Legacies

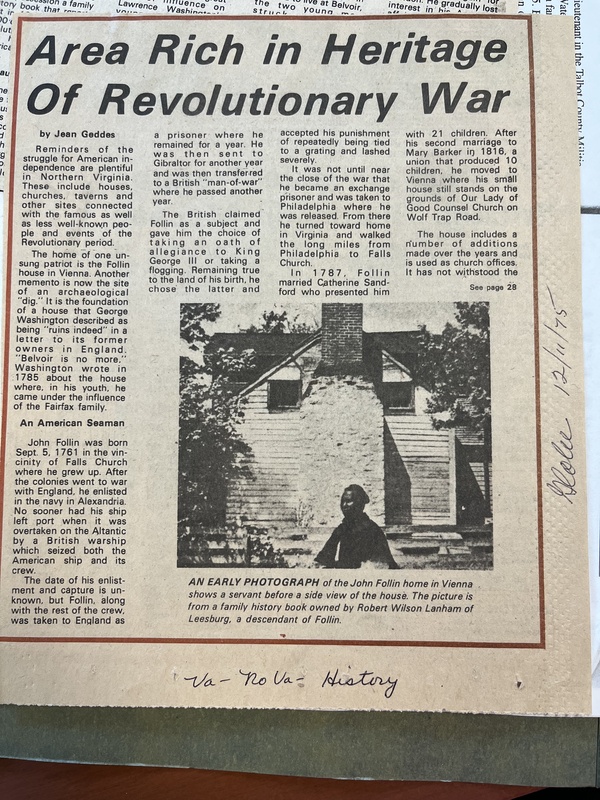

In 1975, the Follins were interviewed for a newspaper article about John Follin’s heroic involvement in the American Revolutionary War. They sang his praises and discussed his military as well as personal achievements that had landed him and both his two wives reinterred at Arlington National Cemetery. The Vienna house he and Mary lived in was described as having been donated to the Our Lady of Good Counsel Catholic Church on Wolf Trap Road and would soon be demolished for renovation. The most interesting thing about this article, however, even more so than the idolization of John Follin, was the photo the family had chosen to submit. This photo is the only photo of the Follin home in the public record and shows a Black woman in the foreground. A Black woman standing in front of a plantation home in the 1800s was put in the newspaper for an article singing the praises of the plantation’s master… in the 70s. As if more damnation was required, the caption of the photo reads:

“An early photograph of the John Follin home in Vienna shows a servant before a side view of the house. The picture is from a family history book.”[i]

In that family history book, it is revealed that the woman in the photo is none other than Harriet Bell, Sarah Ann’s sister. Not a servant by any stretch of the imagination, Harriet was enslaved. Harriet remained on the Follin plantation until Mary Follin died in 1863 and while the book describes her as “devoted to Mrs. Follin” and claims that she “refused freedom rather than desert her,” that could not be farther from the truth.[i] In 1876, when Harriet was finally free and had saved up some money, she bought back 10 acres of the original Follin plantation. In her will, she continued to pass this plot of land down, creating generational wealth and property for her family as the ultimate form of resistance. Black success, particularly Black woman and mother success for her children through the purchasing of property, was an intentional and awe-inspiring reclamation of her story and reclamation of geography which had oppressed her. In 1960, her descendants named a road after her, Bell Lane, which still stands today. Literally, geographically it is facing off with Follin Lane, the road named after the people who enslaved her, Sarah Ann, and so many others. If only their mother Nancy could have seen the inspiring strength and resilience of these two daughters of hers. This strength stemming from Black motherhood allowed them each to create their own family legacies in Nancy’s honor and in direct defiance of the Follin’s legacy of silencing and erasure.

Because Sarah Ann successfully smuggled Mary and Charles out of the South and died shortly thereafter, the children may have never known their family history. They may have never known that their aunt was such a powerful Black woman as well, who was setting up her future generations for success while also deeply missing her sister and wondering where she had gone and if her or her children were still alive. Ultimately, this family was left with separation, a loss of history and a loss of family. It was a strategic loss and necessitated for survival but a loss nonetheless. It echoes the digital project “Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery” which chronicles and maps the thousands of newspaper ads that were put out by formerly enslaved folks after emancipation so that they could hopefully locate lost family members they had been separated from. These ads often provided a last seen location or some kind of family detail. However, in the case of Mary Eliza and Charles William, they likely did not even know where to start looking for their family. The lines connecting them to their past had been severed with the death of their mother.

As this journey of Finding Sarah Ann continues, there are several points of expansion, but most importantly, this project can continue to emphasize the creation of family legacies. There are several obvious families who are uniquely involved and could potentially contribute to the story: the descendants of Mary and Charles William, the Brecks, the Martins, the Darlings, the Barnetts, the Smallwoods, the Osborns, the descendants of Harriet Bell, and of course the Follins. These families might have more information that could help tell the story of Sarah Ann at many different points in her life. It is also possible that the descendants of these families do not have any information to share, that their history was kept secret from them as well. The legacies of fear, oppression, and most of all silence forced these people, apart from the Follins, into the shadows of their everyday lives and into the shadows of history. Perhaps Finding Sarah Ann has just let in the first bit of light.

This story of Sarah Ann navigating the land while being explicitly conceptualized as property herself, literally giving her life for her children, leaving her sister behind and choosing to continue the separation of family in order to herself survive, and fighting tirelessly to gain a control she never had over her own body is chilling and inspiring. Traces are left in the land she walked here in Northern Virginia, though she practically vanished into thin air. Her spirit remains in the branches of her family tree which continues to grow disconnected and in all of the people whose lives she changed through her resilience. It is in the street signs and sidewalks that have tried and failed to cover up a history no one ever thought was important or possible to tell.

And while there are blanks left to be filled and questions left to be answered, Sarah Ann is found.

[i] Geddes, Jean. “Area Rich in Heritage of Revolutionary War,” December 11, 1975. Fairfax County Library, Virginia Room; Edmonston, Gabriel. A Genealogical History of the Follin Family in America. 1128 Twelfth St. N. W., Washington, D.C.: G. Edmonston, 1911.