Violence, Compassion or Both?

The life of an enslaved black woman was indelibly marked by racialized sexual violence situating her “within the broader system of servitude-as an inhuman racial-sexual worker, as an objectified body, as a site through which sex, violence, and reproduction can be imagined and enacted, and as a captive human.”[1] So, this system of servitude can not be viewed as separate from acts of infanticide by enslaved Black women, instead it must be seen as responsible for them. Therefore, questions of violence should be directed toward its purveyor, the enslavers and upholders of the institution.

Leaning again into McKittrick’s theory, it is imperative here to consider “black women’s geographies, such as their knowledges, negotiations, and experiences.”[2] How might experiencing violence daily manifest? And what happens to the mind when experiencing repeated violence? What “negotiations” were they faced with making for their own safety and survival? But also, what “negotiations” might they have made for the child’s safety? And therefore, could infanticide have been an act of compassion to spare the child?

These are the questions asked of the archive when I encountered Fanny (1844), Fanny (1852), and Kesiah (1832). (see story map) Accused of the same crime, “archival powers” documented them in similarly violent ways but with different context. Then they disappear upon meeting a common fate: imprisonment, sale, and transport (see penitentiary ledger). The differing context however, whether intentionally or unintentionally disclosed, allows us to glean small insights into their experiences and negotiations of “space, place, and location in their physical materiality and imaginative configurations.”[3]

Fanny (1844) entered the archive at Richmond College, Henrico County, Virginia, on the 19th of May. According to the archive, after giving birth to a “female mulatto infant,” Fanny committed infanticide (see image left). The reason the coroner included the supposed racial identity of the child as “mulatto” is unclear, particularly because “Partus” law ensured the child would be enslaved regardless. It’s fair to deduce Fanny’s pregnancy was a result of violence by a white male and that directly informed her actions. In a case like Fanny’s, Letty, from Brooke County, Virginia, professed her innocence in 1822 case, Commonwealth v Letty. However, the coroner’s inquisition alleges she said, “if the child had been one of her own colour, she would not have done as she did.”[4] Again, what happens to the mind when subjected to repeated physical violence? Victims of rape and sexual assault dissociate from their bodies to survive, so how might that also impact birthing as a result?

In volatile environments, what ways might they have exercised agency? Fanny (1852) of Albemarle County, Virginia, who entered the archive through doctor testimony in the coroner’s inquest, offers insight. Fanny is noted to be cooking dinner while enduring the doctor’s questions about the birth of her child. Said to have denied giving birth recently, the archive revealed Fanny had at least one other child around the age of 3 whose location goes unmentioned. How could prior birthing of children sold and/or brutalized have impacted Fanny?

Upon discovering the placenta, Fanny is alleged to have said she gave birth to a still born child which she violently disposed of (see story map for details). However, according to the doctor’s testimony, the child was found “in the feather bed upon which she slept.” In Birthing a Slave, Marie Schwartz highlights that, “when infants did not thrive, they [the enslaved] sought to observe funerary rituals and to express grief in accordance with the conventions of the slave quarters.”[5] Could we understand Fanny’s denial and concealment of her child as grief? Was she attempting to exercise agency over laying her child to rest?

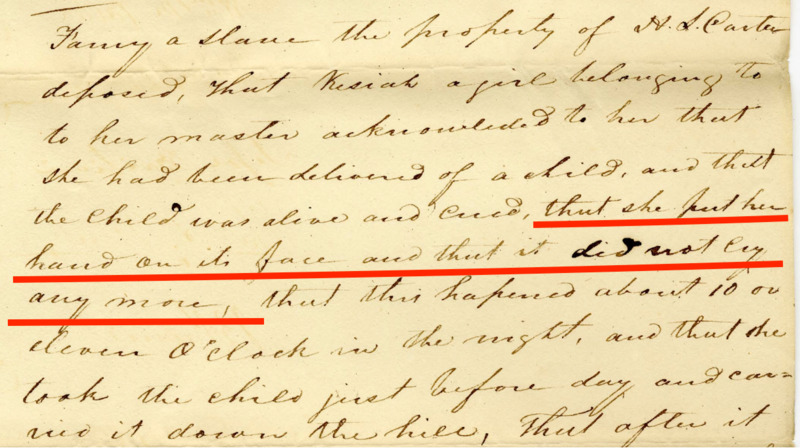

Schwartz also points out that, “members of the owning class [mis]interpreted stories of women maintaining secrets about the birth of babies as evidence that enslaved women could not be trusted to care for children or even tell the truth about pregnancy and childbirth.”[6] I encountered Kesiah (1832) of Henrico County, Virginia on the 15th of April, navigating this perception. Her archival event demonstrates how compassion accompanied the “negotiations” enslaved women were forced to make. I believe compassion can be found both in Kesiah’s actions as well as the oral testimonies of the enslaved women she lived with. According to Lidia and Fanny’s testimony, Kesiah was alleged to have denied being pregnant, but acknowledged to them that at ten or eleven the night prior she delivered a female child that cried. That she then put her hand on its face, and it did not cry anymore (see image left). And before daybreak, she carried the child down the hill where she deposited it. Could Kesiah’s denial of pregnancy been an endeavor to spare her female child a shared fate?

It's also worth noting the language, transcribed as testimony, between the three enslaved Black women. Subtle but clear differences exist between their testimonies and the coroner’s. Could Kesiah’s language and description of events also signify compassion? Further, there was great danger involved with moving under darkness. So, how can we interpret her carrying her child down the hill at daybreak to bury? What could the quiet of sunrise imply? Prayer? Ritual? Can we see an alternative narrative that allows infanticide and compassion to coexist? McKittrick reminds us, the “violences of slavery, as they are spatialized, do not disappear when black women assert their sense of place.”[7] Therefore, as they struggled to navigate violence as well as the spatial constraints of plantation-life pregnant, how might we reconsider the “negotiations” made for survival?

[1] Katherine McKittrick, “Introduction: Geographic Stories,” in Demonic Grounds Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), xvii, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttv711.3.

[2] McKittrick, “Introduction: Geographic Stories,” x.

[3] McKittrick, “Introduction: Geographic Stories,” x.

[4] Wilma King, “‘Mad’ Enough to Kill: Enslaved Women, Murder, and Southern Courts,” The Journal of African American History 92, no. 1 (2007): 42-43, https://doi.org/10.1086/jaahv92n1p37.

[5] Marie Jenkins Schwartz, “Procreation,” in Birthing a Slave: Motherhood and Medicine in the Antebellum South (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), p. 226.

[6] Schwartz, “Procreation,” 209.

[7] McKittrick, “Introduction: Geographic Stories,” xvii.

By: Shemika Curvey