Fade to White – Ilda and the Right to Remain

Under tall trees off a rolling stretch of suburban tarmac, Braeburn Drive in Annandale, Ilda Pool occupies a small and pleasant glen. With a wide, flat parking lot, crooked bike rack and low-slung brick pavilions, it looks like the many other neighborhood swim clubs dotting curvy streets and cul de sacs that criss-cross Fairfax County’s former farms. Most, like “Canterbury Woods” or “Burke Station,” bear the names of local landmarks or branded housing developments. But for what are Ilda Pool and the nearby Woods of Ilda subdivision named – a person? a place? some quirky local legend, perhaps?

In a way, it’s all of those, though probably no one toweling off there on a summer day has any idea how. Ilda was a place named for a person that in some ways faded into a semi-forgotten legend. Few locals remember it anymore as a community – an actual geographic spot. And even fewer know it for what it represented: an achievement of Black placemaking in Virginia in the face of daunting racism. Founded by formerly enslaved Americans, Ilda took root in Fairfax’s landscape by creating farms, homes, and an iconic local business, but also through immaterial totems of belonging in America: voting, petitioning the government, and joining and supporting institutions like churches and cemeteries and schools.

“Placemaking” as a term serves many theoretical uses, but at Ilda it can be interpreted simply: creating a geographic presence and social identity in what had been a dusty, nameless corner of the former Ravensworth land grant. Whites, too, owned land in Ilda (in fact, they appear to have occupied most of it), but the area became a place, a landmark to navigate by, only after its first Black owners arrived. The Gibson and Parker families put Ilda on the map by building a blacksmith shop they ran for nearly fifty years at a prominent intersection -- the ten-mile mark on heavily trafficked Little River Turnpike where it meets (still) with Guinea Road.

They called their hamlet “Ilda” in honor, family tradition holds, of the Gibsons’ daughter Matilda. She would grow up to marry a son of their friends and partners, the Parkers, and Matilda and Page Parker would take over the smithy from their fathers and run it for a few years.[1] And Matilda’s pet name would take hold: More than half a century before the first lap was swum at Ilda Pool in 1965, “Ilda” started appearing on government records. It eventually graced a school, a church, and a Federal post office. By 1907, it also regularly appeared in newsprint, in social columns like the “Local News Briefly Told” feature of the Fairfax Herald.[2]

Unlike Matilda herself, though, Ilda Church and Ilda School were white, as in whites-only, and the Herald’s politics aligned with southern-leaning Democrats.[3] When Ilda comings and goings and ice cream socials made the paper, it was white residents garnering the ink. As the Turnpike grew smoother and wider, becoming state Route 236 and now covering eight lanes with perhaps more to come, Ilda grew denser and whiter. Traces of its founders pretty much disappeared.

This exhibit looks at how and why the vibrant place I call Black Ilda faded into the “colorless,” placeless Ilda of Ilda Pool. How did it grow into a local landmark only to disappear from the map? Why, after their forebears’ intense investment of money, labor, hope and love, did Ilda descendants miss out on the windfall of generational wealth ushered in by Fairfax’s “bedroom community” building boom of the mid-1900s? When local farmers sold for thousands of dollars per acre land that their parents or grandparents may have bought for just ten? Mapping the paths of the Gibsons' and Parkers' offspring and grandchildren shows they had scattered by then not just elsewhere in Fairfax but as far as New England and Michigan. Back in Ilda, possibly just one Black farm family, the Johnsons, remained into the 1950s. That's their daughter, Viola, pictured at top.

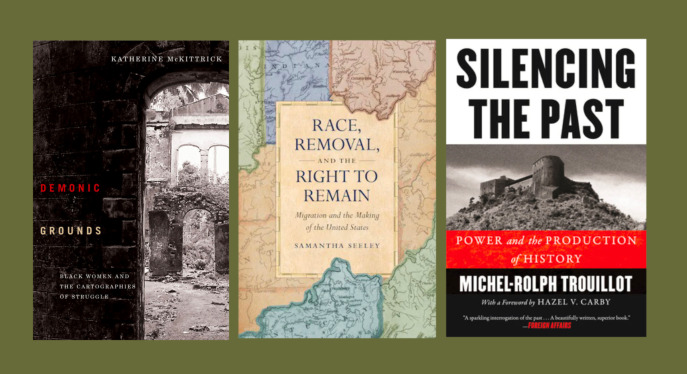

Historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot might have seen in those mid-century bulldozers a metaphor, a “burying” of Ilda. “As sources fill the historical landscape with their facts,” he wrote in Silencing the Past, “they reduce the room available to other facts.” Trouillot describes how dominant narratives, crafted from details of history’s winners, work to “silence” stories of the poor, the defeated, and the less powerful.[4] Trouillot memorably describes an instance of such silencing that reverberates at Ilda: He relates that Christophe, prince of newly independent Haiti, executed his rival, Col. Jean-Baptiste Sans Souci, and then erased his name from memory by taking it for his palace, “Sans Souci.” Until Trouillot unpacked the story, "Sans Souci," to Haitians, meant not the brave independence fighter but Christophe's grand pile of the same name - the now derelict Palace of Sans Souci.[5] As Trouillot revives the story of Sans Souci the man, this project aims to elevate Ilda as a Black place nearly bulldozed from local memory.

Erasing Black Ildans' ties to the land deepens a perception of Fairfax's African Americans as, to quote Black studies scholar Katherine McKittrick, “ungeographic.” “[S]pace and place give black lives meaning in a world that has, for the most part, incorrectly” deemed them ungeographic, McKittrick writes in Demonic Grounds. In Ilda's case, an actual Black geography was rendered “un-Black.” The bleaching of Ilda epitomizes McKittrick’s model of “discourses that erase and despatialize [Black people’s] sense of place.” Her redress for such erasures includes mapping their “physical landscape and infrastructures” as well as their “social relations in and across space” -- a task I will venture in the pages that follow.[6]

Land changes hands, of course, and people move around, often deliberately, to pursue better livings and better lives. But history shows us that voluntary departures – the pull of relocation – are more often an option for white and privileged populations. African Americans in Fairfax and elsewhere have moved a lot, too, but often without choice, pushed by some combination of forces that may include redlining and exclusion, pollution inequality, abuse of eminent domain, political hostility and even outright violence. The demise of Black Ilda owed to few overt “pushes” but still appears, from this distant vantage point, to have been a slow expulsion.

The inchoate instinct that “people shouldn’t have to move” – to leave places they’ve made and call home – gains conceptual ground in the work of historian Samantha Seeley, author of Race, Removal, and the Right to Remain. Perhaps not the first scholar to conceptualize a distinct right to stay put, Seeley gives the idea keen and poignant voice in tracing Native and African American resistance to displacement in the early U.S. Republic. While “white Americans used exclusion to shape the racial geography of the nation,” she writes, the peoples they would use as pawns built a novel case “that a permanent home lay at the crux of freedom or sovereignty.”[7]

Seeley’s work addresses events of 200 years ago, and a century has passed since Ilda faded to white, yet the issues they raise still confound us. Gentrification, zoning and redlining, climate change, immigration policy -- a raft of contemporary assaults restrict the rights of poor and brown people simply “to remain.” Our national lore reflexively celebrates white stakeholders, in classic tropes of “frontier homesteaders” and “suburban (or urban) pioneers.” Yet Ilda’s founders were nation-builders, too, also staking out territory, bringing grit and skill to the project of building wealth, family and community – all with the intent to remain.

To understand the fading of Black Ilda, I will look first at placemaking – what it took and what it meant to build a Black enclave on war-ravaged land in post-bellum Northern Virginia. Second, I will explore how such communities, at Ilda and nearby, made themselves “geographic,” solidifying their presence materially and through social networks, cultural creation, and government engagement. Ilda’s founding families signed deeds, voted, paid taxes, ran for office. They signed petitions and filed lawsuits. They supported schools and built and joined clubs and churches and cemeteries. At the point where all those efforts proved insufficient, we reach my final question: What forces destabilized Ilda to the point where no amount of grit, enterprise or social bonding could ensure Black permanence there?

These same questions of Black permanence and displacement swirl every day around the neighborhood I live in, in Southwest Washington, D.C. Crumbling public housing jostles side-by-side here with sturdy, well-kept residential complexes, including my own, in the blocky “Brutalist” style of the 1960s. All of it dates to a notorious episode of Federally funded displacement that pushed out some 23,000 members of Black and immigrant families, razing their homes, businesses, and social networks in the name of “urban renewal.”[8] Recent luxury development around “The Wharf DC,” the shiny, $3.6-billion, mixed-use riverfront mega-complex, has left low-income locals wondering if they will be priced out next.

When I began studying Ilda, I was already active in a movement to “save” our neighborhood’s last two undeveloped lots for affordable uses. (We are urging the city to buy them.) The issue made sense to me, rationally, as a simple matter of equity. But it suddenly got personal when I discovered that a son of Ilda lived on my block. Wesley Gibson resided almost 40 years at 1216 Sixth Street SW, a stretch of city street that no longer exists, mere steps from my current home. Wesley died in 1941, too early to lose his right to remain here, but what of his wife and children and friends, I wonder. Like residents of Fairfax today, like all of us when we consider that Indians once dominated lands we now occupy, I have benefited from other people’s not remaining. Now I know one of them came from Ilda, and I know his name.

[1] “Ilda Historical Marker,” accessed April 20, 2023, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=37906.

[2] “Local News Briefly Told - Ilda School Hallow’een Fundraiser,” Fairfax Herald, October 25, 1907, https://virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=FHE19071025.1.3&srpos=15&e=--1865---1960-190-en-20-%2cADA%2cTFCI%2cFCJS%2cFFGZT%2cFHE%2cFSD%2cTI-1--txt-txIN-ilda-------.

[3] Anne McCrery, “A History of the Fairfax Herald,” The UncommonWealth: Voices from the Library of Virginia (blog), 2015, https://uncommonwealth.virginiamemory.com/blog/2015/08/14/6623-2/.

[4] Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press, 2015), 49.

[5] Trouillot, 59–60.

[6] Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), xiii.

[7] Samantha Seeley, Race, Removal, and the Right to Remain: Migration and the Making of the United States (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2023), 3.

[8] “Urban Renewal: The Story of Southwest D.C.,” Whose Downtown? (blog), May 17, 2013, https://whosedowntown.wordpress.com/urban-renewal-the-story-of-southwest-d-c/.

Mandy Katz