Geographies of Exclusion and Agency

When Lewis Henry Bailey first entered the small town of Occoquan, he was determined to create places where members of the local Black community could gather.[1] Passionate about church planting, Reverend Bailey, along with two other trustees, purchased land for the establishment of Ebenezer Baptist in 1881.[2] Approximately 30 years later, the minister, along with Ogle Harris and Reverend John Wesley Jackson, organized the Progressive Lodge of Odd Fellows, No. 6876.[3] Within three years of acquiring land adjacent to the church for this mutual aid society, the "commodious and comfortable" Odd Fellows Hall opened to the local African American community.[4]

Intertwined with his commitment to spiritual and fraternal development, Reverend Bailey also prioritized the pursuit of education. Born into slavery in the first half of the nineteenth century, his aspirations for literacy were denied until after the Civil War. Once emancipated, Bailey traveled on foot from Texas to his home state of Virginia, where he learned to read and write. He quickly enrolled in Wayland Seminary (known today as Virginia Union University) and began to study education and theology.[5] It is likely that these experiences inspired Reverend Bailey to establish the only institution to ever exist exclusively for Black students in the Occoquan region: Summit School.

When Ebenezer Baptist Church was officially organized, the nearest school for African American students who lived in Occoquan was the Brown School, located more than 15 miles away in Manassas.[6] Although the passage of the Virginia Public Education Act in 1870 had mandated a public school system for all children in Virginia, the Prince William County Public School Board had only established three institutions for Black students by 1883.[7] This number stands in stark contrast to the approximately 30 schools organized for white children by the same year.[8] In the Occoquan district, two county-backed schools served white students in the area; no schools were available for the approximately 100 Black families that lived within the Occoquan village or the Black populations in the neighboring communities of Agnewville and Neabsco.[9] The county's decision to unevenly invest in the development of Black institutions is characteristic of school boards managed exclusively by white southerners at the time.[10]

In response to this act of oppression by way of exclusion, Bailey and the African American community in Occoquan created their own place of learning. According to Ebenezer history, Summit School was founded around the same time that the church was first organized, in 1883.[11] While the location of the school in its first few years is unclear, it was not unusual for students and teachers in Prince William County to utilize rooms in local churches if a dedicated building was not available to them.[12] For all intents and purposes, Summit and Ebenezer likely operated as a single institution for the first 10 years of the school's existence. This idea is further supported by the fact that Summit's first recorded teacher was Ella Dean Bailey, Reverend Bailey's wife.[13] Born after the Civil War, Ella was the younger sister of Jennie Dean, founder of the Manassas Industrial School. Like her sister, Mrs. Bailey had a passion for teaching; in between terms at Summit, Ella enrolled in education courses at Virginia Union.[14]

Mrs. Bailey's service to the school continued even when control of Summit passed to the county around the turn of the century. In the fall of 1892, three trustees from the county school board acquired half an acre of land from John M. Carr for "the use of the public schools of the Occoquan school district."[15] Although the deed does not list Summit by name, the parcel's size contains a clue about the district's intentions for the land. According to Lucy Phinney, half acre plots acquired by the county were "barely large enough to hold [a] schoolhouse, well, and privies," never mind superfluous elements like playgrounds; while white schools received expansive allotments, Black schools made do with the limited space they were allowed.[16]

Although the details regarding Summit's transfer to the county are currently unknown, the transition appears to have concluded by the beginning of the twentieth century. A 1901 map indicates the presence of a Black schoolhouse approximately one mile from Ebenezer Baptist Church, outside the town boundaries of Occoquan.[17] It is not clear why the board selected this location for Summit, especially considering the significant overlap that existed between the church and the school. Although no public school for white children existed within the town at the time the map was created, within eight years the county had established a two-room schoolhouse for white students in Occoquan proper.[18]

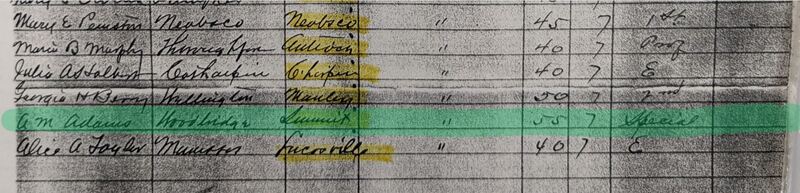

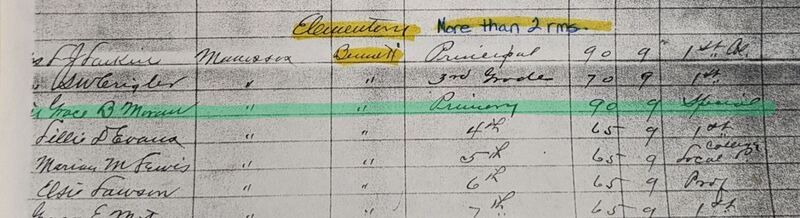

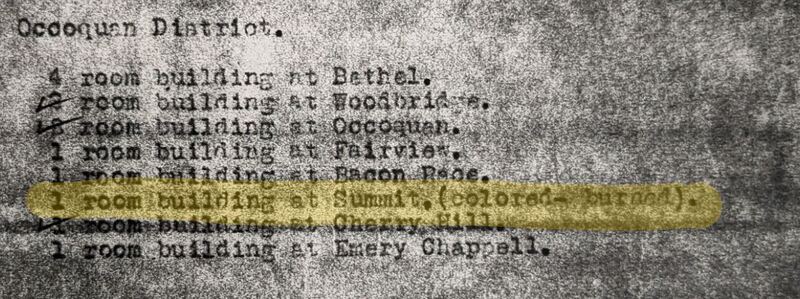

Summit's first building, however, consisted of only one room, making it difficult to accommodate the 107 Black students that lived within the Occoquan district.[19] Despite the potential for high enrollment at the school, it is likely that the board provided Summit with limited funds, making it difficult to hire multiple educators. When Dewitt Bates attended the Cabin Branch School in the 1910s, his teacher was responsible for 75 African American children at any given moment. Individual instruction at the one-room schoolhouse in Batestown was extremely limited: Bates' teacher would tutor a group of students for 30 minutes, assign them independent work, then begin lessons with the next cohort.[20] Unsurprisingly, this grueling workload did not result in higher compensation packages for Black teachers. Educator contracts indicate that A. M. Adams was employed as Summit's only teacher in 1919 at a rate of $55 per month for a seven-month term. Meanwhile, at Bennett Elementary in Manassas, Grace B. Moran was one of nine white educators offered a nine-month contract at a rate of $90 per month. The discrepancy between Adams' and Moran's contracts is heightened by the fact that both educators held identical "special" certificates.[21]

At some point the county likely realized the need for expanded facilities at Summit, because in 1915 the board began to seek bids for the "erection and completion of an addition to the [Black] schoolhouse near Occoquan."[22] Although the notice underscored the necessity for construction to conclude by September of that year, the project was not completed in time. Responding to this need for a meeting space, the African American community in Occoquan quickly offered temporary accommodations in the form of Odd Fellows Hall. Once renovations on the schoolhouse were complete, Summit's students returned to their expanded building.[23] Any excitement the pupils may have felt about their school's upgrades, however, was likely cut short when Summit caught fire in 1918.[24]

Although the cause of the blaze remains unknown, several potential explanations exist. In Prince William County, gas and kerosene lamps were often used to light classrooms on overcast days; the presence of wood burning stoves also exacerbated the risk of fire.[25] While it is possible that the tragedy at Summit was caused by one of these hazards, it is also important to consider the possibility that the blaze was intentionally set. Following the period of Reconstruction, rage at Black progress often manifested in the form of targeted attacks against community churches and schools.[26] According to Joyce Webster's father, white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan occasionally held gatherings in the Occoquan region. Growing up at the beginning of the twentieth century, Mr. Webster worried about encountering these groups after sundown near areas like Hooes Creek Run.[27] Avoiding this part of the county was easy to do at night, but less so during the day: the space where the KKK was said to congregate was approximately one mile from the Summit schoolhouse.

By 1923, a new building for African American pupils had opened at the same location.[28] This rebuilding of the schoolhouse marked one of the final times the district was willing to significantly invest in the Summit community. For 40 years, Black families in the Occoquan region had responded to several types of exclusion at the hands of the county: exclusion from the public school system, from Occoquan proper, and from essential resources needed to adequately serve Summit's teacher and students. In response, the African American community crafted their own geographies of agency, acceptance, and education. As Summit School entered the next stage of its life, the battle to maintain these places of Black resistance would face unprecedented levels of county opposition.

By Stephanie Martinez

[1] Jacqueline Trescott, “The Remembrances of a Pioneer,” Washington Post, December 6, 1987, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1987/12/06/the-remembrances-of-a-pioneer/5abbb4be-9c66-42b1-96e5-1b1db245b14c/.

[2] Prince William County Circuit Court Clerk's Office, "Deed between Henry F. Duty and the New School Baptist Church," June 21, 1881, Deed Book 34, page 46, https://www4.pwcva.gov/Web/document/DOCC4185904?search=DOCSEARCH82S2.

[3] Prince William County Circuit Court Clerk's Office, "Deed between Janie Duty and the Occoquan Progressive Lodge of Odd Fellows, No. 6876," April 22, 1909, Deed Book 59, page 498, https://www4.pwcva.gov/Web/document/DOCC4196860?search=DOCSEARCH82S2.

[4] Julia Mason Layton, “Trip to Occoquan,” Washington Bee, March 18, 1911, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84025891/1911-03-18/ed-1/seq-1/.

[5] Trescott, “The Remembrances of a Pioneer."

[6] Lucy Walsh Phinney, Yesterday's Schools: Public Elementary Education in Prince William County, Virginia, 1869-1969: A Social and Educational History of a Rural County in Virginia (Richmond, VA: R. E. F. Typesetting & Publishing, Incorporated, 1993), 93.

[7] Phinney, 31.

[8] Phinney, 57-58.

[9] Earnie Porta, Images of America: Occoquan (Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2010), 84.

[10] Jerome E. Morris, Benjamin D. Parker, and Luimil M. Negrón, “Black School Closings Aren’t New: Historically Contextualizing Contemporary School Closings and Black Community Resistance,” Educational Researcher 51, no. 9 (2022): pp. 575-583, https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x221131504, 577.

[11] Marguerite Harris and Joyce Webster, "NVCROH Interview with Marguerite Harris and Joyce Webster (3/6)," by Marion Dobbins, Northern Virginia Civil Rights Archive, November 21, 2014, https://youtu.be/bYUTvXtADjo.

[12] Phinney, 31.

[13] Prince William County School Board, transcribed by Morgan Breeden, Minutes of the Prince William County School Board July 2, 1923 – August 3, 1927, Book 2, https://www.historicprincewilliam.org/county-history/schools/book2.pdf, 2.

[14] Harris and Webster, "NVCROH Interview with Marguerite Harris and Joyce Webster (3/6)."

[15] Prince William County Circuit Court Clerk's Office, "Deed between John H. Carr and the Occoquan District School Board," September 28, 1892, Deed Book 42, page 97, https://www4.pwcva.gov/Web/document/DOCC4189261?search=DOCSEARCH82S2.

[16] Phinney, 75.

[17] William H. Brown, Map of Prince William County, Virginia: compiled from U.S. Geological Survey and other data and corrected with the assistance of reliable residents of the county, (Washington, D.C.: A. B. Graham Photo. Lith, 1901). https://www.loc.gov/item/2006700181/.

[18] Phinney, 158.

[19] Brown, Map of Prince William County, Virginia.

[20] Dewitt Bates, "Transcript of Interview with Dewitt Bates: Recollections of Batestown in the Dumfries Magisterial District, Prince William County, Virginia," interview by Tom Nelson, April 4, 1984 (Prince William County Historical Commission Oral History Program), 43-45.

[21] Prince William County School Board, "Report of Teachers Contracted with for Prince William Division, September 15, 1919," Lucy Walsh Phinney Collection, 1991-1993, Prince William Public Libraries (Prince William County, Virginia, 1919).

[22] "Sealed Bids Wanted," Manassas Journal, July 30, 1915, Virginia Chronicle.

[23] Historic Occoquan, Inc., "Transcript of Interview with Historic Occoquan, Inc. (Schools)," interview by Tom Nelson on September 24, 1985 (Prince William County Historical Commission Oral History Project, 1985), 12.

[24] "Brief Local News," Manassas Journal, June 14, 1918, Virginia Chronicle.

[25] Phinney, 31-32.

[26] Morris, Parker, and Negrón, 576.

[27] Marguerite Harris and Joyce Webster, "NVCROH Interview with Marguerite Harris and Joyce Webster (5/6)," by Marion Dobbins, Northern Virginia Civil Rights Archive, November 21, 2014, https://youtu.be/Glxz5M7jhmI.

[28] Prince William County School Board, Minutes of the Prince William County School Board July 2, 1923 – August 3, 1927, Book 2, 8.