What Does Black Childhood + Menstruation = ?

In Dispossessed Lives, Marisa Fuentes set out to answer various questions about enslaved women encountered in the archive. Two of those questions were of particular importance to me when considering enslaved Black female children who had begun to menstruate. “How did they negotiate physical and sexual violence?” “What do the archival fragments uncover and refuse to reveal about their racial, gendered, and sexual experiences as enslaved subjects?” [1] Knowing enslavers “waited to find out when young, enslaved girls had their first menstrual cycles,”[2] and their “purchases were calculated to ensure a sufficient number of women of breeding age,”[3] how did menstruation further complicate the safety of enslaved black girls?

Encountering Lucy Randolph in the archive was the gut punch that galvanized this entire project. For me, her existence materialized in a Daily Dispatch news article (see image right) that recounted court testimony of her enslaver. At the end of the article it stated, that “she was not quite 15 years of age,”[4] and, immediately struck with deep sadness, I wondered…At such a young age, did Lucy even know she was pregnant? And how might that have informed the birthing outcome? In Birthing a Slave, Marie Schwartz highlights that, “More common that forced pairings [breeding] among slaves were forced sexual encounters between white men and black women. Potential sexual partners [rapists] of enslaved women include the master, his sons, neighboring planters, visitors of the slaveholding family, traveling salesmen, and hired workers.”[5] Therefore, once an enslaved black girl began to menstruate, any safety from racialized-sexual violence afforded by childhood vanished, and the likelihood of impregnation byway of that violence increased exponentially.

Fuentes cautions that the researcher and reader are at risk when “presenting seemingly ‘defeated’ and disfigured subject and presenting ‘too much death’ and violence.”[6] This project endeavors to do no further harm revisiting these events, but here is a warning. Some of the violent details produced by the archive, with respect to Lucy, are included in the following summary. These details lend themselves to questions of the archive and are intended to help magnify Lucy’s humanity, thereby enabling us to truly reconsider her pain.

On 28 August 1852, in Richmond, “not quite 15” Lucy Randolph is accused of infanticide. According to her enslaver’s court testimony, captured in the Daily Dispatch, 9 September 1852, he believed she had given birth and destroyed the child, but apparently did not know she was pregnant. A doctor was called to the premises to evaluate Lucy and found her lying in her room on the floor. He alleges, she denied having given birth, then said she killed it and threw it in the sink. Blood was in the sink, but the infant was found deceased with a headwound in the next yard, covered with straw, and wrapped in an apron. Ann Willis, an enslaved Black woman, testified that Lucy was very unwell that evening and took a considerable amount of medicine, camphor and laudanum, because she was in a lot of pain.[7] Lucy’s medical condition, following giving birth, was also captured in the 2 September Daily Dispatch. (See image left)

Not quite fifteen years old…How did her temporal and spatial geography increase her vulnerability to racialized-sexual violence?

Not quite fifteen years old…How could not knowing she was pregnant have materialized?

Not quite fifteen years old…Still ill five days later, how can we understand her use of medicine?

Not quite fifteen years old…Would she have taken so much medicine if she understood her pain as labor?

Not quite fifteen years old…How might the sheer trauma of laboring/giving birth have impacted her mind?

Not quite fifteen years old…Could the shame of surviving sexual violence have disconnected her from her body? Or from the infant?

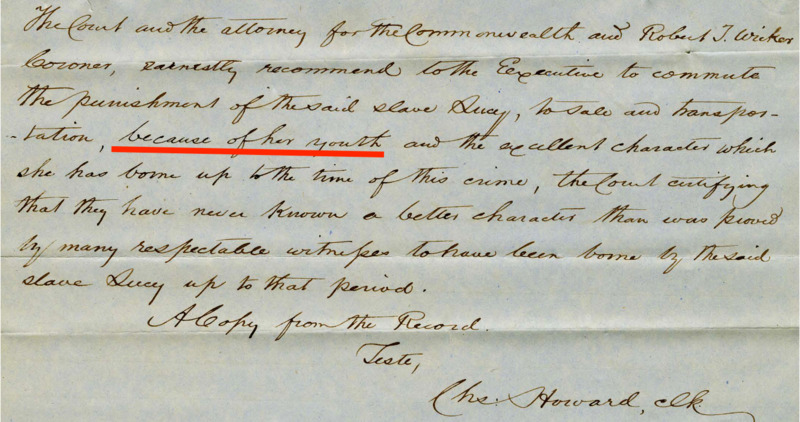

In the four months that followed, Lucy was jailed, convicted, sentenced to death, reprieved, transported to the Virginia penitentiary, and sold. (See story map)

Lucy’s youth was acknowledged by her enslavers, documented in the archive, and cited as the reason for her reprieve. (See above image) However, youth couldn’t shield or spare her from the violences of enslavement. Menstruation equated to commodification. And enslaved Black girls as young as twelve were subjected to racialized-sexual violence for breeding, pleasure, or both.[8] For that reason, it is imperative Lucy’s youth be contextualized alongside her experiences, only then can the complexity of her pain be reconsidered. Utilizing Fuentes’ questions as a framework, when considering how Lucy, who was not quite 15 years old, negotiated physical and sexual violence, all that is knowable is that she survived and the archive refused to reveal her voice. The archival fragments, however, uncover a direct connection from Lucy to young Black girls today who face adultification and the racialized-sexual violence that accompanies it.

[1] Marisa J. Fuentes, “Introduction,” in Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (Univ of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), 3. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1c5chbv.4.

[2] “Race,” The 1619 Project (Hulu, January 26, 2023).

[3] Marie Jenkins Schwartz, “Procreation,” in Birthing a Slave: Motherhood and Medicine in the Antebellum South (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 15.

[4] “Daily Dispatch, Volume 2, Number 270, 9 September 1852,” Daily Dispatch 9 September 1852 - Virginia Chronicle: Digital Newspaper Archive, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=DD18520909.1.2&srpos=44&e=--1852---1852--en-20-DD-41-byDA-txt-txIN-lucy%2Brandolph-------.

[5] Schwartz, “Procreation,” 26.

[6] Marisa J. Fuentes, “Epilogue,” in Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (Univ of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), 146. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1c5chbv.4.

[7] “Daily Dispatch, Volume 2, Number 264, 2 September 1852,” Daily Dispatch 2 September 1852 - Virginia Chronicle: Digital Newspaper Archive, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=DD18520909.1.2&srpos=44&e=--1852---1852--en-20-DD-41-byDA-txt-txIN-lucy%2Brandolph-------

[8] Schwartz, “Procreation,” 23.

By: Shemika Curvey