Scholars have noted that what constitutes someone as “disabled” in today’s society has its roots in slavery. Jenifer Barclay explains that laws were created with the sole purpose of regulating how much an enslaved person was worth based on their intellectual and bodily ability, physical appearance, and its effects on the person’s ability to work and produce economic value to slaveowners (2014).

“...even at their best, enslaved Blacks were inherently defective, deviant, depraved– in a word, imperfect… [the] baseline against which [the enslaved were judged] was, of course, white men… whose whiteness was an unmarked marker that assumed normativity and encompassed a range of beliefs, behaviors, and appearances that extended to the body and mind… whiteness claimed whole, able bodies and rational, sound minds as its ontological terrain, the embodiment of not only ‘normal’ but also ‘perfect.’ In contrast, Blackness represented various forms of defectiveness and abnormality– one might say disability– whether these characteristics were real or imagined, visible or invisible, physical or psychological… the law played a fundamental role in producing what was, by that time, a deeply entrenched and seemingly natural nexus of associations between Blackness, defectiveness, and disability… slavery dictated that a person’s perceived abilities and capacity to work determined their value… these laws constructed a legal narrative of Blackness that persistently embedded a range of qualities often associated with disabilities within the metalanguage of race.” (Barclay 2014)

Similarly, today a person’s “ability” is marked by their capacity to work and produce economic value based on intellectual and physical ability and appearance. Considering Virginia’s deep history with the enslavement of Black people and its subsequent history with various forms of resistance to freedom, it comes as no surprise that there is also an additional, obscured history tying together the threads of racism, ableism, and education in Virginia.

During the era of chattel slavery, Virginia had a large enslaved population, and as the Civil War ended and Reconstruction began, Virginia was one of the most resistant states to treat the formerly enslaved as free people; in fear that white people would no longer control the land the way they had, whites adopted policies meant to restrict the movement and ability of Black folk throughout the state, usually referred to as Black Codes or Jim Crow laws.

“The 1902 revised constitution firmly established the legitimacy of Jim Crow, and successfully disenfranchised four-fifths of the Black voting population and a large number of poor whites. The control of government lay with the literate and the privileged, leaving those who were on the margins of society… without a voice.” (Eckenrode-Gibson 2007)

Subsequently, in the early 1900s when a new “scientific framework” called eugenics was established and introduced to the general population, Virginia adopted this new way of thinking with ease, fast becoming one of the most prominent endorsers of it. Eugenics refers to the elimination of unwanted or undesirable traits by sterilization or straight-up eradication of those deemed disposable to society. Francis Galton, cousin of Charles Darwin and one of the main advocates for eugenics, describes it as “the study of all agencies under human control which can improve or impair the racial quality of future generations” (National Human Genome Research Institute 2022). Eugenics is rooted in racism and puts the ideals of whiteness on a pedestal, rendering anything outside of it as something that must be eradicated; in other words, those Othered, minoritized, and/or racialized populations– Black, Indigenous, Asian, Hispanic/Latine, queer, physically and mentally disabled people, etc– and their cultures are considered outside of white standards and disposable by default.

“...[the tainting] of white blood with any Negro or racially inferior blood was thought to mongrelize the white race… Many Americans believed that the nation would be overrun by the inferior, and some went to the extreme to suggest that assisting the poor and improving their environment could result in the preservation of those meant to die out… Late 19th-century western values placed moral judgments on those who were dependent due to their inability to work, placing a critical value on self-reliance. They believed that those who were being provided for would lose their willingness to ever provide for themselves, thus leading to pauperism, a condition of persistent dependence. Such dependence, they felt, led to the criminal behavior and squalor of the poor.” (2007)

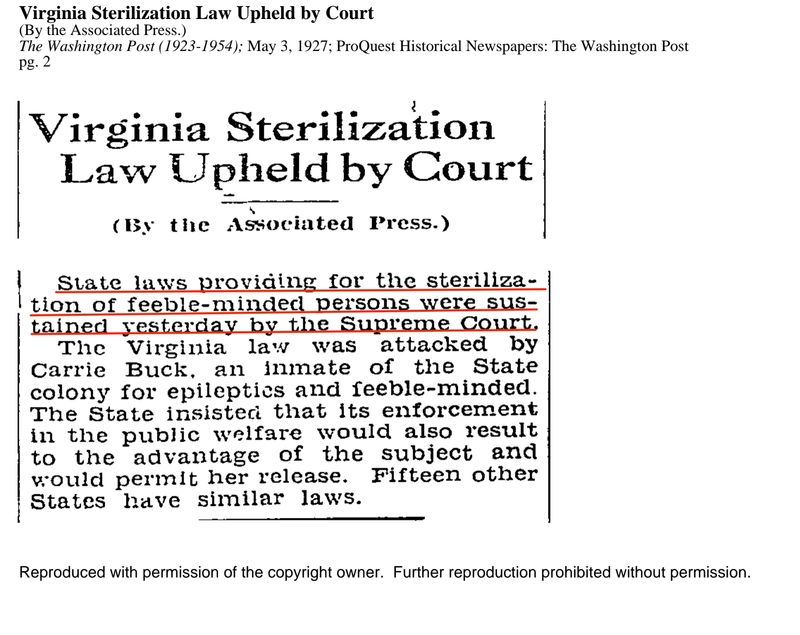

In a Virginia Health Bulletin sent out in 1915 by William Plecker, a popular Virginian eugenicist, he wrote in part, “...only the good tree bears good fruit... to this class of the unfit belong the insane, the epileptic, the alcoholic, the hereditary criminal, the syphilitic, the imbecile and the idiot, and none of these should reproduce.” Some of these categories, which have no real truth or validity to them at all, are quite broad and subjective in scope, such as “insane, imbecile, idiot”; others are clearly steeped in racism, like “alcoholism, the hereditary criminal”; and others, like “epileptic” and “syphilitic”, are simply health concerns. The main focus of these “scientists” was not on how society could better help these populations because eugenicists wanted to maintain white supremacy by eradicating people outside of their likeness. One of their most popular claims that resonate through today is that if social programs existed for these communities that provided actual care and accommodations, they would always be “dependables” and never become productive members of society, or, put more plainly, economically beneficial to whiteness. The two popularly proposed “solutions” after death were sterilization and segregation from “normal society”, so as to not “taint” the white population.

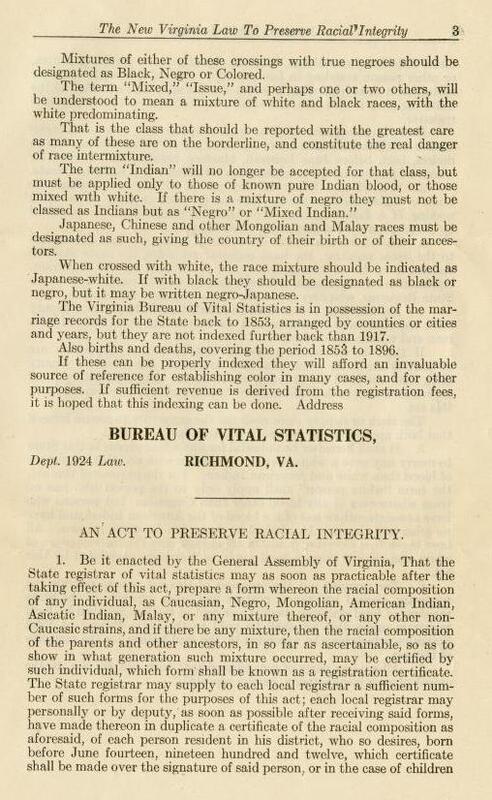

In 1924 during the height of the eugenicist movement, Virginia passed the Racial Integrity Act into law in an effort to “preserve the integrity of the white race”, which prohibited interracial marriage and put people into strict categories of either “colored” or “white” (1924). This series of laws defined a white person as someone “who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian” and established the “one-drop rule”, which stated that anyone with any African ancestry, no matter how far back in their lineage, was considered “colored” (Wolfe 2023). Additionally, these laws attempted to strip Indigenous people of their legal rights to sovereignty by attempting to erase “Indian” as a category altogether in favor of “colored”, as well as assimilate any immigrants into either/or categories (2023). Interesting to note here is the pattern by which the American government attempts to erase Native people throughout history by disappearing their identity altogether; for instance, in the 1700s, Virginia was the first colony to pass “blood quantum laws”, which restricted the rights of any Indigenous person who was “half-blood or less”. While Blackness seems to taint the blood altogether, Indigenous blood has the ability to disappear over time. These laws lasted well into the 1960s and came to an end with the Loving v. Virginia case of 1967, but the repercussions of the base ideology of these laws is evident still today.