Questions? Implications?

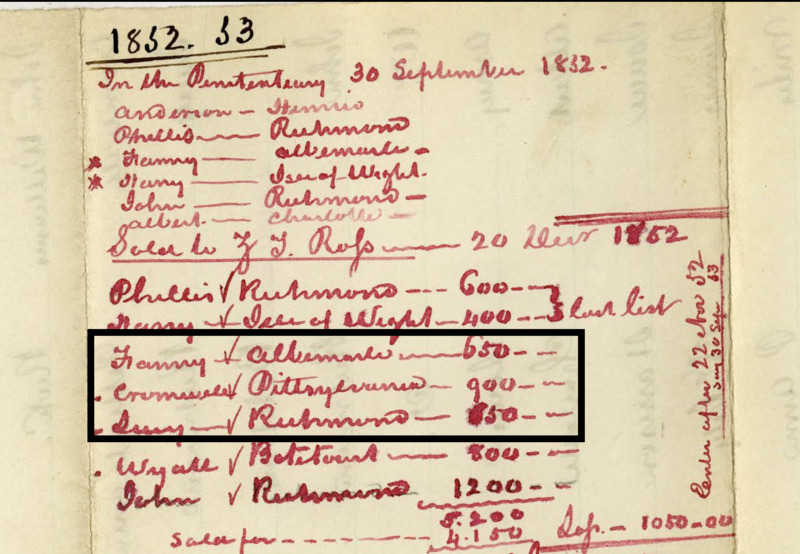

While the penalty for infanticide was death, most enslaved Black women faced social death in lieu of execution. Stripped from their families and communities, they were sold south in groups from the Virginia penitentiary ensuring profit for the state. Most of the women in this project disappeared immediately after encountering them. But, in a chance occurrence, I found “not quite 15” Lucy of Henrico County and Fanny (1852) of Albemarle County, on the same Virginia penitentiary document. Imprisoned together, they were sold south to the same enslaver 20 December 1852. (see image right) Might Fanny and Lucy have interacted? If so, were they any comfort to one another?

Throughout this exhibit, the enslaved Black women I encountered in the archive are mapped to spatialize their negotiations of captivity as it pertained to reproduction. The violent, fragmented glimpses into each enslaved woman’s life left several questions unanswered and rendered their stories incomplete. With the fragments, I attempted to recast them as protagonists to offer an alternate narrative that magnified their humanity. Because as noted by Marisa Fuentes, enslaved women “appear as historical subjects…documented in the manner in which they lived: spectacularly violated, objectified, disposable, hypersexualized and silenced.”[1] And the thirty coroner’s inquisitions used in this project were no exception. These documents proved to be spectacles of inexact pseudo-science, motivated by profit, in a larger system designed to commodify Black bodies. Like justices, coroners “were bound by law and custom to honor the rights of slave owners.”[2] Therefore, the documentation of infanticide was inextricably tied to monetary loss or gain for enslavers, not truth.

This project set out to interrogate the archival narrative surrounding infanticide among enslaved Black women in Virginia. I located approximately thirty women in the archive between the years of 1805 and 1867. During this period, the enslaved population in Virginia grew to roughly 490-thousand souls, the highest of the slaveholding states[3], making the incidents of infanticide among enslaved women extremely rare, .006 percent. This number is even lower when the inaccuracies of the archive are considered. Nevertheless, all occurrences of infanticide were tragic and complex, the burden of which fell on enslaved Black women.

Part of Fuentes’ Black geographic theory is understanding these enslaved women’s stories constitute the “history of our present.”[4] The legacies of slavery continue to plague the American medical establishment with plantation-like medical protocols that dismiss Black pain, silence Black voices, and result in the loss of life. From slavery to the present, Black birth and motherhood has been demonized and pathologized. Consider…

- How the crime of infanticide was easily ascribed to enslaved Black women because as Thomas Jefferson wrote, “it was not the labor, but the increase which was the first consideration.”[5]

- How breeding and forced reproduction morphed into equally sinister methods of commodification like the prison industrial complex.

- How federal and state governments enacted forced sterilization laws linked to public assistance and sterilized Black women more than three times the rate of white women.[6]

- How fetal protection laws were drafted to criminalize poor Black women with limited access to reproductive healthcare.[7]

- How today, the Black maternal mortality rate is three to four times higher than white, even though Black women only make up 15% of births annually.[8]

In Demonic Grounds, Katherine McKittrick states, “Black women’s histories, lives, and spaces must be understood as enmeshing with traditional geographic arrangements in order to identify a different way of knowing and writing the social world and to expand how the production of space is achieved across terrains of domination.”[9] This project endeavored toward that understanding by examining and reconsidering archival records of infanticide among enslaved Black women in Virginia. I cross-referenced coroner’s inquests with old newspapers, scholarly articles, and books to uncover a different way of knowing and writing about these archival women. With them centered, deconstructing the master narrative through questions about abortion/abortifacients, God, menstruation, violence, and compassion brought their resilience and agency into focus. Yet I ended the project with more questions than when I began and came away with few definitive answers.

We will never know their pain…

We will never know their points of view…

We will never know their circumstances…

We will never know their negotiations…

We will never know their truth…

We only know they survived…

It is important for me to share that I was radically affected throughout the process of researching and formulating this project. I became extremely invested in the lives of the enslaved Black women I encountered, and they became a part of me. I would routinely speak their names aloud while searching the archive then listen for their whispers. Without doubt, they shaped this project through small nudges and delicate hints which led me from one document to the next. Therefore, I conclude this project with deep sadness for what they endured but profound respect for how they endured. I consider them ancestors and guides on my journey to create a more equitable and just world, and hope this work honored their existence.

[1] Marisa J. Fuentes, “Introduction,” in Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), 5, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1c5chbv.4.

[2] Philip J. Schwarz, “Slaves and Capital Punishment,” in Slave Laws in Virginia (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010), 79.

[3] Philip D. Morgan and Michael L. Nicholls, “Slaves in Piedmont Virginia, 1720-1790,” The William and Mary Quarterly 46, no. 2 (1989): 211, https://doi.org/10.2307/1920253.

[4] Marisa J. Fuentes, “Epilogue,” in Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), 148, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1c5chbv.10.

[5] Jennifer L. Morgan, “Partus Sequitur Ventrem: Law, Race, and Reproduction in Colonial Slavery,” Small Axe (Duke University Press, April 3, 2018), https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/4/article/689365/pdf.

[6] Alexandra Stern, “Forced Sterilization Policies in the US Targeted Minorities and Those with Disabilities – and Lasted into the 21st Century,” Institute for Healthcare Policy & Innovation, https://ihpi.umich.edu/news/forced-sterilization-policies-us-targeted-minorities-and-those-disabilities-and-lasted-21st.

[7] Dorothy E. Roberts, “Preface,” in Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty (New York: Vintage, 1999).

[8] Donna Hoyert, “Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2020,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, February 23, 2022), https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2020/maternal-mortality-rates-2020.htm#anchor_1559670130302.

[9] Katherine McKittrick, “Introduction: Geographic Stories,” in Demonic Grounds Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), xiii-xiv, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttv711.3.

By: Shemika Curvey