St. Louis: The St. Louis Village Task Force and Loudoun’s Conservation Culture

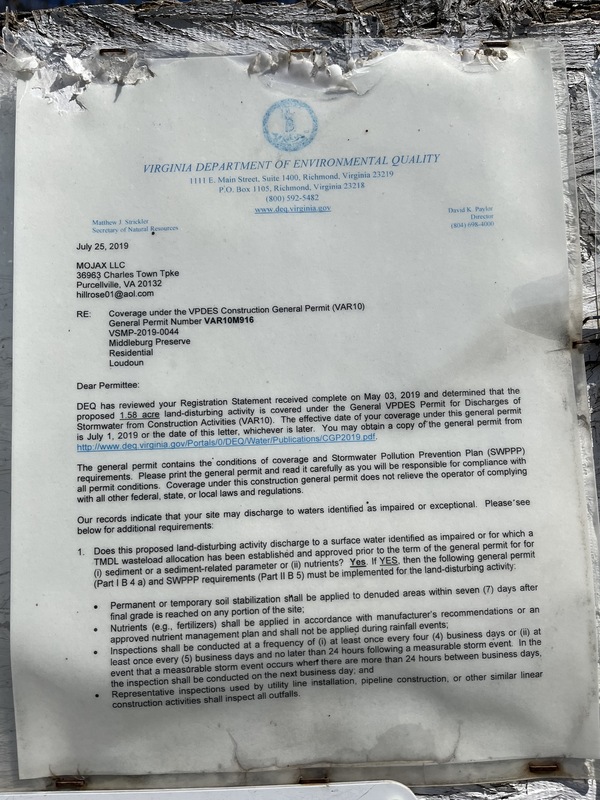

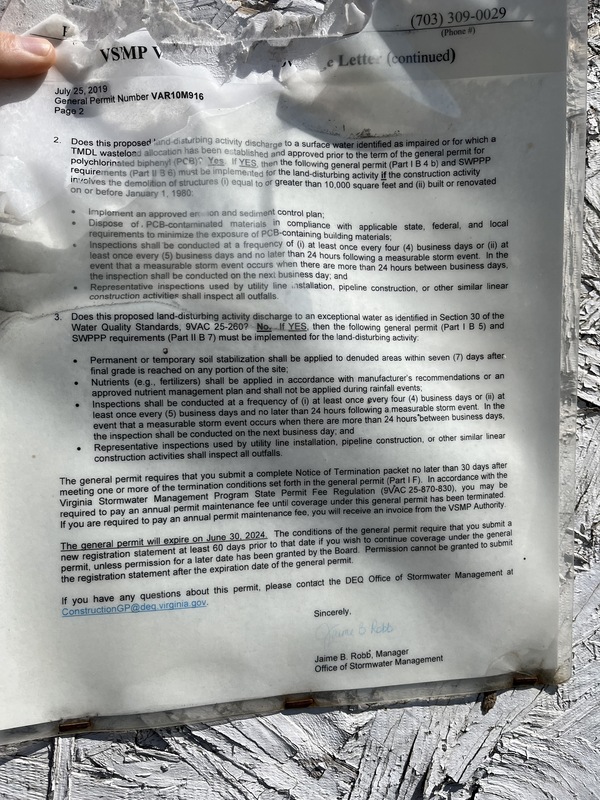

When MOJAX began the process of developing the Middleburg Preserve project in early 2018, the community of St. Louis jumped to action to oppose any work being done. As a by-right development, while having little scrutiny in the building process, permits to begin work were still required. As shown by the Loudoun County Preservation and Conservation Coalition’s report on the Middleburg Preserve development, MOJAX began work clearing land in January 2018 without permits, even though the site of MP-II contained wetlands and the historic cemetery with over 30 graves yet to be identified.[1]

Community Resistance and the St. Louis Village Plan

At the heart of the concern was the environmental danger a development of the size and scope the Middleburg Preserve would pose to both water quality and supply, as well as the fear of raising tax rates and increased traffic.[2] Groups like Friends of St. Louis, the Loudoun County Preservation and Conservation Coalition, Virginia Piedmont Heritage Area, the Unison Preservation Society, and the Piedmont Environmental Council all spoke out over the coming years in favor of protecting and preserving St. Louis, aiding in the process of opposition. As the community sought to oppose this project, the quickest route was contacting Loudoun County officials with documentation and complaints.

Important to note is that both new more affluent and predominately white residents and older, more intergenerational Black residents voiced their opposition to the development. Fears of losing the pockets of affordable housing in western Loudoun many of the newer arrivals, those who had moved in over the previous decade voiced their opposition due to the potential of losing the small town and historic feeling of the community.[3] Coalition between these two groups, new and existing multigenerational Black residents allowed for a more significant response. However, the likelihood that development was even viewed as possible in the community is likely because of the arrival of new residents over the past decades. With the arrival of more affluent residents, they perpetuated the myth of progress and took part in displacement, whether they understood it or not.

Over the next year and a half, the community of St. Louis watched a back-and-forth process occur between Loudoun County and MOJAX as development primarily stalled out as permits and environmental investigations took place. A breakthrough for community action took place in September 2019 – when Board of Supervisors Chair, Phyllis Randall, met with the St. Louis community members at the St. Louis Fellowship Hall of the Mt. Zion Baptist Church. At this meeting Chairwoman Randall announced her stance on the issue – “‘Let me be as clear as possible—I don’t want this to happen… Were it up to me, I would never approve an application [for development] in St. Louis.’” Randall’s opposition to MOJAX’s development opened the door for more focused opposition by the community. Over the next year, Randall and fellow Board member Tony Buffington called for a Board Member Initiative to create a community-led plan of action.[4]

While the rumblings of a community-led plan of action were occurring, the Board of Supervisors sought a way forward with MOJAX to end the development and move towards conservation of the plots of land. While plans pointed to the County buying the by-right development and making the land into a park space, this plan did hit opposition from the Board of Supervisors. MOJAX had sought three times the price they bought the land for, and a trade of land for space in Aldie, a community to east of St. Louis, past Middleburg.[5] While these plans eventually fell through and no actions took place, the push by the community in the early stages of development had driven the Board of Supervisors to stop the project in its tracks.

Turning back to the community-led action plan, in Fall of 2021 the Board of Supervisors began the process of moving towards a St. Louis Village Plan, and by January 18, 2022, the board of Supervisors approved the plan initiating a General Plan policy direction for St. Louis. The St. Louis Village Plan resulted from the St. Louis community, and the County Board of Supervisors. This village plan sets out guidelines to “create a policy framework to address land use and infrastructure issues in this rural historic village that has experienced underrepresentation and has reached a critical moment of change.”[6] As well as aiming to improve zoning and land use in St. Louis, the plan provides for a Water Feasibility Study led by the County to inspect the status of water in the community and “potential methods of providing water and/or wastewater solutions to communities, the projected costs, and the extent of work necessary to implement those solutions.”[7]

Comprised of a nine-member advisory body, approved by Board of Supervisor members, the village plan’s leadership included three crucial Black leaders in the community – Marcus Randolph Howard (whose family’s ancestral lands were the space of the original MP-II development), Laverne Tootie Warner, and Sharon Peterson.[8] The process of implementing the St. Louis Village plan is ongoing, with a hearing by the Loudoun County Planning Commission for public comment on the draft plan held on March 26, 2024. If the Planning Commission approves of the final draft in the coming months of 2024, the village plan will move into place and amend the County’s comprehensive plan, and with luck protect the community for decades to come.

JK Land Holdings, Chuck Kuhns and Middleburg Preserve

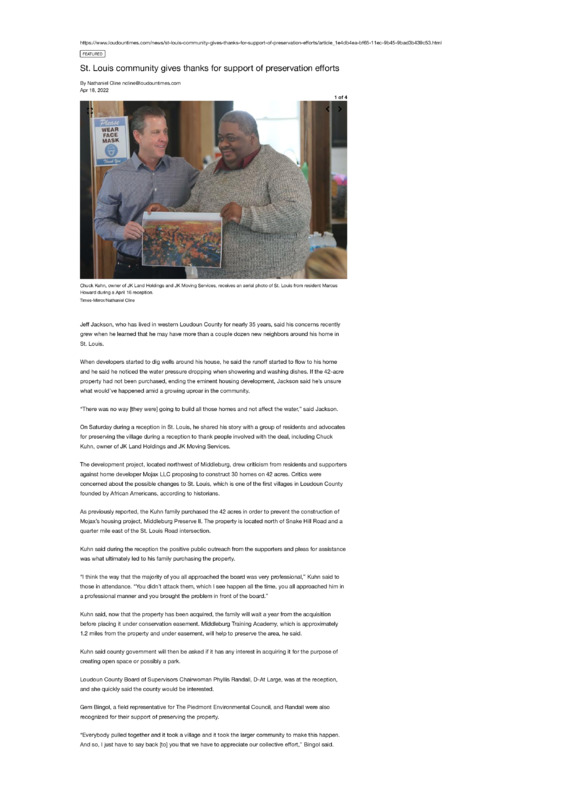

While the County Board of Supervisors sought a way to relieve St. Louis of MOJAX’s development throughout 2021 – with floated ideas of the purchase of land and the eventual conservation of the space – local conservationist and businessman, Chuck Kuhns of JK Movers and JK Land Holdings approached MOJAX with an offer. By November 2021, Kuhns/JK Land Holdings and MOJAX had reached a deal. The Kuhns family put a contract on 42-acres of land in St. Louis including the Middleburg Preserve to prevent the development on the Middleburg Preserve land.[9] The stated intent from the start has been to place the 42 acres into a conservation easement, with the process of conserving the land initially slated to begin following a year of owning the property – and mandatory rule by the County. In total this land would have held 45 newly developed homes, thus in the other land outside of the 19 acres of the Middleburg Preserve the plan was 15 other homes to be built by a development company.[10] Hopefully, peace would return to St. Louis with the end of the Middleburg Preserve development saga.

JK Land Holdings, and the Kuhns family, according to Antonio Olivo of the Washington Post, are “both the county’s largest private land owner and its most active player in the conservation easement program.”[11] In JK Land Holdings’ own words, “JKLH has strategically redeployed more than 22,000 acres of its purchases into conservation easement, ensuring vulnerable vistas and habitats are preserved and protected for future generations.”[12] According to their own creed, they aim to place around 44 acres into conservation for every 1 acre they develop commercially.[13]

The ambitions of JK Land Holdings are admirable, and follow the outlined ideas of controlled modernity as discussed in the first section – the goal of protecting land and environment in the west to retain a landscape being lost in Loudoun. However, the darker side of the use of conservation easements are still potentially at play, even if the goals of the program are done in earnest. The purchase of 42 acres of St. Louis’ land and the acquisition of over 20,000 still act as massive tax gains, and both the tax benefits and the constant acquisition of land in Loudoun County begs questions of how land acquisition perpetuates the cycles that follow the myth of progress, and an inquiry into how JK Land Holdings may in fact perpetuate harms that have been experienced for other Southern Black communities on the behalf of cultures of conservation similar to Loudoun’s.

Culture of Conservation

The community of St. Louis rightfully celebrated their efforts in seeking help, attaining power, and gaining a partner in stopping the MOJAX. The 42 acres of land in St. Louis have sat now, as of the time of writing in Spring 2024, for over two years under contract of JK Land Holdings, as it was purchased in November 2021. While land purchased must be held for a year before being placed in conservation easement according to Loudoun County’s rules, but they have passed that point twice.[14] Thus, question marks remain as to when the land will be put into conservation easement. The last public update was delivered by JK Land Holdings on their website as a sidenote in a different story of 850 acres (about the area of Central Park in New York City) donated by the Kuhns family to be placed into easement by Old Dominion Land Conservancy – a large conservancy that aims to protect land and water with many easements throughout the County including near St. Louis. As of June 15, 2022, this update is the most recent news, as St. Louis waits for the land to be conserved.[15]

The culture of conservation that is part of Loudoun County’s controlled modernity approach to development and maintaining the idyllic landscape (discussed in the first part, “Controlled Modernity – Conservation as Progress”) leaves open questions to its ability to stop the myth of progresses pernicious approach to expansion and development. More specifically, the culture of conservation that makes up the second half of the County’s approach has clear potential to perpetuate dangerous habits of land acquisition and monopolization that displace and dispossess Black communities and mimic plantation geographies. This is not to say all conservation work done by those in Loudoun County, or the aims of the Loudoun County government are pernicious. In fact, as noted in part 1, much of this work to preserve the characteristics of western Loudoun through controlled modernity is done in earnest.

Much like the County’s attempts to control the myth of progress and the development of the east from spanning west, what Kuhns and JK Land Holdings’ work is intended for may be done in earnest and it attempts to maintain land from being lost, particularly in a community like St. Louis displaced in place. However, the ambition to gain tax benefits by having significant land holdings appears to sit at the forefront of large conservationist's minds when considering what to conserve.

When the County sought to change zoning rules, limiting the use of prime agricultural soil thereby effectively reducing the amount of homes on a potential site of development, Kuhns specifically addressed this as a barrier to tax benefits and that JK Land holdings would be willing to walk away from their contracts. Kuhns states he has around “3,600 acres that are under contract, with the intention of buying and placing [these acres] into conservation easement… If these rules are passed, we will walk away from those contracts. We [would] also no longer pursue conservation easements in Loudoun County, Virginia.”[16] As St. Louis is still under contract and yet to be conserved, likely, their 42 acres are included in this. For JK Land Holdings and Chuck Kuhns, the intent is there to conserve land, and maintain Loudoun’s character and landscapes. Yet, it is also clear that tax benefits are very important to this project of conservation and controlled modernity as they are willing to hinge their potential easements upon them.

As acknowledged before, these landholders that are seeking conservation are primarily large LLC’s and rarely are they small landholders and family farms/homes. Nearly “half of the tax credit deals that are happening in Virginia are happening through some kind of LLC or entity as opposed to an individual directly claiming it.”[17] This creates a similar problematic structure where colonial acquisition and monopolization of land is situated in the hands of white landowners, who control what occurs on this land.[18] In a community like St. Louis, who is still waiting for conservation easements to happen, the land has already slipped out of the community’s hands, however the conservation easement would at least keep it from being developed.

While the myth of progress created an untenable situation for St. Louis, the Village turned to the County and developed a way forward to try and conserve their community by law and this process is working out. With the help of JK Land Holdings the land was bought from MOJAX and has staved off development for now, but this situation is still fluid. As it stands, St. Louis is nearly surrounded by conservation easements, with the likelihood that the MP-II land on Snake Hill Road will be joining the large number of easements in the area. Though the land can be conserved to a certain extent – potentially opened for public park access or a different purpose, a white affluent landowner still possesses land that had long been in the hands of the Black community, one with a historic cemetery upon it. The decision of what to do next comes at JK Land Holdings and Old Dominion Land Conservancy’s behest, and progress has not yet been made. This does not mean that conservation is intended to do harm. Instead, this analysis is intended to ask questions of goals in conservation, and whether Loudoun’s culture of conservation masks harms, perpetuates land monopolization, and exacerbates slow violence.

The reminders of MOJAX’s attempts at development remain in St. Louis. As the land waits to be conserved signs of waivers with stop work orders, and posters from MOJAX remain where MP-II was being developed. But the remnants of MOJAX should not undersell the efforts of the community of St. Louis, particularly the patient and perseverant Black community who have dealt with slow violence for generations. Their efforts to gather the full community’s support in resistance to MOJAX and turn to the County for help achieved a positive response. The help of the County resulted in the St. Louis Village Plan Task Force which has worked diligently under the combined leadership of the community, and leading Black residents to carve a way towards a better, and hopefully, more equitable future for St. Louis. On the other hand, the potential conservation easement on the 42 acres of land in St. Louis held by JK Land Holdings lies in waiting. Questions should be asked about the future of Loudoun County under the structures of controlled modernity, particularly the ability for rural zoning, and conservation easements to both support an equitable future and maintain sprawl.

[1] “ZONING EXAMPLE INPUT: Rural Historic Village – St. Louis Proposed 27 House Development - Middleburg Preserve” (Loudoun County Preservation and Conservation Coalition, May 4, 2020), https://loudouncoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/LCPCC-Chronology-St.-Louis-5-4-2020.pdf: 2; Cindy Sabato, “Standing with St. Louis...And Now Aldie,” The Piedmont Environmental Council (blog), December 14, 2020, https://www.pecva.org/resources/publications/piedmont-view/standing-with-st-louis-and-now-aldie/.

[2] St. Louis Village Plan Task Force, “Draft of the St. Louis Village Plan” (Loudoun County, January 8, 2024), https://www.loudoun.gov/DocumentCenter/View/188680/Draft-St-Louis-Village-Plan-01-08-24; Patrick Szabo, “St. Louis Residents Push to Block Subdivision,” LoudounNow.com, October 21, 2019, https://www.loudounnow.com/news/st-louis-residents-push-to-block-subdivision/article_90f87768-9a4e-5670-a4ab-2b8ae5defdaa.html; Pastor Charles Thompson, “How To Fight A Bully With Money,” Middleburg Eccentric, April 26, 2020, Vol. 16 Issue 12 edition.

[3] “June 9, 2021 Loudoun County Board of Supervisors Special Business Meeting,” June 9, 2021, https://loudoun.granicus.com/player/clip/6694?meta_id=195377; St. Louis Village Plan Task Force, “Draft of the St. Louis Village Plan” (Loudoun County, January 8, 2024), https://www.loudoun.gov/DocumentCenter/View/188680/Draft-St-Louis-Village-Plan-01-08-24: 14.

[4] “St. Louis Residents Concerned Development Would Endanger Water, Graves,” LoudounNow.com, September 13, 2019, https://www.loudounnow.com/archives/st-louis-residents-concerned-development-would-endanger-water-graves/article_56f0ebbb-b95b-5021-b115-7eb9f0419440.html; Cindy Sabato, “Standing with St. Louis...And Now Aldie,” The Piedmont Environmental Council (blog), December 14, 2020, https://www.pecva.org/resources/publications/piedmont-view/standing-with-st-louis-and-now-aldie/.

[5] “Conveyance and Interim Lease of Approximately 6.31 Acres of County Property to Aldie Community Development Company, LLC” (Loudoun County Board of Supervisors, January 13, 2021), https://loudoun.granicus.com/MetaViewer.php?view_id=77&clip_id=6520&meta_id=188011; Patrick Szabo, “County to Purchase St. Louis Property for $1.5M, Averting Development,” LoudounNow.com, October 12, 2020, https://www.loudounnow.com/news/county-to-purchase-st-louis-property-for-1-5m-averting-development/article_1c0800b3-eafb-5e8a-b19e-798b5c91ec71.html.

[6] St. Louis Village Plan Task Force, “Draft of the St. Louis Village Plan” (Loudoun County, January 8, 2024), https://www.loudoun.gov/DocumentCenter/View/188680/Draft-St-Louis-Village-Plan-01-08-24: 7.

[7] “St. Louis Village Plan | Loudoun County, VA - Official Website,” Loudoun County, https://www.loudoun.gov/5831/St-Louis-Village-Plan.

[8] “St. Louis Village Plan Task Force Boards & Commissions,” Loudoun County, https://onboard.loudoun.gov/board/4419.

[9] Nathaniel Cline, “Kuhns Seek to Purchase St. Louis Property, Stave off Proposed Development,” Loudoun Times-Mirror, November 16, 2021, https://www.loudountimes.com/news/kuhns-seek-to-purchase-st-louis-property-stave-off-proposed-development/article_f4c194ba-4706-11ec-a766-3f9bf5961b23.html.

[10] “Kuhns to Buy Saint Louis Property, Protect from Development,” LoudounNow.com, November 16, 2021, https://www.loudounnow.com/archives/kuhns-to-buy-saint-louis-property-protect-from-development/article_c1c69296-ad65-578c-a532-821602337ee0.html; Nathaniel Cline, “Loudoun County Supervisors Order Preservation Plan for St. Louis,” Loudoun Times-Mirror, January 26, 2022, https://www.loudountimes.com/news/loudoun-county-supervisors-order-preservation-plan-for-st-louis/article_6d12b51a-7d86-11ec-ae60-c390f8a22241.html.

[11] Antonio Olivo, “Loudoun County Farms Are Leaving. There’s a Fight over How to Save Them.,” The Washington Post (Online), August 20, 2023, sec. Local, https://www.proquest.com/docview/2853698378/citation/5A325235FACD4940PQ/1.

[12] “Discover the Story: About Us at JK Land Holdings, LLC,” JK Landholdings, https://www.jklandholdings.net/about-us/.

[13] “JK Land Holdings Creed: Community, Conservation, Development,” JK Landholdings, https://www.jklandholdings.net/jklh-creed/.

[14] Loudoun County Department of Planning and Zoning, “Conservation Easements in Loudoun County | Loudoun County, VA - Official Website,” https://www.loudoun.gov/2816/Conservation-Easements-in-Loudoun-County.

[15] Julio Ortiz, “850 Acres Placed into Easement by Old Dominion Land Conservancy for Land Owned by Kuhn Family,” JK Landholdings, June 15, 2022, https://www.jklandholdings.net/850-acres-placed-into-easement-by-old-dominion-land-conservancy-for-land-owned-by-kuhn-family/.

[16] Antonio Olivo, “Loudoun County Farms Are Leaving. There’s a Fight over How to Save Them.,” The Washington Post (Online), August 20, 2023, sec. Local, https://www.proquest.com/docview/2853698378/citation/5A325235FACD4940PQ/1.

[17] Sarah Vogelsong, “Va.’s Reliance on Tax Credits for Land Conservation Is ‘certainly Not Equitable,’ Review Finds • Virginia Mercury,” Virginia Mercury (blog), August 24, 2021, https://virginiamercury.com/2021/08/24/northam-admin-criticizes-state-land-conservation-policy-as-inequitable/.

[18] Levi Van Sant, “‘Into the Hands of Negroes’: Reproducing Plantation Geographies in the South Carolina Lowcountry,” Geoforum 77 (December 1, 2016): 196–205, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.10.019.