St. Louis: "How Can We Live Without Water?"

For Black villages and enclaves in western Loudoun County, the effects of the changing landscapes, heightened costs of living, and outcomes of the myth of progress have created constraints on livelihoods. The Village of St. Louis is a microcosm of what slow violence looks like in western Loudoun County. The rising tide of slow violence in Loudoun County that surrounds St. Louis has built up structures that reinforce displacement in place because beyond the slow violence implicated in controlled modernity’s progress, there is a history of environmental and structural inequalities that have further harmed St. Louis, specifically access to water and water infrastructure. These problems have only been exacerbated in the last five years as St. Louis has begun to deal with the presage of large-scale housing development in their community.

Displacement in Place in St. Louis

Like Gum Springs and Tinner Hill in Fairfax County, St. Louis is a Black community that has existed since at least the later decades of the nineteenth-century. The largest Black village in Loudoun County, St. Louis, has grown and expanded over generations with historic ties to the land and the white communities around them – particularly Middleburg – both through the post-emancipation period and throughout the twentieth-century. As the largest communities of western Loudoun have grown and modernized over the previous half-century, many of the smallest communities have not. Water and infrastructure have long been lacking in many of these communities. Reliance on well water is common in the west, and it is the only way to source water for St. Louis. However, for St. Louis, the water table is low, making it hard for the residents to source water. Often in the past this has driven residents to have to walk miles to gather water by buckets. In the case of St. Louis residents Cristelle Hughes and her daughter Carolyn Grayson, both recalled in a 2022 interview that even after Cristelle and her daughter had moved from St. Louis in 1964, family members drove to gather water in 10-gallon tanks – and at times Cristelle would have to walk onto white owned land to gather water in buckets.[1] Carolyn remembered capturing rain water from the roof to wash the family’s clothing with, while Cristelle later noted that “Half the time you bought water to wash your clothes.”[2]

Access to water and clean water systems through wells continues to be tedious for many St. Louis residents. Long-time and multigenerational Black residents have been forced to dig multiple wells on their properties. This is both because the land upon which they live has poor percolation and low water tables, but also because as more wells have been dug, water “comes up short.”[3] This has been a growing issue for the community. As more residents move in during this time of rising populations and development, water table levels declined, thus further exacerbating the water access, particularly for the remaining long-time Black residents with old wells. At a June 9, 2021 County Board of Supervisors hearing on the development plan for the 16-acre Middleburg Preserve II (MP-II) development owned by MOJAX LLC in St. Louis (later discussed in this section and the third part “The St. Louis Village Task Force and Loudoun's Conservation Culture”) multigenerational Black resident and land owner John Holmes remarked the troubles of accessing water in St. Louis, and the impact of development and water usage:

“Since the home I’m living I, I have bored two wells. The first well I had? I would pray that it rained. No water whatsoever. If it don’t rain for about two or three weeks? We don’t have no water… You couldn’t flush your stools or couldn’t do nothing. And since I’ve been in this home, I had two filtration systems put in from the rust, sulfur gas, all kinds of particles in it, stuff like that. And my main concern is about the senior citizens of St. Louis, that they had their homes passed down from their ancestors and stuff like that…They can’t go outside over the tops of their wells and pour chlorine in the tanks, stuff like that? I mean what use is it? They can’t even afford a filtration system…

What are we going to do about all the drainage we have with St. Louis. If it rains, some of our front yards, back yards, they like a swamp. So if you build up more houses, what’s that going to do? Their water drains into my yard? Maybe someone else yards?”[4]

Mr. Holmes highlights the troubles of trying to maintain access to water in St. Louis due to the poor infrastructure and overreliance on wells and two more issues. Not only is the water table low, but the water is full of particles and minerals that are unsafe to consume, and on top of this drainage has been a severe issue creating further environmental and health threats.

For most residents of St. Louis, access to potable water forces them to use filtration systems. High amounts of minerals and particles mean that without this, their well water is often unsafe, and these filtration systems come at a steep price. Yet, as John Holmes pointed out above, the filtration systems struggle to keep up with the problem. Mary Howard, an elder resident of St. Louis, and Laverne “Tootie” Warner, a resident of St. Louis both spoke of the poor quality of water in St. Louis:

“Dr. Wendi Manuel-Scott:

Right. So yeah, I was hearing about the water last week so help me understand the water situation?

Mary Howard:

The water is hard, here in St. Louis. It’s not real good water. You know, and then you use so little it rusts you know.

Dr. Wendi Manuel-Scott:

It’ll rust?

Mary Howard:

I mean, you-, your faucet and things rust.

Tootie:

All the iron and sediment and stuff in it. And it turns everything-, if you-, if you wash your clothes-

Dr. Wendi Manuel-Scott:

It’ll turn yellow.

Tootie:

Yeah it turns that really rest color yellow, you know whites and stuff and that’s all in your, it’ll get in your toilets, it gets in your washing machine and tub thing, um, and yeah…

Dr. Wendi Manuel-Scott:

Oh so it’s hard on appliances I bet.

Tootie:

Yeah. Yeah, it is. It’s really hard on anything cuz it makes peoples dishwashers and things like that um, unusable.”[5]

For the community of St. Louis water has been an issue and remains an issue. Their water's safety is questionable, filled with minerals and particles that are unsafe to consume, and the residents rely on expensive filtration systems that require maintenance. Returning to the June 9, 2021 Board of Supervisors meeting, local resident Sean Clancy read quotes of community members expressing their fear of what would be lost upon further expansion, and the troubles of accessing clean water already:

“We have extensive and expensive water treatment equipment in our home, and already the parts are failing. Even after the water passes through the equipment it smells and is cloudy. We filter it again before drinking or using it for cooking. How can we live without water?”[6]

The intersection of lacking infrastructure and poor water quality points to environmental racism in St. Louis. Whether intentional or not, St. Louis has been neglected to improve the situation in St. Louis and has left both new and old residents with a situation where their water is both at risk of neither being potable nor accessible. In 2019, the Loudoun Environment Health Manager George Khan even recognized the County's failure to address this issue, one they state has long been known. Yet, according to Khan, the County “hasn’t wanted to spend the time and effort to mitigate the quality issues.”[7]

These problems in St. Louis are only furthered by the rising potential of development in the community, something that threatens the balance of a long-struggling community. Upon the announcement of MOJAX LLC’s plan to develop anywhere from 9 to 30 homes in St. Louis, the likelihood that there would ever be enough water for the community's original residents became a possibility. While other western localities, such as Middleburg and Purcellville have moved off of well reliance onto public water in the previous four decades, St. Louis has maintained its reliance on wells for water access, the County saw it fit enough to be moved onto public sewerage in 1981,[8] however, not public water for no apparent reason.[9]

Physical Displacement in St. Louis

The ever-increasing pressures on the Black community of St. Louis highlights slow violence and displacement in place as decades of poor water quality and inability to access water regularly put severe constraints on the livelihoods of its Black residents. Combined with increased development pressures, and the influx of new residents in the past two decades – discussed briefly in the previous section – means the already shrinking community is further displaced in place. With the risks posed by changes such as MOJAX LLC’s proposed developments in the community, this has meant rising taxes, the loss of affordability for low income, elderly Black residents, and the physical displacement of those remaining.

While land might be viewed as affordable to those who seek to move into the area, for generational landowner’s increased tax burdens and costs of living have become a problem. Many of those remaining Black community members are elderly, and as such income is low or fixed and due to rising costs of living, many have had to leave or are unable to keep the land. Many of them are also skeptical of those who move into the community, as Carolyn Grayson in an aforementioned 2022 interview stated:

“Carolyn Grayson:

I understand that because um, a lot of the land has been sold. The land of the, that the black people owned and, and to be honest with you, the white people see it as a…

Dr. Wendi Manuel-Scott:

Yes

Carolyn Grayson:

They're going to turn it into something.”[10]

This problem doesn’t just affect elderly community members though, as some community members in the previous two or more decades have recognized the growing pressures of development in the region. In a 2022 interview, St. Louis resident Sharon Peterson tells the story of needing to sell land that had been in the family for multiple generations:

“I guess, you know you sell little bits to sell taxes. I’m not sure, I didn’t understand then, because when I bought it back, I had-, well when my mother died, uh it was 6 acres and a house and I was so- I hate to tell this story, I was so frustrated with my sibling until I almost gave it away. I almost sold it, because I had been paying taxes on two different for 15 years, I couldn’t, I tell them I couldn’t afford it. So, I got angry and I sold it. I hate to tell it, that I sold it. But I’m gonna tell it, I sold it for $50,000. Oh yeah. I gave it away…

To buy back cost me half a million, for-, and you haven’t heard the worst part, for little over half an acre.”[11]

Sharon Peterson’s experience shows the damaging effects of the myth of progress, and slow violence on rural Black communities. Like Gum Springs’ experience with displacement during the housing hygiene crisis, when families were displaced due to eviction mandates, generational land was lost and many families were not able to return. Sharon Peterson’s case is a rare situation where someone was able to buy back land albeit at a heavily reduced size. For others who feel regret upon the loss of land, return is likely more of a struggle now than when Sharon Peterson returned to St. Louis as land prices have only risen. Like Gum Springs has endured with the Holland Court development in the past decade, development in the form of the Middleburg Preserve I and II on former Howard Family land left the door open for further dispossession, higher tax rates, and further loss of water inside St. Louis.

MOJAX LLC and Displacement

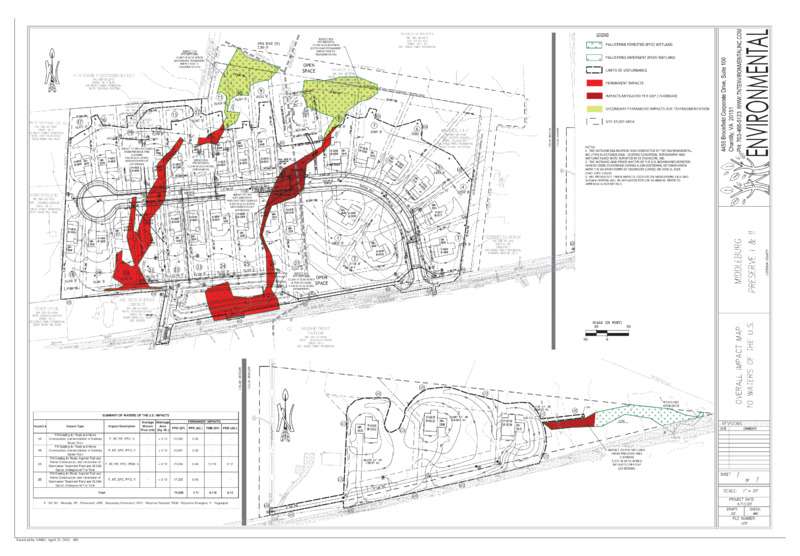

As briefly discussed before, the Middleburg Preserve properties were a development spanning anywhere from 9 to 30 homes on more than 19 acres over two separate sections, comprising four plots of land, including a plot with a multi-family cemetery containing more than 20 graves. The leading development, Middelburg Preserve II was bought by MOJAX LLC (MOJAX) for over $1,500,000[12] and was planned to hold the majority of the homes with a minimum of 9, and the final goal being 27 – built in groups of 9.[13] For a community as small as St. Louis, the thought of adding 27 homes (as well as 3 more in Middleburg Preserve I) was unthinkable to many of its residents. In a community that already struggles with water quality and access, the addition of 9 homes was quickly seen as a danger to the community and left them wondering how such a development was allowed.

Even though zoning restrictions by the County for the western two-thirds of the state existed, cluster developments still allowed developments of that size to exist. The historic Village Conservation Overlay District as part of the County’s Comprehensive Plan currently does not control for development density, and only “provides standards for setbacks, yard requirements, building orientation, sidewalks placement among others, to ensure new development within and adjacent to the Rural Historic Village boundary mimics historic village development patterns.”[14] Even more important was the fact that the development was “by-right,” another piece of the puzzle that gave MOJAX the ability to establish cluster developments with little discretionary scrutiny as long as they followed the zoning and building codes laid out by the County, and acquire the proper permits to proceed.[15] While scrutiny in the permit process opened spaces to oppose building, MOJAX was given a more considerable amount of freedom in the building process.

This points to the failure of controlled modernity’s aims of stifling the myth of progress, as it appears to have only been perpetuated. Not only did it leave room for development on lands containing familial graves, it left the door open for further detriment to Black geographies and their environment. Slow violence and displacement in place had surrounded St. Louis for decades, and in the previous three decades physical displacement grew as familial lands were lost and sold for various reasons. With MOJAX’s Middleburg Preserve plan, it looked like the last straw for many remaining residents. Yet, in the face of the looming development, the whole of the St. Louis community came together in opposition. With clear leadership roles held by the Black residents of St. Louis, the community took to the Loudoun County government for an answer. With the help of local self-described conservationist Chuck Kuhn of JK Movers and JK Land Holdings, the community potentially resisted predatory development for years to come.

[1] Interview with Cristelle Shorts Hughes, interview by Wendi Manuel Scott, Audio Interview, June 2022, Center for Mason Legacies: 49-50.

[2] Ibid, 50.

[3] Ibid, 49.

[4] “June 9, 2021 Loudoun County Board of Supervisors Special Business Meeting,” June 9, 2021, https://loudoun.granicus.com/player/clip/6694?meta_id=195377: 01:13:00-01:15:10 – John Holmes speaking to the Board of Supervisors for public input on land use planning in St. Louis.

[5] Interview With Mary Howard, interview by Wendi Manuel Scott, Audio Interview, June 2022, Center for Mason Legacies: 60-61.

[6] “June 9, 2021 Loudoun County Board of Supervisors Special Business Meeting,” June 9, 2021, https://loudoun.granicus.com/player/clip/6694?meta_id=195377: 00:52:40-00:53:00 – Sean Clancy quoting Bill Baker of St. Louis to the Board of Supervisors for public input on land use planning in St. Louis.

[7] “St. Louis Residents Concerned Development Would Endanger Water, Graves,” LoudounNow.com, September 13, 2019, https://www.loudounnow.com/archives/st-louis-residents-concerned-development-would-endanger-water-graves/article_56f0ebbb-b95b-5021-b115-7eb9f0419440.html.

[8] Eugene M. Scheel, The History of Middleburg and Vicinity: Honoring the 200th Anniversary of the Town 1787-1987. (Middleburg, VA: Middleburg Bicentennial Committee, 1987): 161.

[9] St. Louis Village Plan Task Force, “Draft of the St. Louis Village Plan” (Loudoun County, January 8, 2024), https://www.loudoun.gov/DocumentCenter/View/188680/Draft-St-Louis-Village-Plan-01-08-24: 28.

[10] Interview with Cristelle Shorts Hughes, interview by Wendi Manuel Scott, Audio Interview, June 2022, Center for Mason Legacies: 19.

[11] Interview with Sharon Peterson, interview by Wendi Manuel Scott, Audio Interview, June 2022, Center for Mason Legacies: 11-12.

[12] “Conveyance and Interim Lease of Approximately 6.31 Acres of County Property to Aldie Community Development Company, LLC” (Loudoun County Board of Supervisors, January 13, 2021), https://loudoun.granicus.com/MetaViewer.php?view_id=77&clip_id=6520&meta_id=188011.

[13] “ZONING EXAMPLE INPUT: Rural Historic Village – St. Louis Proposed 27 House Development - Middleburg Preserve” (Loudoun County Preservation and Conservation Coalition, May 4, 2020), https://loudouncoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/LCPCC-Chronology-St.-Louis-5-4-2020.pdf; “June 9, 2021 Loudoun County Board of Supervisors Special Business Meeting,” June 9, 2021, https://loudoun.granicus.com/player/clip/6694?meta_id=195377.

[14] St. Louis Village Plan Task Force, “Draft of the St. Louis Village Plan” (Loudoun County, January 8, 2024), https://www.loudoun.gov/DocumentCenter/View/188680/Draft-St-Louis-Village-Plan-01-08-24: 20.

[15] “What Is By-Right Development?,” Planetizen, https://www.planetizen.com/definition/right-development.