20 Days In the Bottom of a Vegetable Cart

For generations, families and local museums in a small town called Warsaw in New York have told a story that could be the answer to the question of where Sarah Ann fled with her children and if she was successful. The story goes that around 1850 a pregnant woman named Mary Jones (sometimes Ann or Mary Douglas) fled the Northern Virginia/DC area with her 7 year old daughter Mary (later Mary Eliza or just Eliza). They had been assisted by a handful of east coast abolitionists along the Underground Railroad who brought them eventually to Warsaw, a north western section of New York near the Canadian border in the bottom of a horse drawn cart. The person who helped them escape is said to have built a box in the bottom of a farm wagon.[i] The pregnant woman and her daughter crawled in there and were given a water jug and some food and the box was then covered with market vegetables.[ii] They laid this way for the entire journey which took them around 20 grueling days to complete as they passed through Maryland, Pennsylvania, and headed westbound through New York.[iii]

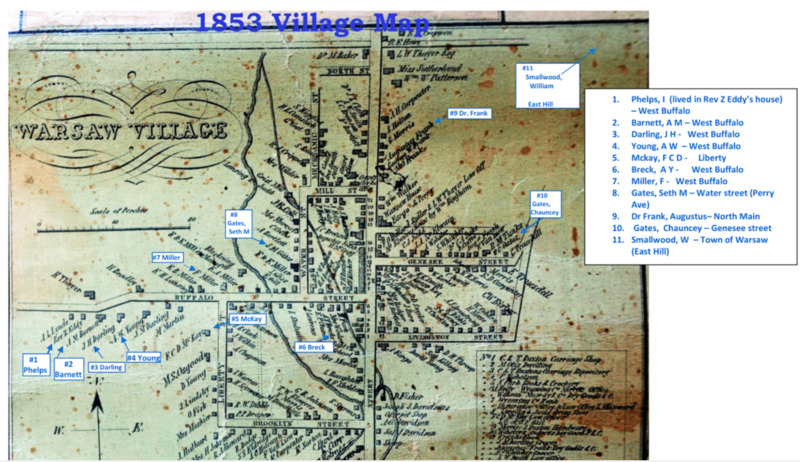

The first household they are said to have arrived in was the Smallwoods of East Hill. After examining topography and a village map from the time, it becomes clear that this was not the city of East Hills, New York, but rather a neighborhood of Warsaw that was located on an eastern hill (See map to the left).

Michael and Elizabeth Beedon Smallwood are fairly well known today for their abolitionist activity. A particularly cinematic story tells of Elizabeth often sitting all day in an old rocking chair on a rug. The rug covered a trap door in their wooden floors to where enslaved people hid until being moved again.[iv] According to town historians, the Smallwoods also frequently hid enslaved folks in swamps near their home.

Smallwood family histories claim that when the pregnant woman (Mary Douglas/Jones) and her daughter Mary arrived at their home, she very soon after gave birth in their kitchen to a healthy baby boy she named Charles William after William Smallwood, the grandfather of the family. The three of them remained in this house while she recovered and until the Smallwoods felt confident that officers from the South were not still looking for them or had not realized where they had gone. At this point, the mother and her two children were transported to different homes: the Darlings and the Barnett’s. We know this because they show up on the census… for the first time since their escape.[v]

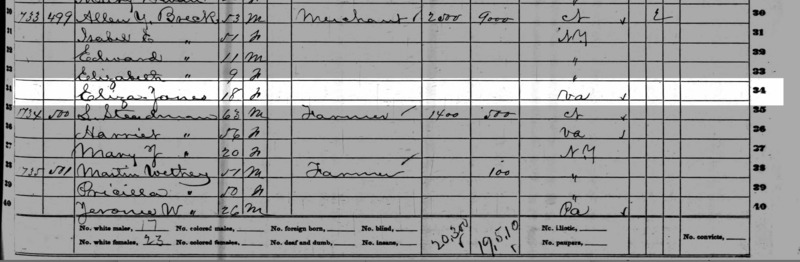

The Darlings, also known in the community for their abolitionist efforts, housed the children, listed as Eliza (age 8) and Charles Jones (age 4 months). In the Barnett household, the census documented Ann Jones (age 25). Ann Jones was listed as Black and her birthplace marked as Virginia. Eliza and Charles, on the other hand, while also being documented as from Virginia, were listed as white. Clearly the children were light enough in skin tone to pass for white, and this would likely afford them some safety. Their light skin tone evidenced here is reminiscent of Mary Follin’s description of 7 year old Mary as a “bright Mulato girl.”[vii] Alternatively, this census begs questions that may never be answered. Among them: how were alarm bells not raised at the fact that these two children had been born in the South?... Especially Charles who in June, when this census was taken, could have been 4 months old at the absolute most. Looking closely at this record and the village map also reveals the important detail that Ann Jones was hidden separate from her children, but deliberately right next door both to maintain discretion and keep them all together.

According to the written Warsaw histories, the mother (Ann/Mary) died of tuberculosis within a year of the birth of Charles and it was at some point after this that the children were split up into different households.[viii] The question of why this may have happened is one that is answered by the 1860 and 1870 census records and brings to light yet another incredibly significant story.

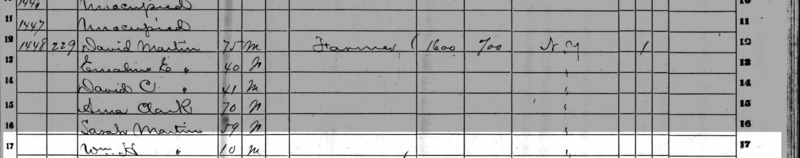

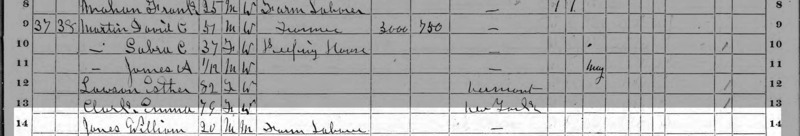

By 1860, Mary Eliza and Charles William had been split up. The 1860 census places Eliza in the Breck household.[ix] She is 18 years old, from Virginia, and according to the record, white. In 1860, 10 year old William was in the Martin household and also listed as white.[x] However, by the time he became an adult, he could no longer pass, and so while still living with the Martin family, he was listed as mulato and was documented a “farm laborer” on the 1870 census. Perhaps they were split as they got older because Charles William’s Blackness was becoming more visible, or perhaps also having more than one adopted or added child was suspicious. With the 1870 census, it is likely that Charles William was given the laboring occupation on paper to avoid any question of why a Black man was living with their family.[xi]

The idea of racial passing, hiding in plain sight in order to protect themselves, being split up from family yet another time, and having to hide or erase their own identities in order to survive is compelling. Especially as they were never discovered or revealed. In the absence of their mother and in their fugitive existence, Mary and Charles had to abandon their identities. The two of them grew up in these pseudo-adopted households and lived their whole lives in New York. Interestingly enough, one of the only physical relics of this family is the adult home of Mary Eliza and her husband William Burghardt.[xii] Their marriage decidedly marks a shift in Mary’s life when she is able to gain back some piece of her identity because William was a free Black man. Having passed as white for her entire life after the escape she likely was still haunted by, when the war ended and she was finally free from the threat of the Follin’s finding her or her brother, she embraced her Blackness and began the life her mother longed, wished, and sacrificed for her to have.

[i] Young, Andrew W. “An ‘Underground’ Escape.” In History of the Town of Warsaw, New York, 364. Buffalo, New York, 1869.

[ii] Snodgrass, Mary Ellen. “Burghardt, Mary Eliza.” In The Underground Railroad : An Encyclopedia of People, Places, and Operations, 87. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 2008. https://archive.org/details/undergroundrailr0000snod/page/86/mode/2up.

[iii] “1860 Census Breck,” 1860. Record Group Number: 29; Series Number: M653. The National Archives.

[iv] Snodgrass, Mary Ellen. “Burghardt, Mary Eliza.” In The Underground Railroad : An Encyclopedia of People, Places, and Operations, 87. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 2008. https://archive.org/details/undergroundrailr0000snod/page/86/mode/2up.

“1870 Census David Clarke Martin,” n.d.

[v] “1850 Census Joshua H Darling.” In 1850 United States Federal Census [29], 1850 (roll M432). National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the Bureau of the Census. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/8898354:8054.

[vii] Mary Follin. “Fifty Dollars Reward - Feb 28.” Alexandria Gazette, February 28, 1850. America’s Historical Newspapers 1 & 2.

[viii] “A Former Warsaw Boy’s Interesting History.” Masthead Wyoming County Times, April 17, 1919.

[ix] “1860 Census Breck,” The National Archives in Washington D.C.; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29; Series Number: M653; Residence Date: 1860; Home in 1860: Warsaw, Wyoming, New York; Roll: M653_883; Page: 751; Family History Library Film: 803883, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/49059516:7667?tid=&pid=&queryId=94ab4bf39aa8f21e0a84830183d7edbb&_phsrc=bOu107&_phstart=successSource

[x] “1860 Census David Clarke Martin,” In 1860 United States Federal Census [29], 1860 (roll M653), National Archives and Records Administration, Records of the Bureau of the Census. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/49055097:7667

[xi] “1870 Census David Clarke Martin,” The National Archives in Washington D.C.; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29; Series Number: M653; Residence Date: 1860; Home in 1860: Warsaw, Wyoming, New York; Roll: M653_883; Page: 717; Family History Library Film: 803883

[xii] “Mary Eliza Burghardt Obituary.” Wyoming County Times, May 12, 1898.