Ilda - A Model of Black Placemaking

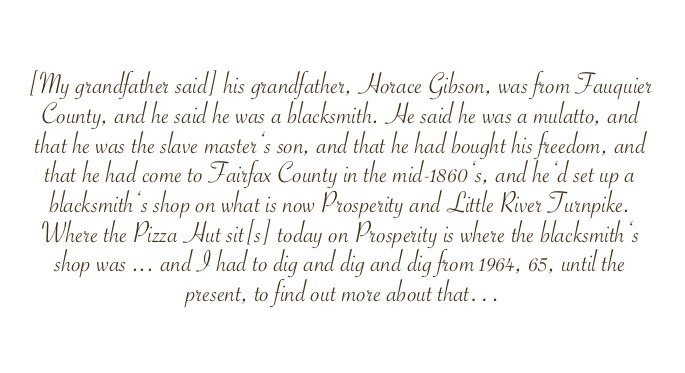

Like Fairfax today, the story of Ilda revolved around traffic and the incessant need to move people and stuff between east and west. Little River Turnpike had been a welcome addition in the early 1800s, as locals needed to get more goods from inland farms to urban markets and ports; exporters in Alexandria were among the road’s first backers, and the highway began there. The 34-mile stretch – (named for a ford at its terminus in Aldie) collected its first tolls in 1806, after ten miles of roadbed had been laid, 50 feet wide and “paved” with pounded stone only down the center. That is where farmer and slaveholder William Gooding, Jr., opened the “ten mile house” tavern one year later, as roadbuilding progressed toward the County Court House.[1] By 1835, the Gooding family had added a blacksmith shop on the highway’s south side – a sound investment, given the rough state of the turnpike and local roads.[2] But the businesses were winding down by the time freedman Horace Gibson arrived from Culpeper County in the mid-1860s. He and his friend Moses Parker could hardly have missed the economic promise of founding their own smith shop to fill the gap.

Gibson, who learned blacksmithing in slavery, perhaps entered the Goodings' still nameless hamlet by working at their shop. Those skills had enabled him to purchase freedom for himself, his wife Margaret (spellings vary) and several children back in Culpeper County, according to descendant Hareem Badil-Abish's meticulous study. The family made their way to this area, “settl[ing] for a time in [a] ‘shanty town’ on Guinea Road on the Old Fitshugh [sic] Plantation.”[3] Gooding’s businesses and, later, Gibson’s and Parker's, sat on or near the spot where Guinea Road met the Turnpike, now State Route 236. Gooding sold the first five acres Gibson bought there in 1868, for $150.[4] Horace Gibson would ultimately hold title to 158 acres at Ilda by the turn of the century, plus two in Merrifield, valued over $8,000.[5] His and Margaret's sons Brook E. and George Henry, in 1889, together bought another 104 acres of Ilda land.[6]

Moses Parker's descendants say he was a wheelwright, a useful skill addition to a blacksmith's offerings. On the 1902 Fairfax voter list, however, he described himself as "farmer." He almost assuredly worked at both. Parker joined his friend Gibson's "start-up" at Ilda in 1869, partnering with a bachelor friend, Robert Williams, to buy six adjacent acres from Gooding for $84. Williams would eventually set up his own home, where his mother would join him, but the 1870 federal census listed him as a member of Moses Parker's household. Occupation: “cook on a schooner.”[7]

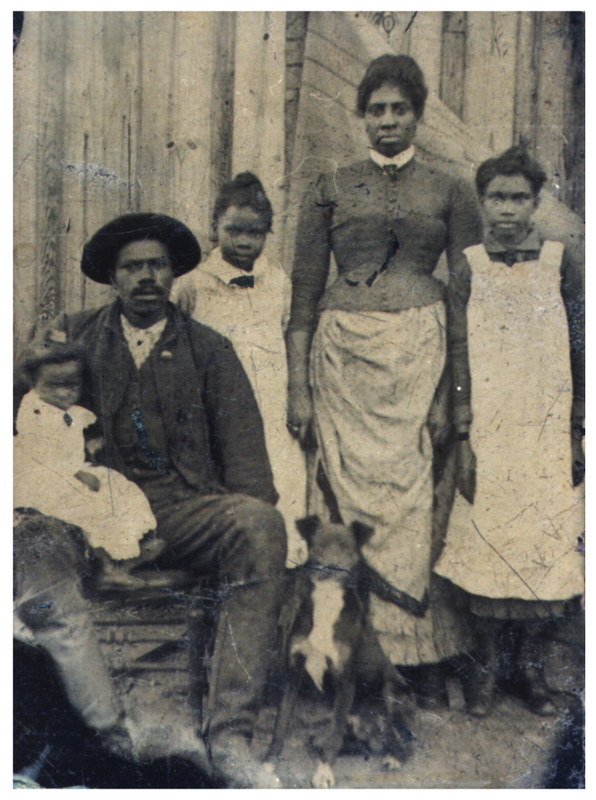

Moses and his wife Emily had nine children: Julia Ann (1854-1921); Page Augustus (b. 1856), who would run the blacksmith shop with wife Matilda Gibson; Mildred (1858-1894); Moses, Jr. (b. 1861); Melinda (1862-1878); Major Stanfield (1865-1892); Robert (1865-1884); James H. (b. 1868); and Mary Louisa (1872-1887). Of Horace and Margaret Gibson’s twelve children, six were born before the move to Fairfax, possibly into slavery: Strother (1846-1927); Adalina (b. 1851); Wesley (1854-1941); Matilda (b. 1859); Brook E. (1862-1897); and Mary (b. 1864). John Edward (b. 1867) may have been born in a shanty on Guinea Road. His younger siblings, George H. and Emily (b. 1868), Lewis (1872-1929), Henry (1871-1872), and Tommie (1874-1874) came into the world as children of proud proprietors of a thriving Fairfax County enterprise.[8] The conjoined grandchildren of this union of business and friendship – through the union of Matilda and Page – numbered nine in all. Many of their siblings had similarly large families.[9]

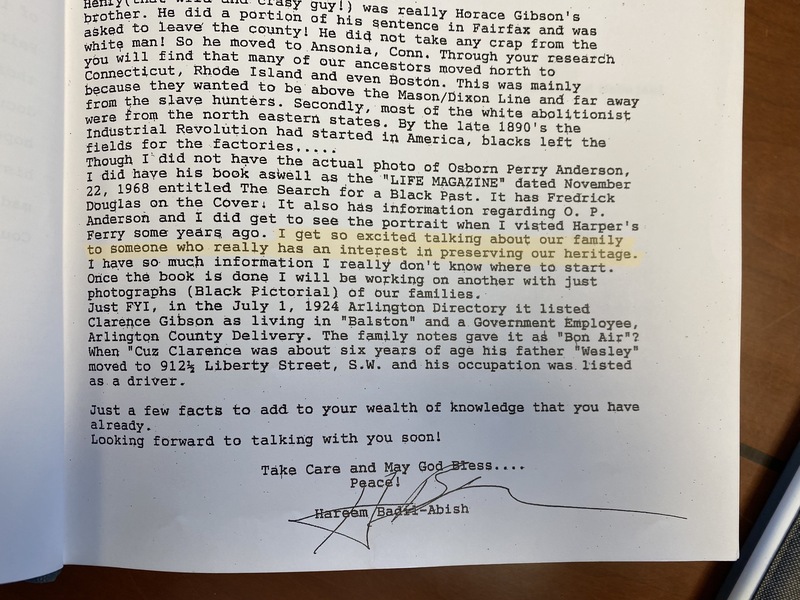

It bears noting here the source of such details, amassed in no official records or yellow-leaved family Bible. They come to us mainly thanks to the doggedness of a Gibson-Parker descendant named Hareem Badil-Abish (1952-1997).[10] Decades before Fairfax County began assembling its African American History Inventory, Badil-Abish had the foresight to learn from family elders who still remembered Ilda and early Black Fairfax. His persistence in cross-referencing their photographs, memorabilia and oral tradition with the documentary record is a prime reason Ilda never really disappeared from memory. After he died, his cousin, Dennis Howard, carried on the work and published Badil-Abish’s manuscript, a trove of genealogy, images and family history: Shades of Gray: A Beginning-- the Origins and Development of a Black Family in Fairfax, Virginia. While not dispositive (historians must always check and amend one another’s work), the book is foundational to an Ilda archive that is now expanding, thanks to the efforts of county historians, Fairfax County Circuit Court archivists, Virginia Room librarians, students like me, and perspicacious and dogged local researchers including journalist-author Tom Shoop and public historian Marion R. Dobbins, a descendant of Merrifield community and church founders. This work rests on their shoulders.

The extended Gooding family, which still controlled more than 300 acres after selling the crossroads to Gibson and Parker, identified their location on tax maps as “Ravensworth,” linking it to the sprawling 17th-century Fitzhugh plantation of that name that once covered 22,000 acres from Fairfax Court House east to Falls Church.[11] (Today, the name lives on in a shopping center along Braddock Road, anchored by Asian grocery store Lotte.)

Whatever they made of the Ravensworth history, the land had its attractions for the Gibsons and Parkers. For one thing, it was cheap, on account of the war. Freedman James Lee, whose name would later adorn schools in Falls Church, described returning to the area from compulsory service as a Confederate trench digger to find “things all torn to pieces. The railroad track was torn up and the ties were bent around trees. No church was open and the state of affairs was dreadful.”[12] Gibson’s $30-per-acre price for the blacksmith site may have reflected its premium location; most local land then and in ensuing decades sold for less.

Gibson might have wanted that particular location for its prominence and its existing connection to a well-known (by then no longer operating) smithy. The Turnpike offered accessibility not just to passing traffic but also to D.C. and Alexandria markets. In later decades, it also connected Black Fairfax to better employment opportunities, private and Federal, in Washington.

In addition to running the blacksmith shop, the Parkers and Gibsons would have farmed for their own uses and perhaps to sell. Most local Black families combined income-producing jobs and businesses with farming at home until well into the 20th century. Viola Johnson Richardson, born in Ilda in 1922, recited a litany of sustenance activities her parents undertook on their 30-acre farm, including harvesting, preserving, canning, hog-slaughtering, and sausage-making, “to last us through the winter.”[13] Descendant Dennis Howard, not born until 1950, recalled farm activity in Black Fairfax households even decades later. Howard describes regularly walking as a child the two miles from his mother’s home in Falls Church to that of his maternal grandparents, Clarence and Sarah Gibson, set on 15 acres on Gallows Road, near what is now Inova Hospital. There, he told an interviewer, they “used to have apples, and used to have pears, and used to have strawberries, and used to have cherries, and used to have grapes. There were blackberries, strawberries, mulberries. He had a farm. He had corn and all kinds of vegetables in his garden. He had pigs. He had rabbits. He had hogs. He had chickens.”[14]

As attractive as cheap land and market access, the newcomers from Culpeper may have found Northern Virginia more hospitable, culturally and racially, than counties to the south, thanks to the pronounced presence of Union veterans, Quakers and other foes of slavery. Some came after the war, but many arrived as early as the 1840s, when plantation-holders were giving up on their land whose value, due to market conditions and tobacco monoculture, had plunged. “Thousands and thousands of acres … were abandoned as worthless, and became covered in a wilderness of pines,” a local recalled.[15] In came farmers and idealists from crowded counties farther north, according to historians Maddy McCoy (founder of the Slavery Inventory Database) and Susan Hellman. “Families from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Maine, and other northern states purchased large tracts of land at rock-bottom prices,” they write. “They streamed into Fairfax County, ready to apply progressive farming practices and a new social agenda.”[16] Whereas some longtime local proprietors (unlike Gooding) refused to sell to African Americans, these Yankee and Quaker farmers were among the prominent boosters of several local Black communities.

Howard proudly described how his two ancestors, still relatively fresh out of slavery, did their part to help the region recover from war’s ravages. “Horace Gibson and Moses Parker … knew each other before they came here. They both were mulattos, they both were the slave master‘s son, they both were blacksmiths. Horace Gibson had hired himself out to the plantation of a William Parker, who was a white slave master,” which would explain, if Moses’ surname came from his enslaver-father’s surname, how they met.[17] Badil-Abish writes that they thrived in Fairfax, becoming “quite successful and prominent in the area, their combined talents as blacksmiths and wheelwrights became well known in and around the courthouse area.”[18] Might they have followed Gooding’s example, if they could, and also opened a tavern to provide another source of revenue while drawing more custom to their shop? We can’t know, but while white people then would let African Americans shoe their horses, few would have patronized a Black-owned hostelry. A white man named Arthur Davis did operate a general store in the area, where he also served as postmaster for ten years in the early 1900s. Did Gibson and Parker consider the question of racial diversity when they came to live at Ilda? Even if they would rather have settled among other Black landowners, majority-Black villages were still scarce in the 1860s, other than those, like Oak Hill, set on plantations where their residents had formerly served in bondage. In any case, the blacksmiths themselves may have taken heart from the economic diversity of their set-up, combining their valuable artisan skills with farming as well as income brought in by the third adult in their compound, Parker's friend Robert Williams. We do not know if Margaret Gibson and Emily Parker also have earned outside income, as many Black wives did, but they would surely have supported the shop and farms. By 1880, Williams’s 65-year-old mother was also living at Ilda.[19]

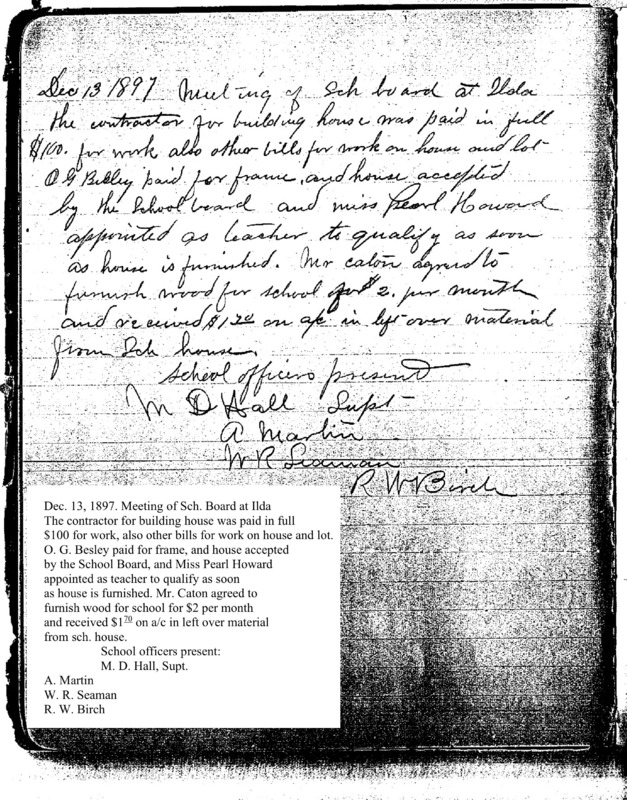

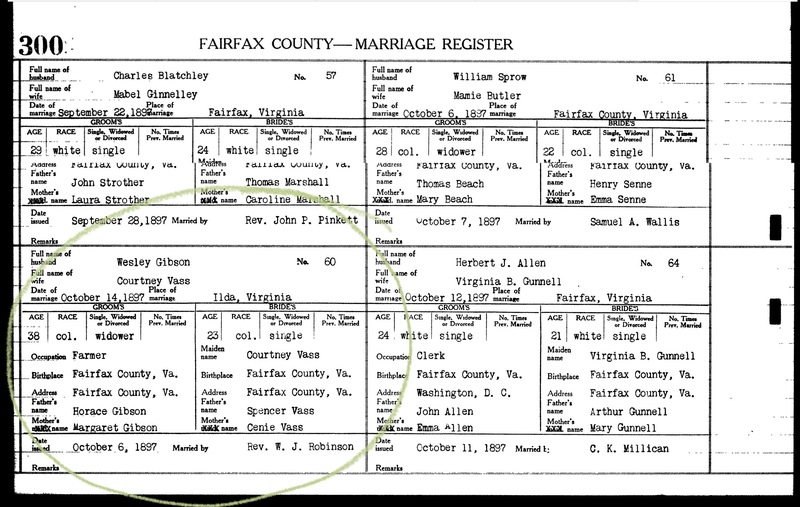

As the new century approached, "Ilda" the multi-family homestead was becoming Ilda the official place. The first reference to Ilda in a legal document so far uncovered came in 1897, on the marriage license of Wesley Gibson and Courtney Vass. In 1903, Arthur Davis, who farmed and ran a general store just up the road from the blacksmith shop, became postmaster of Ilda, marking Federal recognition of the name. [20] In 1915, it appeared for what seems to be the first time on an official U.S. map of Fairfax, created by the U.S. Geological Survey.[21]

[1] John Browne, The Story of Ravensworth: A History of the Ravensworth Landgrant in Fairfax County, Virginia (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2018), 203–4.

[2] Browne, 216.

[3]Hareem Badil-Abish, Shades of Gray: A Beginning-- the Origins and Development of a Black Family in Fairfax, Virginia (Virginia: Estate of Hareem Badil-Abish, 2005), 35. Regarding the road’s name, writes Badil-Abish, ”It is interesting to note that the majority of slaves imported into Virginia came from the West Afican [sic] Country of Guinea by way of the West Indies. Many colored settlements were even called Guinea Towns (pronounced "Ginn-ee") and the blacks were called "Giney's by the white's [sic].” Badil-Abish, 39. Tom Shoop, in his manuscript for Cornerstones: Bias and Burials at an American Crossroads (forthcoming from University of Virginia Press), concurs that the presence of Black dwellings led to the road’s bearing a name that should rightly be considered a slur.(39)

[4] Tom Shoop, “Cornerstones: Bias and Burials at an American Crossroads” (2023), 36.

[5] Badil-Abish, Shades of Gray, 50.

[6] Badil-Abish, 44.

[7] Shoop, “Cornerstones,” 33, 40. Parker family names and ages from Badil-Abish, Shades of Gray, 169.

[8] Badil-Abish, Shades of Gray, 39, for names and birth years; death years added where available from this and other sources.

[9] Badil-Abish, 43.

[10] “Hareem Badil-Abish, ‘United States Social Security Death Index’ • FamilySearch,” accessed April 23, 2023, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:JR8Z-WWT. For Badil Abish’s line of descent, see Shades of Gray, 33.

[11] “Fitzhugh, William (the Immigrant) (1651-1701),” March 30, 2013, https://ravensworthstory.org/people/owners/fitzhugh-family/fitzhugh-william-the-immigrant/.

[12] Marion Dobbins, “Freedmen of Northern Virginia Black Communities and the Northern Virginia Baptist Association” (Fairfax, Va., George Mason University, 2014), 15, https://www.academia.edu/8153029/Freedmen_of_Northern_Virginia_Black_communities_and_the_Northern_Virginia_Baptist_Association.

[13] Viola Richardson, Viola Johnson Richardson Oral History, interview by Marion Dobbins, November 22, 2013, https://ethnography.gmu.edu/collections/novacra/viola-richardson, Northern Virginia Civil Rights Archive, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vhuQ-0SSoDE.

[14] Dennis Howard, Oral History Interview with Dennis Howard, interview by Byrne, Linda, 2005, 822, A Look Back At Braddock Oral History Project, https://research.fairfaxcounty.gov/ld.php?content_id=54175404.

[15] Noel G. Harrison, “Atop an Anvil: The Civilians’ War in Fairfax and Alexandria Counties, April 1861-April 1862,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 106, no. 2 (1998): 133, https://www-jstor-org.mutex.gmu.edu/stable/4249703.

[16] Susan Hellman and Maddy McCoy, “Soil Tilled by Free Men: The Formation of a Free Black Community in Fairfax County, Virginia on JSTOR,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 125, no. 1 (2017): 46, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26322581.

[17] Dennis Howard oral history, 825.

[18] Badil-Abish, Shades of Gray, 36.

[19] Shoop, “Cornerstones,” 46.

[20] “U.S Post Office Department Reports of Site Locations, 1837-1950: Virginia, Dinwiddie - Fairfax” (National Archives, Collected -1950 1897), Record Group 28, NARA Records of the Post Office Dept., https://catalog.archives.gov/id/608210.

[21] Shoop, 45.

Mandy Katz