Destabilizing Ilda - Bulldozing Black Geographies

By the time Marion Dobbins was singing her heart out around her grandmother’s piano, Black Ilda was but a memory, with the Johnsons isolated as either the only or one of the few African American families remaining. As Black Ilda withered, a contrasting example emerged in the community of Falls Church, led largely by members of the Tinner and Henderson clans. In a rare and early case of a Black community’s leveraging law and solidarity, the Tinner Hill enclave successfully resisted government-mandated displacement. The Falls Church Town Council in 1915 proposed confining its “Negro residents to a small section of the town” to usurp their location for a segregated white zone. Rather than leave their homes of long standing, locals formed a Colored Citizens Protective League – later affiliated with the NAACP – to fight back. They “hired a Washington lawyer and brought suit to prevent enforcement,” and they prevailed. Some Tinner descendants today live in or on the sites of their forebears’ Falls Church homes.[2]

It’s tempting to ask why Horace and Margaret, Moses and Emily and their children didn’t likewise organize to preserve their place in Ilda. Did they ever mull setting aside land for a church or a school? Forming social clubs or activist associations? At the same time, we must also ask, “Why should they have had to?” Why did it take both extraordinary effort and fortuitous circumstances for Black hamlets in Fairfax simply to persist? Why did just hanging on require fortitude and enterprise beyond even the abundant human resources of Ilda? This page looks at how segregation and racism eroded community at Ilda and beyond.

As is clear from the Ilda's Institutions map (previous page), in the absence of local society, Ilda’s Black pioneers could choose among a relative abundance of institutions in nearby communities. For churching alone, they worshipped over the years at congregations including Galloway Methodist, Second Baptist, First Baptist and Mount Pleasant. But while families living in those communities likely built their social lives around church, visiting several times a week, living miles away would have dampened Ildans’ participation and sense of belonging.

Ilda did have two local churches, but neither accommodated Black people. Wakefield Chapel (still standing, though no longer a house of prayer) began construction in 1897 between Ilda and Falls Church. A later congregation established Ilda Church on Little River Turnpike in 1908, presumably unaware they were naming it for a woman who, if she wasn’t already, would soon be co-chairing the Fairfax Colored Association.[3] While Wakefield hewed to the traditional Methodist-Episcopal tradition,[4] Ilda Church’s affiliation with the “Methodist Episcopal South,” the breakaway offshoot, explains a 1977 Wakefield Chapel history, “indicates … the fierce, defensive pride of the defeated Confederacy.”[5] Still, like so many other American communities reconciled in the early 1900s around Lost Cause dogmatism, the two communities found common ground in the end, as white Christians. As the Wakefield history blithely recounts, “Fortunately, the bonds of their common Methodist heritage proved stronger than denominational or political rivalry. Over the years, members of the two churches began to attend each other 's services.”[6] Black Ildans would continue worshipping elsewhere.

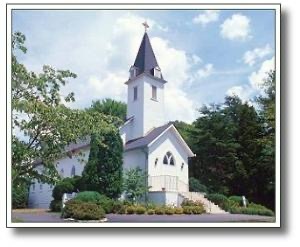

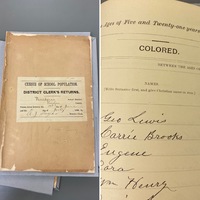

As with churches, so it was with schools, though in this case it was not private congregations but the tax-supported county and Falls Church School Board, that discriminated against the Black children of Ilda. While youngsters like Viola Johnson (later Richardson) traipsed to Merrifield, once they reached high school, their only options (discussed on previous page) were either to board the early bus to a vocational school in Manassas or find a way to matriculate at Black schools in D.C.[7] As late as 1965, the only children from Ilda attending local schools would be white. “The extreme inequity of segregated schools was surely a factor in the long-term decline of Ilda,” concludes Tom Shoop.[8]

Comparisons of school spending and facilities across Fairfax crystallize this systemic racism: “A Virginia Education Commission study in 1920 found that the cost of instruction per pupil in Fairfax County varied from an average of $13.29 for each white child to $6.44 for each black.”[9] Falls Church activist E.B. Henderson, describing achievements of the NAACP chapter he helped found, recalled a time of disparities in Fairfax Schools such that the Falls Church Colored School lacked even drinking water, while white children attended handsome brick facilities whose teachers received higher pay. Adding insult to economic injury, “‘Teachers of colored children were responsible for janitorial work, whereas such service was … provided in schools for white children.”

Back in Ilda, making a living was getting harder. The early 20th century was not an easy time for Fairfax agriculture. White farmers got what benefits they could by flexing political muscle in the pre-World War years, when “the acid test of an incumbent’s performance was the length of his list of contributions to farmers” – largesse that took the form of grants to fight peach blight, free seed packets, and (promises, at least, of) free rural mail delivery.[10] But how many of these emoluments would have flowed to Black farmers, especially after a 1902 revision of Virginia’s voting laws quashed their electoral clout?

With or without aid, agricultural decline in the ensuing years cut across the color line, despite a productive dairy sector and a few individual farm successes. A University of Virginia survey in 1924 found that the rate of mortgaged farms in Fairfax, 20 percent, exceeded that of most Virginia counties. Officials blamed a dearth of agricultural cooperatives but also global factors like low market prices and tight money.[11] Meanwhile, the growing popularity of “gentleman farms” was changing the landscape, popularized by tastemakers like Andrew Jackson Downing, who in his 1841 Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening advised “how to convert an ordinary farm into a gentleman’s estate or ‘Country Seat.’”[12] The University of Virginia study cited the “glaring inequality” of offering more favorable tax assessments for such properties than for working farms.[13]

As much as they valued land, Black landowners, especially, may have found farming un-economic in Fairfax, even before the turn of the century, according to historian Scott E. Casper’s analysis of communities around Mount Vernon. Already by 1890, he writes, “the opportunity to subsist solely as small farmers barely existed” around Alexandria, evidenced by census reports recording most Black residents’ jobs as laborer, laundress, railroad worker, house servant and the like.[14] The 1930 Gum Springs and Spring Bank census listed “virtually every black landowner in as something other than a farmer, and indeed, as not living on farms at all, even people who lived resided on the same property where they or their parents had lived in 1910…”[15]

Farm straits may have suppressed blacksmithing demand, but an even bigger blow would have come from the increasing popularity of automobiles. The Fairfax Herald in 1916 tallied some 200 vehicles in the area and deemed them “indispensable to modern business life;” just four years later, the state counted almost 3,000 vehicles in Fairfax.[16] Still, horse plows and carts remained in use, farm implements needed repairs, and equestrian uses -- recreational and otherwise -- persisted in the county. A white-owned smithy in Falls Church, Harmon’s Blacksmith Shop, stayed in business into the late 1950s. For its last 40 years, it was known for the skilled work of African American blacksmith Henry Simms, “who was able to shoe 25 to 30 horses a week, most of them from fashionable schools.”[17]

Perhaps the only thing holding back car culture at all was the sorry state of local roads, another damper on prosperity. A public agricultural agent's work took him all over in those days, and Fairfax’s representative complained in 1917 “that ‘there were very few miles of hard roads in the county and much of the work had to be done with horse and buggy,’” the terrain being too rough for his new Ford.[18] Even as the county’s upwardly mobile moved into the automotive age, however, it's worth noting that Horace Gibson’s son Strother, when he died at age 81 in 1927, was still commuting to a job, as an estate caretaker in Herndon, and getting there on horseback.[19]

That county agent with the under-used Ford underlined the economic and social costs of crude infrastructure when he observed in the 1920s that Fairfax farmers “in the back sections with its bad roads” were driven “to sell their homes for less than what the buildings cost them in order to get away.”[20] Certainly for Black Ildans, road conditions would have exacerbated not just rural but racial isolation. In 1889, area farmers of both races began petitioning for a direct route from their Turnpike hamlet to what they called the Falls Church - Fairfax Court House Road, now Route 29. Such access would have enhanced life for Black Ildans immeasurably, connecting them to schools and church brethren in Merrifield as well as, by 1900, their adult children and grandchildren living there. But almost two decades would pass before today's Prosperity Avenue closed the gap, by which time Ilda had few Black residents left.[21]

Only in 1920 would the county would issue its first road bond, for $500,000 to repair the very Turnpike running by Gibson’s shop -- again, well after Ilda's founding families had decamped.[22] Horace Gibson’s farmland had been divided and sold after his death, at age 95, in 1913.[23] In 1932, county probate officials announced the sale by auction of the last of the scattered Parker family’s acreage at Ilda, about eight acres in all. Together, the two men had amassed more than 400 acres, but Ilda was no longer theirs.[24]

Bleak financial prospects could have driven the push, for Black Ilda's next generations, away from the hamlet. The Ilda Diaspora Map below gives an idea of how they flowed out to places like Merrifield and D.C. but also cities in the north. But perhaps even more of a push came from the constant weight of social oppression in Fairfax, where by 1915, the Ku Klux Klan had reorganized, even serving as “‘the drawing cards’ at agricultural fairs and at gatherings for ‘community betterment.’”[25] “[H]ow can you participate in a community,” asks historian Patricia Donahue, “if you cannot join it in the first place?” Donahue’s was addressing civil rights challenges faced some forty years after Ilda’s heyday, but she could be describing Ilda when she writes, “[I]nstitutional exclusion or racism is a form of negative participation.”[26]

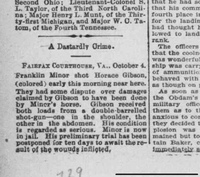

We know from earlier discussion that at least some of Ilda’s (male) elders registered to vote, even after the leveling of a poll tax, literacy tests and other obstacles. Yet even in a county far less hostile than regions farther south, Jim Crow was increasingly on the local ballot. In 1889, when memories of Reconstruction were still fresh, progressive Fairfax Republicans had put forward a Black candidate for constable. The resulting diatribe from the Fairfax Herald hinted at the backlash to come, calling the nomination a gateway to “negro justices, and negroes for all the other offices … If you are opposed to negro rule,” the editors intoned, “you should not only vote against the negro candidate, but against all the Republican nominees…” A white candidate was elected.[27]

As such alarmism gained ascendance alongside Lost Cause ideology, the revision of Virginia’s constitution in 1902 to systemically suppress Black votes helped solidify the southern-leaning Democratic Party in Fairfax.[28] By 1915, Klan recruitment was proceeding apace, spurred by blandishments like free showings in Herndon of the blockbuster white-supremacist film, Birth of a Nation. [29] Prominent Falls Church educator and Black community leader Edwin B. Henderson told an NAACP interviewer that he had been obliged to obtain an unlisted phone number about that time, after receiving repeated phone threats and “over a hundred vile and threatening letters” from the Klan (anonymously signed “K.K.K” and too disturbing to reproduce here).[30]

Fairfax historian Patrick Reed described this early 20th century Fairfax as a polity that "remained stable as long as blacks remained satisfied at the bottom of the social, economic, and political ladder.” In the wake of racial protests in 1917 at northern factories going full tilt to meet wartime needs, Reed writes, the Fairfax Herald smugly “suggested that ‘the negroes should learn from this that their truest and best friends are the Southern people, who understand their weaknesses and limitations.’”[31]

On top of economic insults, threats, and casual disdain, Black Ildans would have lived with the constant threat of race violence. Theorist Marisa Fuentes writes that violence “disappears” Black people, physically but also from the historic record.[32] This effect, too, helps understand the fading of Black Ilda.

On a map of 90 lynchings known to been committed in Virginia from 1880 to 1926, the atrocities clearly cluster to the south, but Black Northern Virginians certainly knew the fear of race violence. Fear would have radiated in Ilda households on hearing news from Leesburg of the extrajudicial killings of schoolboy Orion Anderson in 1889, for the crime of frightening a white girl (on Halloween, as it happened -- a childish prank?) and of farm laborer Charles Craven, in 1902. Nearer still, in Alexandria, Joseph McCoy was executed for allegedly "outraging" the daughters of his white employer, and in 1889, 16-year-old Benjamin Thomas was murdered for an alleged offense against a white girl. This was the same Alexandria where, in the 1920s and '30s, young Viola Johnson Richardson still would know to min Id her p's and q's. While not personally subjected to race violence, Richardson surmised her parents had experienced that fear, while she herself sensed the constant need to, "know our place... I know I was afraid to go anyplace where I knew that the Black weren't allowed to go. Because when I went to Alexandria, I knew where I was supposed to go," for theaters or dining, and when entering restaurants, knew "I had to go in the back. "[33]

Might the parents of Black Ilda have advised their own children to leave? Most did move away. Tax rolls tell us the Gibsons' son Wesley (who would later live in Southwest D.C.) was paying taxes as early as 1894 on two acres his father owned in Merrifield: Did his parents set him up there, in the heart of a strong Black community, as an alternative to Ilda? Strother Gibson seems to have the only member of the founders' second generation to have stayed local into old age, building a log home off Braddock Road for his large family and working for the prominent white Willard family of Herndon.[34]

Mapping Ilda's Diaspora

Ilda's founding families lasted there barely two generations. This map shows some of the places where they and their descendants lived after leaving the Gibson-Parker community. (Click a node to see biographical details.)

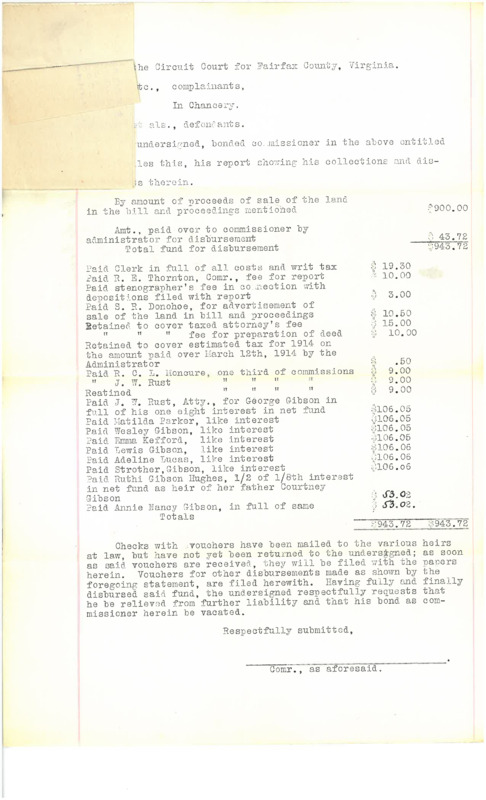

When Horace died a widower, his property was meted equally in eight parts to nine descendants (including two grandchildren each receiving a one-sixteenth share) of a little over $100 each.[35] We cannot know what the Gibsons and Parkers would have reaped at Ilda had they found it more hospitable and been able to stay longer on the land, but we can look at comparative examples that hint at the opportunity costs of losing the right to remain. The first loss comes from market timing, or the lack of it, really. The early 1900s were not a propitious time to sell Fairfax land yet, as Horace’s executor, Strother Gibson seemingly was compelled to, presumably to mete out the inheritance. Values had actually declined since right after the Civil War, when assessments averaged approximately $17.00 per acre. Gibson had paid $30 each for his original five-acre stake in 1868. A 1902 sale of land purchased around the same time by Moses Parker and family friend Robert Williams (who left his estate to the Parker children) fetched only $65 for just over three acres, another indicator of Fairfax farmland's low value at the turn of the century.[36] Consider for comparison that the poll tax that year was $1.50.

Residents of The Pines, displaced by the county iin 1964, were also denied a chance to time their sales; even worse, because the county took their land under eminent domain, they had no option to negotiated the price. Five generations dwelling in the secluded community received letters from the County School Board giving them 60 days to sell or accept the county price, so as to make way for a new school (integrated, ironically). Their homes would be demolished as they struggled to obtain first mortgages and find other neighborhoods open to Black residents. The school was never built.[37] Marion R. Dobbins, whose grandmother was one of those forced out, laments the triple whammy of receiving a low price and losing debt-free security while being thrust from a lifelong home and community. “My grandmother, although they had owned the land in the Pines and didn’t have a mortgage and would have been very comfortable in their senior life, then had to go and mortgage to get money enough cause the county did not pay them enough to build another house.”[38]

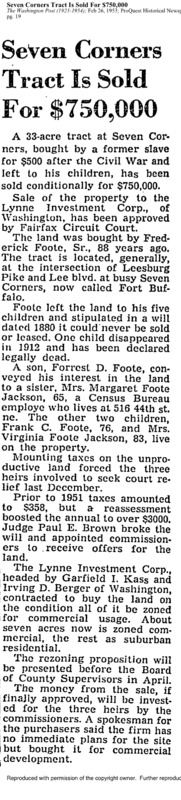

While the “transformation of farms and fields into bedroom communities made Fairfax a site of white prosperity and Black displacement, we do know a handful of Black Fairfax proprietors, at least one of them directly descended from Ilda, reaped windfalls during the mid-century development boom.[39] . Horace Gibson’s great-granddaughter Virginia Williams (a daughter of Strother’s daughter Martha) was covered by the Washington Post for her staunch refusal to sell in the late 1980s. A housing-hungry county government wanted to clear the area where Fairfax City’s Black School Street community had nestled for some 70 years to enable a cluster of luxury townhomes. With its small houses on sometimes large lots, relatives' often living in close proximity, School Street had been a leafy, tight-knit enclave. “If I die and they burn the house down, I’m still going to have this land,” a defiant Williams told the Washington Post in 1989.[40] In 1991, though, she finally did sell to the Fairfax County Redevelopment Authority for $440,000 – a staggeringly high multiple of her forebears’ investments, although possibly still less than the cost of one of the several homes that went up on her property. In Falls Church, meanwhile, Seven Corners and Eden Center would sprawl across a thirty-three-acre parcel of land passed down from formerly enslaved proprietor Frederick Foote.[41]

For most, though, alongside the economic costs of displacement, the loss of family cohesion must have been shattering. As opportunities shrank at Ilda. Moses Parker, Jr., had tried to make a go of farming several acres he inherited from Robert Williams, the friend and adjunct member of his father's household. After just a few years, though, Moses Jr., like many of his siblings, moved to New England, as the map shows. Two Gibson brothers also farmed for several years at Ilda, but in the end, none stayed. [42]

A Black community’s numbers, its timing, the inclinations of white neighbors and elites to help or hinder (or shoot), even the layout of local roads, all could mean the difference in a community’s thriving or dying out. Persistence, of course, was a given for Fairfax's stalwart Black placemakers, as when the First Baptist Church of Merrifield had be start be rebuilt from the ground up after an 1890s storm felled its nearly completed building. Weather, they could face down. Long commutes by foot to church or school, like Viola Richardson’s, would tire but not faze them. They would politic quietly and vote, obstacles be damned, and petition courts and local government for public services as well as justice. But even those that persisted well into the 20th century could be tripped up by nearly implacable contingency. Again and again, Black people in Fairfax would be pressed to yield their right to remain.

[1] Interview with Marion J. Ransell-Dobbins, 2008 (transcript), interview by Byrne, Linda, 2008, 4, Providence District History Project, “Providence Perspective,” https://research.fairfaxcounty.gov/ld.php?content_id=54175404.

[2] Nan Netherton, ed., Fairfax County, Virginia: A History (Fairfax, Va: Fairfax County Board of Supervisors, 1978), 539.

[3] Charles Rinehart, Louis Berger Group, Inc., “Guinea Road Cemetery Study,” 27. For Matilda’s Colored Association service, Badil-Abish, Shades of Gray, 56.

[4] Shoop, “Cornerstones,” 75.

[5] D.Anne A. Evans, Wakefield Chapel (Fairfax, Virginia: Fairfax Office of Comprehensive Planning, 1977), 55.

[6] Evans, 55.

[7] Netherton, Fairfax County, Virginia, 539.

[8] Shoop, “Cornerstones,” 66.

[9] Netherton, Fairfax County, Virginia, 512.

[10] Netherton, 520.

[11] Netherton, 518–19.

[12] Dolores Hayden, Building Suburbia: Green Fields and Urban Growth, 1820-2000, 1st ed. (New York: Pantheon Books, 2003), 27.

[13] Netherton, Fairfax County, Virginia, 521.

[14] Scott E. Casper, “Out of Mount Vernon’s Shadow: Black Landowners in George Washington’s Neighborhood, 1870-1930,” in Beyond Forty Acres and a Mule: African American Landowning Families since Reconstruction (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2012), 47.

[15] Casper, 57.

[16] Netherton, Fairfax County, Virginia, 527-528.

[17] Steadman, Falls Church, by Fence and Fireside., 212.

[18] Netherton, 525.

[19] “Strother Gibson Dead,” Herndon Observer, April 22, 1927, Virginia Room, Fairfax City Library.

[20] Netherton, Fairfax County, Virginia, 529.

[21] John Payne, “Road Petition 267 - W.T. Rumsey,” 1889, Fairfax Circuit Court Historic Records Center. (Ilda descendants, including Howard and Badil-Abish credited Gibson and Parker with building Prosperity Road. However, road petition records at Fairfax Circuit Court show this to be incorrect.)

[22] Netherton, Fairfax County, Virginia, 528.

[23] “Virginia Memory: Chancery Records Index - 059-1914-043,” accessed March 21, 2023, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=059-1914-043.

[24] Shoop, “Cornerstones,” 83. For “400 acres,” Badil-Abish, Shades of Gray, 38.

[25] Netherton, Fairfax County, Virginia, 534.

[26] Donahue, “Silent Majority and Civil Rights: Evolving Views of ‘Them’ and ‘Us:’ Of Our Own Making,” 139.

[27] Netherton, Fairfax County, Virginia, 446.

[28] Netherton, 471–72.

[29] Netherton, 535.

[30] Local History Collection Mary Riley Styles Public Library, Interview with E.B. Henderson, accessed May 1, 2023, http://100yearsblackfallschurch.org/items/show/272.

[31] Netherton, Fairfax County, Virginia, 508–9.

[32] Marisa J. Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive, Early American Studies (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), vii, https://doi.org/10.9783/9780812293005.

[33] “Racial Terror: Lynching in Virginia |,” accessed May 5, 2023, https://sites.lib.jmu.edu/valynchings/victims/. For Viola's comments, Viola Richardson, Viola Johnson Richardson Oral History, interview by Marion Dobbins, November 22, 2013, https://ethnography.gmu.edu/collections/novacra/viola-richardson, Northern Virginia Civil Rights Archive,

[34] “Strother Gibson Dead,” Herndon Observer, April 22, 1927, Virginia Room, Fairfax City Library.

[35] Matilda Gibson et al vs. Adeline Lucas et al in re Estate of Horace Gibson, No. 1914-043 (Fairfax County Chancery Court March 1914).

[36] Lucy Parker v Page Parker and Julia Parker Carter in re Estate of Robert Williams, No. 059-1902-039 (Fairfax County Circuit Court - In Chancery October 1902).

[37] Fairfax County History Commissioners, “Fairfax County African American History Inventory Draft Report,” 2021, 76, https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/history-commission/sites/history-commission/files/assets/documents/aahi/aahi-report.pdf#page19https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/history-commission/sites/history-commission/files/assets/documents/aahi/aahi-report.pdf#page19.

[38] Dobbins, Interview with Marion J. Ransell-Dobbins, 2008 (transcript), 5.

[39] “Bulldozers, Black Lives, White Suburbs: Removing Earth and Memory · Black Lives Next Door · Legacies,” accessed April 26, 2023, https://research.centerformasonslegacies.com/s/blnd/page/bulldozers.

[40] DeNeen L. Brown, “‘Back to School’ Next to Our University: The History of a Long-Standing Black Community in Fairfax · Black Lives Next Door · Legacies,” The Washington Post, August 14, 1989, https://research.centerformasonslegacies.com/s/blnd/page/-back-to-school-an-in-depth-look-at-the-forgotten-historic-location.

[41] Russ Banham, The Fight for Fairfax: Private Citizens and Public Policymaking, Second edition (Fairfax, Virginia: George Mason University Press, 2020), 19.

[42] Shoop, “Cornerstones,” 68.

Mandy Katz