narratives to discover its efficacy. This work can continue to be done with further exploration of Bridgett Town, but it would also benefit from expanding the scope of the project to test this theory on a different population.

by Kristina Nohe

1 Howard Lansdowne, interview by Kristina Nohe, Audio Recording, April 5, 2023.

2 Michel-Rolph Trouillot and Hazel V. Carby, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press, 2015), 52.

3 Emily Sides, “Past Time vs. Too Far: Protests Split on Stonewall Jackson Name Change,” InsideNova, June 25, 2020, https://www.insidenova.com/news/education/prince_william/past-time-vs-too-far-protests-split-on-stonewall-jackson-high-name-change/article_5a6137b8-b332-11ea-8e2a-832003e57cab.html.

4 Esther Washington, interview by Kristina Nohe, Audio Recording, April 21, 2023.

5 “Serious Shooting Affair,” The Manassas Journal, December 15, 1911, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=MO19111215.1.1&srpos=1&e=-------en-20-MO-1-byDA-txt-txIN-%22George+Hatcher%22-------.

6“Field Trip to Bull Run Mountains Natural Area Preserve,” Prince William Wildflower Society, 2021, https://vnps.org/princewilliamwildflowersociety/events/field-trip-to-bull-run-mountains-natural-area-preserve/.