Excellence in an Age of Neglect

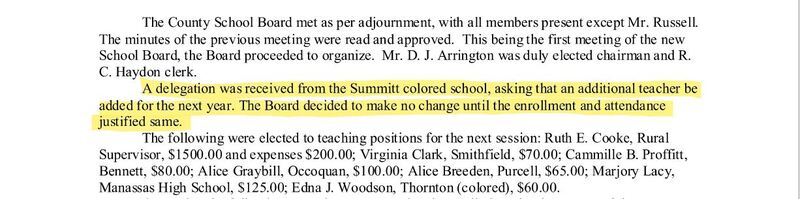

The second era of Summit School was marked by the kind of "drastic fiscal neglect" that was typical of attitudes towards Black schools in the period between Plessy v. Ferguson and Brown v. Board.[1] Somewhat miraculously, by 1924, the two-room schoolhouse had been allotted two personnel by the county: Ernestine P. Grayson as principal and Ella Bailey as primary teacher.[2] Within two years, however, the county had reneged on its initial stance, leaving Grayson as the sole manager of 40 enrolled students.[3] It's likely that this large teacher-to-student ratio negatively impacted the classroom environment for both Grayson and her pupils; by 1928 the county received a request from Summit for the reinstatement of a second teacher. That request was denied, based on the logic that the school's enrollment and attendance did not justify the cost of an additional educator.[4] Five months later, Ernestine Grayson submitted her letter of resignation to the board.[5]

Although school board minutes do not reflect the reason behind Grayson's withdrawal, stories of other teacher departures may provide insight into her decision to leave Summit. In the first decade of the twentieth century, W.C. Taylor, a former Manassas Industrial School principal, resigned from the Brown School due to his "disgust" with the building's inferior condition and the second-class materials that were available to its students.[6] It's possible that Grayson, like Taylor, used her resignation to protest the reduced resources the county had deemed acceptable for her school.

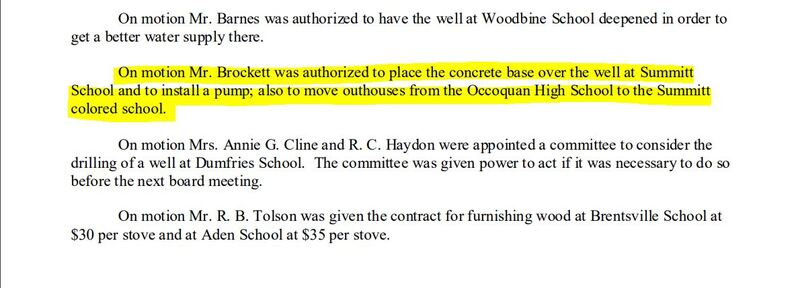

Indeed, most of the equipment provided to Summit came in the form of hand-me-downs from white schools. In 1931, the board authorized the installation of a pump for Summit's well.[7] Over three years later, no progress had been made on the project, except for the declaration that Summit would receive its pump from the shuttered Smithfield School, "if and when it [was] practical to do so."[8] By 1935, the situation had remained unchanged; in a survey of the county's public schools, Superintendent Richard C. Haydon stated that the Black school near Occoquan would see the installation of a pump soon.[9] In this same report, Haydon also listed the school's sparse inventory as including "a few maps, charts, and story books," the number of which was probably insufficient for Summit's 42 enrolled pupils.[10] Even these limited materials were likely castoffs from white schools: in between academic years at Summit, Joyce Webster spent her summer breaks erasing answers from workbooks that had been used by white students the year before.[11] Perhaps the most appalling piece of secondhand equipment Summit received, however, came in the form of outhouses from Occoquan High School.[12] The fact that these toilets came to the school preowned did not seem to have much bearing on the superintendent's assessment of them; Haydon described the school's restroom facilities as "fairly sanitary," failing to provide further elaboration on the outhouses' provenance.[13]

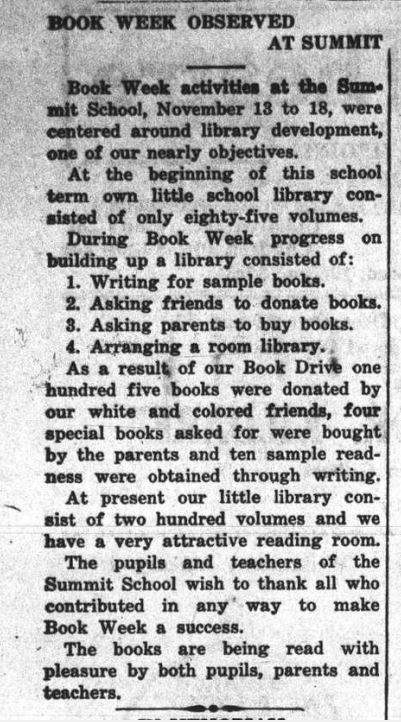

Fortunately, these repeated attempts by the county to limit the success of the Summit School did not take. What was intended to be a site of oppression and injustice against the Black community in Occoquan, instead became a place of self-sufficiency and academic achievement. When Ernestine Grayson submitted her end-of-year summary for the 1926-1927 academic year, she reported that Summit had no library.[14] Twelve years later, the school had managed to acquire nearly 100 books for its students and had established an annual tradition of library development. The efforts of the 1939 Book Week campaign resulted in the donation of 119 materials, more than doubling Summit's library in the span of a few days.[15] Students were expected to utilize this library year-round: during summer breaks, pupils borrowed at least one book in order to complete the required report that was due the following academic session.[16]

This thirst for education also motivated Summit's parent league to advocate for an extension in the school's operation schedule in the spring of 1929. The board declined the request for a one-month addition, stating that existing contracts prevented it from doing so.[17] One year later, the school submitted the same request, this time with a few important qualifiers; parent leagues from both Summit and Kettle Run volunteered to provide half of the financial cost needed to extend the academic term from seven months to eight. The board agreed to this modified proposition, deciding to ask the Rosenwald Fund to cover the remaining expenses.[18] This victory was a significant one in the history of the county's schools: until 1936, most African American schools operated under the seven-month schedule, while white schools followed a nine-month calendar.[19]

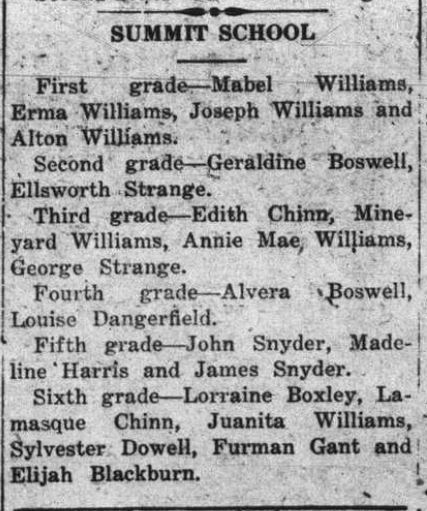

The positive impacts of Summit's extension became apparent almost immediately. In 1932, the Prince William County School system published the honor rolls of 13 of its primary and secondary schools in the Manassas Journal. Summit boasted multiple students in each of its six grade levels, for a grand total of 21. Comparatively, Occoquan High School listed 24 students for the same grade levels – an interesting note to make, since Occoquan likely had a much higher enrollment than Summit.[20] Indeed, for the 1933-1934 school year, Summit had a total enrollment of 42 students. In his 1935 report, Superintendent Haydon casually remarked how "interesting" it was to "find that not any were failed or dropped."[21] Reflecting upon Haydon's findings more than fifty years later, Lucy Phinney described Summit's accomplishment as "remarkable" and "not equaled by any other school in the county."[22] This pattern of excellence continued in 1938 when Summit was listed as the only one-teacher school that achieved a score of 90 out of 100 during the county's "Achievement Day" program.[23]

At the root of Summit's continued success was the prioritization of students' intellectual and physical wellbeing. In 1934, it was discovered that 502 out of 583 Black students had some type of health deficiency in either their eyesight, weight, hearing, or dental health. Although welfare organizations were working to provide in-school lunches to six out of the eleven Black schools in the county, hundreds of students continued to fall through the cracks.[24] The African American community quickly launched a response: in 1938, Black schools presented the board with $140 in donations for the purposes of hosting a dental clinic for their students. The board accepted the request, pairing the substantial amount with $10 from its own reserves.[25] Two years later, students at Summit celebrated the establishment of a lunch program in their school; when Marion Washington began cooking up large batches of soup out of her own home, pupils marveled that Summit no longer "seem[ed] like school, it [was] so home like."[26]

While these moments of charitable giving and fraternity are heartwarming, it is important to remember that the reason they came to pass was because of Prince William County's purposeful dereliction of duty. Time and again, the county claimed insufficient funds for programs that would have benefited African American schools, only to approve nonessential items for white schools, like "more adequate playground[s]."[27] Although both Black and white families paid taxes towards public education, Black communities were required to supply additional funds to ensure their children received an adequate education.[28] The African American community in Occoquan was willing to do whatever it took to secure necessary resources; the drive to accomplish this was so profound that it would lead some members in the community to consider the matter of consolidation, and the eventual closing of Summit.

By Stephanie Martinez

[1] Jerome E. Morris, Benjamin D. Parker, and Luimil M. Negrón, “Black School Closings Aren’t New: Historically Contextualizing Contemporary School Closings and Black Community Resistance,” Educational Researcher 51, no. 9 (2022): pp. 575-583, https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x221131504, 577.

[2] Prince William County School Board, transcribed by Morgan Breeden, Minutes of the Prince William County School Board July 2, 1923 – August 3, 1927, Book 2, https://www.historicprincewilliam.org/county-history/schools/book2.pdf, 27.

[3] Lucy Walsh Phinney, Yesterday's Schools: Public Elementary Education in Prince William County, Virginia, 1869-1969: A Social and Educational History of a Rural County in Virginia (Richmond, VA: R. E. F. Typesetting & Publishing, Incorporated, 1993), 174.

[4] Prince William County School Board, transcribed by Morgan Breeden, Minutes of the Prince William County School Board September 4, 1927 – June 7, 1933, Book 3, https://www.historicprincewilliam.org/county-history/schools/book3.pdf, 28.

[5] Prince William County School Board, Minutes of the Prince William County School Board September 4, 1927 – June 7, 1933, Book 3, 42.

[6] Phinney, 93.

[7] Prince William County School Board, Minutes of the Prince William County School Board September 4, 1927 – June 7, 1933, Book 3, 143.

[8] Prince William County School Board, transcribed by Morgan Breeden, Minutes of the Prince William County School Board July 5, 1933 – June 24, 1939, Book 4, https://www.historicprincewilliam.org/county-history/schools/book4.pdf, 77.

[9] Richard C. Haydon, "An Administrative Study of the Public School System in Prince William County, Virginia," Master's thesis, (University of Virginia, 1935), 103.

[10] Haydon, 102-103.

[11] Marguerite Harris and Joyce Webster, "NVCROH Interview with Marguerite Harris and Joyce Webster (2/6)," by Marion Dobbins, Northern Virginia Civil Rights Archive, November 21, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r03X2TiP280.

[12] Prince William County School Board, Minutes of the Prince William County School Board September 4, 1927 – June 7, 1933, Book 3, 143.

[13] Haydon, 103.

[14] Phinney, 174-175.

[15] "Book Week Observed at Summit," Manassas Journal, December 28, 1939, Virginia Chronicle.

[16] Marguerite Harris and Joyce Webster, "NVCROH Interview with Marguerite Harris and Joyce Webster (4/6)," by Marion Dobbins, Northern Virginia Civil Rights Archive, November 21, 2014, https://youtu.be/FJgOdFgvIPE.

[17] Prince William County School Board, Minutes of the Prince William County School Board September 4, 1927 – June 7, 1933, Book 3, 49.

[18] Prince William County School Board, Minutes of the Prince William County School Board September 4, 1927 – June 7, 1933, Book 3, 91.

[19] Prince William County School Board, Minutes of the Prince William County School Board July 5, 1933 – June 24, 1939, Book 4, 144.

[20] "Honor Roll, Prince William County Schools," Manassas Journal, November 3, 1932, Virginia Chronicle.

[21] Haydon, 102.

[22] Phinney, 175.

[23] "Patrons Pleased by Pupils," Manassas Journal, May 26, 1938, Virginia Chronicle.

[24] Haydon, 111-112.

[25] Prince William County School Board, Minutes of the Prince William County School Board July 5, 1933 – June 24, 1939, Book 4, 270.

[26] "Summit School," Circuit (Catlett, VA), February 2, 1940, Virginia Chronicle.

[27] Prince William County School Board, Minutes of the Prince William County School Board September 4, 1927 – June 7, 1933, Book 3, 51.

[28] Phinney, 39.