Family Tree

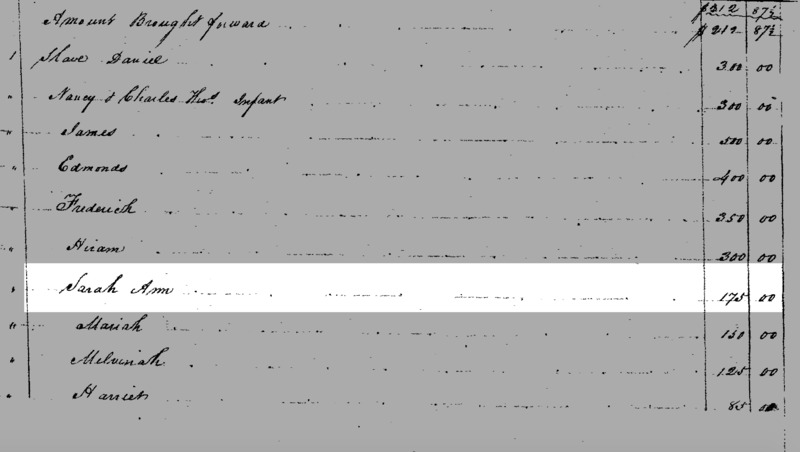

Sarah Ann was born enslaved on the plantation of Nathaniel Barker, Mary Follin’s father. The first record found of her that I’ve been able to find so far is Nathaniel Barker’s will and inventory of property after his death.[i] This inventory and appraisal (see below) occurred in 1834 and though age was not listed, she would have been about six years old. Her value was determined to be $175 which is more than some enslaved people with feminine names who I assumed to be women/girls and less than others, but less than every person with a masculine name. This is due to the gendered nature of value within the institution of slavery. Men and young boys were highly valued for their physical labor and women and young girls were scaled on other measures. Though they were seen as not being able to produce as much through physical farm labor as their male counterparts, enslaved girls became highly valued when they were able to begin giving birth.

Originally, I was going to suppose who among the other enslaved people could have potentially been her parents based on their names and monetary value. I narrowed it down to Daniel, James, Vincent, Nancy, Hannah, and Addison. The first three names were who I assumed to be men in the right age range to be a father based on their names and value, while the last three I assumed to be women who could have been her mother for the same reason. Reading the actual will of Nathaniel Barker (see below), however, clarified and provided more insight to who Sarah Ann’s parents were.[ii] Nathaniel Barker specified that when he died, a few of his sons would be given specific enslaved people that he owned. Son Enoch was given a “boy named Vincent,” and William (also the executor of his father’s will) was given a “young man named Addison.” These statements themselves cleared some assumptions up: Vincent was not a man, but a boy, which could account for his high value, and Addison was not a woman, but a man. Perhaps Addison could be Sarah Ann’s father.

Nathaniel states that all other enslaved people and property are to be given to his wife Letitia until her death. He specifically names “Nancy with her children namely, James, Edmond, Frederick, Hiome (unsure of spelling), Sarah Ann, Maria, Elina, Harriet, and a suckling infant not yet named.” This gives context to the appraisal that was done shortly thereafter. If Addison was a man and all those named above were Nancy’s children, the list of enslaved folks in the inventory was done in family order: First father, then mother, then children. Daniel and Nancy were Sarah Ann’s parents, these were her siblings. With this context, reading the inventory also complicates the naming of Sarah Ann’s future children. Her youngest brother, the “suckling infant not yet named” in the will was given a name before the inventory was taken, and it was Charles. As in Charles William, Sarah Ann’s son born in New York.

The will also stipulated what was to be done after the death of Nathaniel’s wife Letitia. He stated that all property besides what had been willed to his sons previously was to be sold to settle his debts and the leftover money would be split among his children. Before that sale was to take place, however, his son William was to receive even more exempted property: “three boys (the children of Nancy), James, Edmond and Frederick to him and his heirs forever.”

After this final giving, the sale of other property and people commenced. Here, John Follin purchased Hannah and Eliza, from the other enslaved family owned by the Barkers, and William Barker purchased Daniel, Sarah Ann’s dad (See left).[iii] Sarah Ann’s family was officially being split up. Her father and brothers were sold away, and her mother and sisters’ fates were completely in the air. There was a chancery case filed after the sale and split of profits because Mary Follin, the only married Barker girl, was not able to inherit anything due to her status and therefore felt slighted. Since she was a woman, her name is never mentioned in the legal records, but her husband John publicly fought for their inheritance, after purchasing two enslaved women. It was very common to settle debts in private as well as in public and while there is no record of John Follin ever purchasing any of Nancy’s children, including Sarah Ann, he does eventually own them and so it is possible that an exchange was made external of the chancery case.

The next time Sarah Ann shows up in the official record is when John Follin dies. Because he died without a will, an inventory and appraisal of his property was done before deciding the fate of his material possessions. This is almost 10 years later, in 1841, and lists Sarah Ann as being about 16 years old, lining up with the time frame.[iv] At this point, she is worth $400, which is more than “Hannah and child aged 38” who were together appraised for $325. However, “Sarah with child aged 23” were together appraised for $450, and “Sammy and child aged 28” were appraised for $425. Since Sarah Ann was seen as somehow less valuable than these women and their children, her reproductive ability must have been unknown to her enslavers at this point. That said, in order for her to have a daughter around 7 years old in 1850, Sarah Ann on John Follin’s inventory was either about to become pregnant or had not yet realized that she was.

Also significant about this Follin inventory is the reappearance of Harriet, Sarah Ann’s sister. In the right hand column, a Harriet, aged 12 years old, was appraised at $325. Being only two years younger in this record makes sense in conjunction with Nathaniel Barker’s will which lists Harriet three spaces below Sarah Ann and worth less than half the amount of money. It seems that none of Sarah Ann’s other siblings or family members ended up on the Follin Plantation, however. The destruction of her family structure, isolation, and brutal sexualization consistently defined Sarah Ann’s girlhood at the hands of the Barkers and the Follins, the only comfort likely being her sister Harriet’s shared captivity.

[i] “Inventory and Appraisal of Nathaniel Barker’s Property January 1834,” n.d. Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records.

[ii] “Nathaniel Barker Will 1833,” n.d. Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records.

[iii] “Chancery Case after John Follin’s Death. Includes a Copy of Nathaniel Barker’s Will and the Record of Sale between Him and John Follin When Follin Purchased Hannah and Her Daughter Eliza,” n.d. Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records.

[iv] “Inventory of John Follin’s Property in 29 June 1841,” n.d. Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records.