Instruments of Death or Agency?

In Demonic Grounds, Katherine McKittrick employs the auction block at Green Hill plantation to examine how black femininity intersects with other geographic processes. Though not visible as material spaces or geographies, the wombs of enslaved women also acted as auction blocks for the commodification of their offspring. Like the moment of sale on the auction block, giving birth also “pointed to the continuities of bondage, such as the legally sanctioned captive laboring body, which was always owned and a site of economic transaction.”[1] However, enslaved women's use of abortifacients made their wombs “sites of contestation…and fit into the idea that racial-sexual geographies were alterable sites of struggle.”[2] So were abortifacients “instruments of death” or agency and resistance?

The master narrative presents enslaved Black women as having no knowledge of medicine or medical technology. On the contrary, midwifery and various types of plant medicine were widely shared and understood among them. With respect to fertility, plants like cotton root (see image right), milkweed, Queen Anne’s lace, and parsley were ingested, orally or vaginally, to control menses and/or induce preterm labor. The Journal of the American Herbalists Guild featured an interview with Dave Byrd, formerly enslaved, from the Federal Writers’ Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), who shared the following:

I believe if slavery would have lasted much longer, the Negro race would have depopulated because all of the Negro womens, they had become wise to this here cotton root. They would chew that and they would not give birth to a baby. All of their masters sho’ did have to watch them, but sometimes they would slip out at night and get them a lot of cotton roots and bury them under their quarters.[3]

White enslavers would have to face the contradictions in their ideologies if they acknowledged this method of resistance. Dave Byrd’s interview, however, attests to the knowledge enslaved women possessed and their determination to resist the commodification of their wombs. Moreover, it highlights how the ability to control one’s fertility was vital in environments where racialized-sexual violence was pervasive.

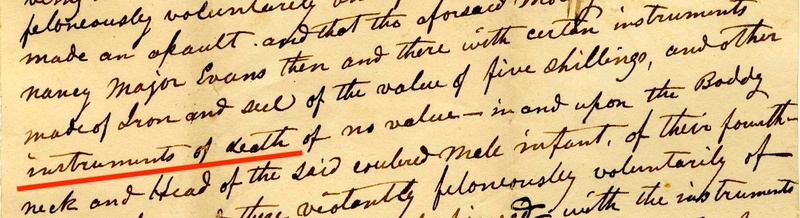

The image above is from Molly’s coroner inquisition in Amherst County, Virginia, 1852, where she is accused of infanticide. Molly, an enslaved Black woman, gave birth to a male infant that perished, and is documented as being accompanied by Nancy Major Evans, a free woman of color. Underlined in red on the inquest are the words “instruments of death” which were allegedly used by Molly and Nancy to carry out the infanticide. We cannot be sure what is being referenced by this phrase, but we can speculate that it may have been abortifacients. In questioning this archival event, how might we reconsider Nancy? Could she have been a local midwife? Medicine woman?

No further documentation could be recovered for Molly, but she wasn’t alone. Like Molly, Lurinda of Patrick County, and Mary of Albemarle County, were also accused of infanticide from use of abortifacients. (See story map) There is one difference however, that should be noted. Lurinda and Mary’s archival incidents occur post-emancipation, and while they are still silenced in a violent archive, the language in the coroner’s inquest is starkly different. I surmise this change occurred because free Black women are not reimbursable.

Regarding language, coroners routinely documented enslaved Black women accused of infanticide as “without god” or “moved by the devil.” This violent archival method is used irrespective of the circumstance surrounding infant death, abortion included. Historically, however, abortion was not a criminal offense but rather a moral one against colonial enslavers’ Christian God. But for enslaved Black women who held on to ancestral practices of spirituality, how might that have informed their use of abortifacients?

In the Journal of Religion in Africa, author Kefas Lamak provided key insights to help reconsider abortion and infanticide through the lens of West African Traditional Religion (WATR). WATR is believed to predate many other world religions and although it varied across the continent, most Africans believed in one supreme being as God. In Yoruba, for instance, the supreme being is Oludumare, who also has emissaries called Orishas (see image left). And to the Yoruba people, the supreme being embodied the beginning and ending of time, space, breath, living beings, and nonliving beings. [4]

Gods, in WATR, were very close to the people and were presumed to communicate with the priests and medicine men. With the abundance of natural resources on the continent, many people possessed unique abilities to use leaves, roots, and branches of trees to make medicines. Therefore, diviners, healers, and priests utilized these abilities to provide their people protection from evil doers.[5] Could this have been Nancy’s role in support of Molly? Could preterm labor be considered protection? Additionally, WATR widely espoused belief in reincarnation, transmigration, and the dead remaining within families, communities, and ethnic groups. Thus, enslaved people who believed in transmigration and reincarnation were more likely to commit suicide to return to their people, as it was better for them to destroy themselves than to remain in service of white enslavers.[6] Therefore, might infanticide also have been viewed as freedom and liberation from bondage?

[1] Katherine McKittrick, “The Authenticity of This Story Has Not Been Documented,” in Demonic Grounds Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 70, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttv711.3.

[2] McKittrick, “The Authenticity of This Story Has Not Been Documented,” 69.

[3] Karen L. Culpepper, “Gossypium Spp. (Cotton Root Bark): A Symbol of Herbal Resistance,” The Journal of the American Herbalists Guild 15, no. 2 (August 2017): 45-52, https://www.americanherbalistsguild.com/sites/americanherbalistsguild.com/files/sample-articles-pdfs/jahg_autumn_2017_cotton_root_culpepper.pdf.

[4] Kefas Lamak, “The Preslavery Praxis and Ethos of the Religion of West African People,” Journal of Religion in Africa, 2022, 6, https://doi.org/10.1163/15700666-12340247.

[5] Lamak, “The Preslavery Praxis,” 12.

[6] Lamak, “The Preslavery Praxis,” 16-17.

By: Shemika Curvey