Tinner Hill: Culture of Displacement - Segregation and Lee Highway

In a continuation of targeted choices from three decades prior that gerrymandered Falls Church, specific laws and development targeted Black owned land, displacing the community in a slow process over the first decades of the new century. These choices would incrementally seek to pen them in, mark their land as worthy of removal, and ultimately ghettoize Black space. Thus, highlighting a clear the process of displacement in place, one eventually pushed over the edge into physical displacement. Though the segregation ordinance passed in 1915 was never officially enforced, it had a 30 year stay in the Laws of the Town of Falls Church and clearly defined zones of who should be where. In the case of Lee Highway, homes were forcibly moved, and land was taken through eminent domain – foreshadowing a time three to four decades ahead in the era of Urban Renewal. While some Black community members of Falls Church, including E.B. Henderson, saw the history of race relations between Black and white residents as one of relatively “pleasant relationship[s] and peaceful accord,”[1] the choice to push segregation, and the placement of Lee Highway make clear the view of the town towards its Black residents. These intentions reflect the processes of displacement in place, and encounters with slow violence that built up over time starting with the segregation ordinance and ending in physical displacement in 1922.

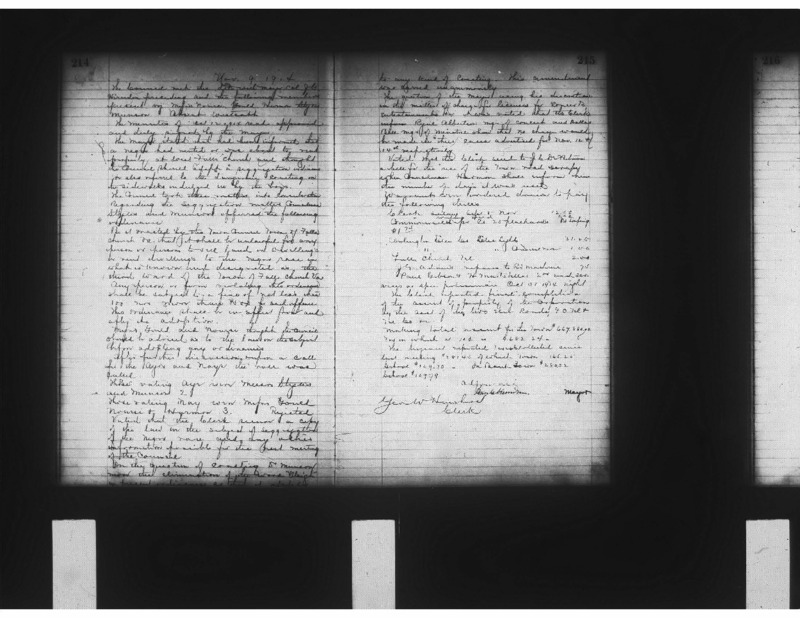

The 1915 segregation ordinance is central to the experience of Tinner Hill in the twentieth-century. Proposed on November 9th, 1914 in the Town Council of Falls Church, the original ordinance was proposed by Mayor John B. Herndon in response to the supposed rental of a property by a Black man in West Falls Church.[2] According to town meeting minutes, following unrecorded discussions, Councilmen Munson and Styles proposed the towns first segregation ordinance, reading:

“Be it enacted by the Town Council, Town of Falls Church Va. That it shall be unlawful for any person or persons to sell land or dwellings to the Negro race in what is known and designated as the Third Ward of the Town of Falls Church VA. Any person or firm violating this ordinance shall be subject to a fine of not less than $100 no more than $500 for each offence.”[3]

While this was rejected, 3 nay votes to 2 ayes, over the next two months, the town council shaped the ordinance finally settling on a law designating two districts, one white and one Black based upon that which held the majority of the respective races.[4] For the Black residents of Falls Church and Tinner Hill, this move came as a shock and a surprise; and in the case of E.B. Henderson, Tinner Hill resident and civil rights activist, they were only made aware of this over a month after its original proposal.[5]

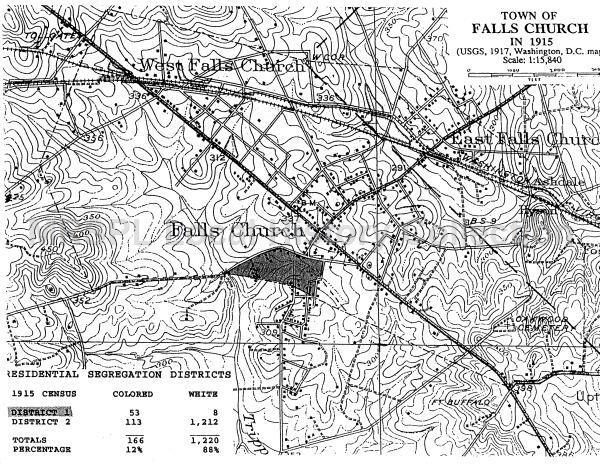

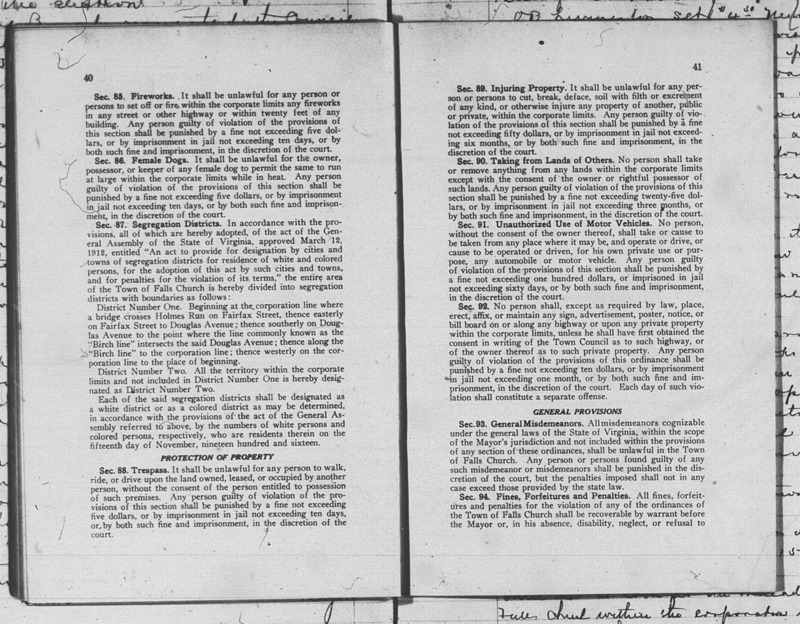

In May of 1915, the town voted on the ordinance in a Town Council meeting inviting all qualified voters to express approval or disapproval of the "segregation of the races within the town."[6] Following this, the Town Council met June 28, 1915 and established the system of two districts, with the Black district comprising 32% of the town population confined to 5% of the land.[7] While over the next two years the legality of the bill would be protested, challenged by Tinner Hill residents (explored in the following section), and fought in the state courts – its ultimate viability rest in the opinion of the Supreme Court case Buchanan v. Warley, which decided that segregation through zoning is unconstitutional in 1917.[8]

Yet, the law stayed on the books for the next three decades even after its constitutionality was decided, and only officially being repudiated by the City Council in 1999.[9] Looking at the map of the established districts, drawn in 1917, the limiting effect of the segregation law is clear. The Black community would have been penned into a small space comprised mainly of the Tinner Hill community and the remaining sections of the old Black communities gerrymandered out in 1887. While white residents would be able to live wherever, and buy from whomever they chose to, Black residents would be limited to only selling to white residents, and buying in District 1, designated for Black residents.[10]

By establishing these districts, Falls Church enabled displacement in place for the Tinner Hill community. Even though the law was held unconstitutional, it lingered, it marked the land, and it marked the Black community including the brave residents of Tinner Hill who organized to fight back against the law – creating displacement in place. The experience of Tinner Hill in the aftermath of the segregation ordinance reflects Andrea Roberts and Maia Butler’s central theme of displacement in place. They posit that displacement in place “does not involve physical movement, but takes the form of constraints on livelihoods, and cultural practices and, as a result displaces futures.” Through situating the community in District 1 as other, as displaceable – as “elsewhere” – and continuing a process of removal that began in 1887, the town moved “non-white experience and vision” to the margin, “outside of the normal in a way that erases everyday struggles and spatial productions (4) and racializes space toward related processes of expulsion, vulnerability, displacement, abandonment and discovery.”[11] By essentializing this space within Falls Church as Black through attempted segregation, Falls Church demarcated District 1 and therefore Tinner Hill as “elsewhere.”[12]

Through creating segregation districts, active or not, the Town of Falls Church mapped Black claims to space as vulnerable and marginal. E.B. Henderson rightfully held fears of what an active segregation law would do to Tinner Hill and the Black community of District 1 – ghettoization and unequal opportunity, development, and what Roberts and Adams would call constrained livelihoods.[13] However, its outcome still created what Katherine McKittrick would call the uninhabitable geography by marginalizing the district. This in turn creates a site of uninhabitability allowing for the myth of progress to creatively extract space, limit possibilities and mark those who are othered within the uninhabited as nobody.[14] With this, the logics of progress and expansion allowed for the extraction of Black space within Tinner Hill – made clear by the movement from displacement in place to physical displacement in 1922 with the building of Lee Highway through the heart of Tinner Hill.

Half a decade later, more turmoil and displacement came for Tinner Hill. The construction of the Lee Highway in 1922 brought with it early signs of growth, development, and suburbanization in Falls Church and Northern Virginia at large. Planned to stretch from coast to coast across the southern portion of the US, the highway was named after Confederate General Robert E. Lee in a show of opposition to highway being built through a northern section of the US bearing the name of Abraham Lincoln.[15] Its final plan took it directly through the heart of a Black community, Tinner Hill. The highway would end up splitting Tinners Hill Road (upon which all of the original Tinner Family plots of land lay), Henderson Family plots, and other residents of the community surrounding Tinner Hill. The acquisition of the land necessary for this road required eminent domain.[16] Following its completion the road was also widened to three lanes, requiring further construction, more property acquisition and tree removal causing further issue in the community.[17]

Charting a path from 1887 to 1922, the marginalizing of geography made possible the eventual forced movement of Black homes and the acquisition of Black land. Displacement in place in the aftermath of retrocession and a failed segregation attempt marked the land and paved the way for physical displacement in Tinner Hill. Cutting directly through what amounted to District 1 of the 1915 segregation ordinance, the goal of the road was to bring with it an economic boom, better roads, and a brighter future for the burgeoning suburban landscape of Northern Virginia.[18] The creation of Lee Highway acted as a tool of slow violence by way of displacement in place through racist iconography splitting a community, taking land through eminent domain, and forcing some to physically move their homes - including the Henderson Family who had to move their home 150 feet to the north as the road would have cut through his house.[19] At a deeper level the acquisition of territory, and the drive for improving land also crafted the narratives that spawn the myth of progress.

These narratives can be seen in the way it was discussed by the broader community of Falls Church, and Northern Virginia. Nan Netherton, in Falls Church A Village Revisited highlights the way in which a local real estate agent reported “‘one thousand per cent increase in sales and one hundred per cent increase in value’ of property along the new highway.”[20] However, as Anna Buczkowska et al. point out, it is “unlikely that the location was chosen so that the black landowners would profit from new development along the roadway, and at present there is no evidence of the original landowners being the recipients of the boom in property values.”[21] Thus, while the broader white community of the surrounding region were experiencing economic booms as suburbanization first began, Tinner Hill was divided again.

While there were no clear intentions spelled out to harm the Black community displaced in place, the painful irony of naming a road after someone such as Lee is clear. Even more so when it is built upon the uneven racial geographies of a community all but sequestered to a small region of Falls Church, now bisected by a road the purpose of economic gains and development for those outside of the community. This rhetoric of progress – of 1000% increases in sales, new roads spawning a new era for the rural countryside – at the expense of a Black community highlights the way in which slow violence and the narrative of progress are interlinked.

The myth of progress is born out of this period and played out over the coming decades. The work to prime the land for the neo-colonial expansion of the Post-War era is due in part to acts of retrocession in the late-nineteenth-century, the planned but thwarted segregation of 1915, and a pre-Urban Renewal era tactic of disrupting a Black enclave by building a highway through it. Slow, accretive acts that mount up attrition over the decades establish the process of forgetting, a process of creative extraction, through slow change and isolation of Black communities. However, this does not mean the community sat by and let these events occur without fighting for their place. Instead, Tinner Hill and its surrounding community took to organizing in the early twentieth-century and built upon a strong preexisting community network to establish the first rural branch of the NAACP and have maintained their community for generations.

[1] Edwin Bancroft (E.B.) Henderson, “Letter from E.B. Henderson to Councilman, Dr. J. B. Gould,” January 4, 1915, Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library.

[2] “Town Council of Falls Church Minute Book” (Vol.1. 1875-1921), Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library: November 9, 1914, page 214.

[3] Ibid.

[4] “Town Council of Falls Church Minute Book” (Vol.1. 1875-1921), Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library: January 11, 1915, page 219-220.

[5] Edwin Bancroft (E.B.) Henderson, “Letter from E.B. Henderson to Councilman, Dr. J. B. Gould,” January 4, 1915, Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library; Edwin Bancroft (E.B.) Henderson, “Letter from E.B. Henderson to W.E.B. Du Bois,” January 20, 1915, Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library.

[6] “Town Election! (1915 Referendum Vote),” 1915, 100 Years Black Falls Church, Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation, http://100yearsblackfallschurch.org/items/show/32.

[7] Anna Buczkowska, Basem Saah, and Professor Paul Kelsch, “Tinner Hill, Virginia: A Witness to Civil Rights” (Blacksburg, VA, Landscape Architecture Program, Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University, 2011): 20.

[8] Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917).

[9] “Civil Rights History & Tinner Hill,” Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation, February 15, 2018, https://www.tinnerhill.org/educational-resources/2018/2/15/civil-rights-history-tinner-hill.

[10] “Town Council of Falls Church Minute Book” (Vol.1. 1875-1921), Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library: June 28, 1915, page 231-232.

[11] Anna Livia Brand “Say Its Name – Planning Is the White Spatial Imaginary, or Reading McKittrick and Woods as Planning Text” Planning Theory & Practice 19, no. 2 (March 15, 2018): 269 (in Lisa K. Bates et al., “Race and Spatial Imaginary,” Planning Theory & Practice 19, no. 2 (March 15, 2018): 254–88.)

[12] Katherine McKittrick and Clyde Adrian Woods, Black Geographies and the Politics of Place (Cambridge, Mass: South End Press, 2007): 4.

[13] Edwin Bancroft (E.B.) Henderson, “Letter from E.B. Henderson to Councilman, Dr. J. B. Gould,” January 4, 1915, Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library; Edwin Bancroft (E.B.) Henderson and The Colored Citizens’ Committee, “Letter Written to the Falls Church Town Council on Behalf of the Colored Citizens Protesting the Establishment of ‘Segregation Districts.,’” January 8, 1915, Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library.

[14] Katherine McKittrick, “Plantation Futures: Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism,” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 17, no. 3 (November 2013): 7-8.

[15] Anna Buczkowska, Basem Saah, and Professor Paul Kelsch, “Tinner Hill, Virginia: A Witness to Civil Rights” (Blacksburg, VA, Landscape Architecture Program, Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University, 2011): 22; Nan Netherton and Bradley E Gernand, Falls Church: A Virginia Village Revisited (Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Company, 2000): 103.

[16] Nan Netherton and Bradley E Gernand, Falls Church: A Virginia Village Revisited (Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Company, 2000): 103-104.

[17] City of Falls Church Department of Development Service, “South Washington Street Corridor Planning Opportunity Area 2 ‘2. Background’” (City of Falls Church, 2013), https://www.fallschurchva.gov/468/South-Washington-Street-Small-Area-Plan.

[18] Nan Netherton and Bradley E Gernand, Falls Church: A Virginia Village Revisited (Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Company, 2000): 103-104.

[19] Edwin Bancroft Henderson II, “Falls Church’s Black History: A Welcoming Community That Has Not Always Been So Welcoming | Falls Church Pulse,” Falls Church Pulse, February 15, 2024, sec. Analyses, https://fallschurchpulse.org/falls-churchs-black-history-henderson/; Edwin Bancroft (E.B.) Henderson, Transcript of a Tape Recorded Interview With Dr. E. B. Henderson By WMAL, 1962, Northern Virginia oral history project collection (C0030), George Mason University Libraries Special Collections Research Center: part 3, pg 7.

[20] Nan Netherton and Bradley E Gernand, Falls Church: A Virginia Village Revisited (Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Company, 2000): 103; William Page Johnson, II, “My Grandfather’s Lee Highway” (The Fare Facts Gazette, Winter 2008), https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/transportation/sites/transportation/files/Assets/Documents/PDF/Confederate/Document%20-%20History%20of%20Lee%20Highway%20for%20a%20Historic%20Fairfax%20City%2C%20Inc.%20Newsletter.pdf.

[21] Anna Buczkowska, Basem Saah, and Professor Paul Kelsch, “Tinner Hill, Virginia: A Witness to Civil Rights” (Blacksburg, VA, Landscape Architecture Program, Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University, 2011): 24.