Home

Welcome...

Welcome to the Northern Virginia Archive of Black Community Resistance, an online capstone graduate research project produced by Jacob Connelly, a Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies student at George Mason University. Centering the encounters of three Black communities with slow violence, suburbanization, and the expansion of Northern Virginia, this project hopes to highlight the work of Tinner Hill, Gum Springs, the village of St. Louis and other communities who have fought and continue to fight for access to homes, land, and the maintenance of their communities.

Introduction:

Housing has long been a site of exclusion for minoritized communities throughout the United States. The effects of this can be seen in segregation, red lining, zoning, and in a more modern context – gentrification. The historic practices of exclusion, removal, and barriers to access both in urban and suburban locations is commonly discussed by historians. Scholars often explore and analyze acts of exclusion and removal such as segregation, redlining, restrictive covenants, or practices of urban renewal that fuel systems of racial capitalism and inequity when discussing suburban expansion.[1] However, less attention is paid to the significant effects barriers to access, displacement, and structural restrictions have had on small, primarily rural Southern Black communities that predate the periods of post-World War II development formally called suburbanization. Northern Virginia provides many opportunities to study suburbanization, housing, and the experiences of small Black primarily rural communities.

Encompassing Fairfax County, Loudoun County, Prince William County, Arlington County and Alexandria County, the region of Northern Virginia contains some of the nation’s wealthiest counties and lies at the doorstep of the nation’s capital. Ranging from the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains in northeast Loudoun, to the Potomac River on the borders of Fairfax, Arlington, and Alexandria the region is geographically diverse, with natural forests and rivers competing with historic parks, plantations, cities, and modern suburban development for space. Trading the farm field or expansive former plantation for the bedroom community during the mid-twentieth century, Northern Virginia now acts as an extension of the nation’s Capital and State Department apparatus.

In its current iteration, Northern Virginia’s landscape is dotted by suburban bedroom communities and populated by affluent, upper middle-class families. It is where DC sleeps. The area sees itself as progressive with racial and cultural diversity, a clear and intentional statement of difference to separate itself from the history and image of the rest of the state. This progressive self-image is constructed using a curated narrative of growth and development demonstrating an overcoming of the area’s Jim Crow and Antebellum past, while attempting to preserve connections to a rich history predating suburbanization. Throughout the twentieth- and continuing into the twenty-first-century, the suburbanization, expansion, and largescale development of Northern Virginia’s economy, suburbs, and planned and existing communities has led to a massive increase in population, significant demographic shifts, and a great influx in wealth. Yet the geographies of Northern Virginia still reflect the history of Virginia as a slave society, and its long history of segregation following emancipation. The attempts to create and foster a progress-based, economic nucleus in Northern Virginia relied upon taming and neo-colonial acquisition of rural landscapes mythologized as empty. The work to create modern Northern Virginia heavily relied upon the displacement of long-established Black communities that dotted the landscape – a process that continues to this day.

This culture of progress that surrounds Northern Virginia’s lifestyle and development has been shaped through the twentieth- and twenty-first-century and is pervasive in the way the region views itself. This view forms what this project calls the “myth of progress.” The myth of progress is a constructed forgetfulness that surrounds and shapes the ways in which Northern Virginia grew to become what it was and how Northern Virginians view that progress of suburbanization and growth. [2] This myth sustains a constructed image of Northern Virginia as a region that is always growing, developing, and improving for the betterment of all, built off the backs of great men and women shaping a rural landscape viewed as empty into an economic nucleus. This myth holds a perception that expansion and development is good even if it undermines, displaces, or damages existing communities. Thus, while the narratives that surround the development of Northern Virginia center progress for the betterment of all, progress was not always for the betterment of all.

Growth and development, as with many locations, often occurred at the expense of others, particularly Black towns, neighborhoods, and enclaves with long histories.[3] This is exemplified by the experiences of Willard, VA, a Black community displaced and dismantled for the construction of Dulles International Airport. Through multifaceted means that often appear harmless, or meant for the betterment of the general community, expansion, development, and poor city planning takes the form of slow violence that endangers communities and leaves them vulnerable to displacement. Yet these Black communities did not give up in the face of adversity or displacement. They worked to organize their community against removal and sustain their claims to space and place.

The three Black communities this project focuses on are Tinner Hill, in Fairfax County, Gum Springs, in Fairfax County, and the village of St. Louis in Loudoun County. Each of these communities faced decades of slow violence and direct attacks on their community’s claims to space and place. Slow violence is the concept presented by Rob Nixon, it focuses upon the slow accretive actions that displace and restrict communities from access to land, and opportunity.[4] Tactics of slow violence were and still are utilized as Northern Virginia expands and develops further. These actions have marked (or are still marking) many Black towns, neighborhoods, and enclaves in Northern Virginia as invisible, unviable, unworthy of existing – rendering them vulnerable to displacement, or prone to being “forgotten.” Thus, for those who do not inhabit these communities there lacks an acknowledgement that they even exist. Forgetting Black claims to land is a violent – slow violent – act. “Black claims to and sense of place are subjugated” according to Andrea Roberts and Maia Butler, and therefore “deemed illegible, and omitted from urban planning, historic preservation, and public history.”[5] Yet, these communities never quit in the face of what could appear insurmountable efforts to make Black geographies illegible.

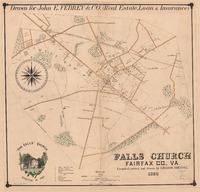

Each of the three communities focused on in this project provide different opportunities to pinpoint moments and experiences of Northern Virginia’s Black communities in their interactions with slow violence and displacement throughout the twentieth- and into the twenty-first-century. The first community is Tinner Hill. Located in south central Falls Church, Tinner Hill exists upon the 2.5-acre tract of land purchased by Charles Tinner in 1890.[6] Tinner Hill highlights an important experience for Black community members of Fairfax County as they experienced both slow violence and displacement in place, and clear aggression from the white community that sought to remove them. [7] Their encounters with laws that sought to segregate Falls Church, expansion through housing development, road development, the commercialization of Falls Church, and other tactics of displacement in place represented opportunities for the community to fight back. Tinner Hill’s resistance is made most clear in their creation of the Colored Citizens Protective League – one of the first rural NAACP branches in the country, and the Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation which maintains the memory and place of the community.

The second community is Gum Springs. Lying just north of Mt. Vernon, VA, upon land formerly owned by George Washington, Gum Springs was established by West Ford in 1857 when he split his 214-acre tract of land purchased in 1833 for his descendants.[8] Throughout the decades the community has always culturally thrived, with many of Ford’s descendants remaining there today. However, financially Gum Springs began to struggle in the mid-twentieth-century. Their encounters with a state and local government that failed to provide proper funding or acknowledge their needs for decades left their primarily rural community to struggle with poor water drainage, and suffering infrastructure, and unemployment. This was compounded by hostile ordinances used to mark places like Gum Springs as filthy and crime ridden – worthy of removal in a time when Northern Virginia and the surrounding Fairfax and Alexandria Counties were seeing massive suburban growth and investment.[9] Yet the community banded together to fight against potential evictions from hygiene laws, and poor city planning through legal and community-driven measures instigating change and fighting for funding. Community organizing from the Saunders B. Moon Community Action Association, and subsequent organizations have continued to fight against slow violence that seeks to displace their community to this day.

The final community is the Village of St. Louis (St. Louis). Situated outside of Middleburg, VA in western Loudoun County, St. Louis is a small community but the largest of the Black villages in the County. Named by Phil McQuay – store owner and prominent early resident of the community – for the city in Missouri in the late 1800s, St. Louis was settled as early as 1877 with its first Baptist Church by families and descendants of those who were formerly enslaved.[10] However, St. Louis’s experience with development and expansion is much more recent than Tinner Hill or Gum Springs, whose histories go back just as far. St. Louis is still the most rural of the three communities, however expanding urban and suburban sprawl from the eastern third of Loudoun County and failing measures to control development in the western two-thirds of the County mean suburbanization and change has begun to encroach upon small communities like St. Louis..[11] As more affluent communities move into the region, descendants of St. Louis’ earliest residents have felt the pressures of expansion, rising land prices, and generations of infrastructural neglect. The fight to stave off predatory development in their village has put St. Louis in a fluid situation of trying to conserve their land. This conservation effort, led by a local entrepreneur and self-described conservationist, leaves open questions of what land conservation means for the village and Loudoun County, how to maintain St. Louis’s historic community, and how to service a long-underserved community without gentrifying. St. Louis’ experiences demonstrate modern forms of slow violence in a primarily rural Southern Black community, what the myth of progress looks like in Loudoun County, and the ongoing challenges to conserve Black history in a burgeoning frontier.

The emotional and geographical struggles of Tinner Hill, Gum Springs, and St. Louis to persist must continue to be acknowledged. Slow violence and displacement in Northern Virginia’s development through the twentieth- and twenty-first-century has enabled this process of forgetting and undermined the work of many Black communities who fought and continue to fight back against encroachment, forms of displacement, and the expanding suburban landscape which has erased and homogenized so many communities. Keeping the stories of resistance, community organizing, and emotional/physical claims to space visible helps to keep geographies alive and mapped, even if the community may not be anymore.

Problem:

While the research on segregation, racism in housing, and displacement is broad, research on the specific Black geographies of Tinner Hill, Gum Springs, and St. Louis, as well as the broader Northern Virginia region is not as deep. There is a need to understand long-term systems of removal and exclusion through actions of slow displacement couched in terms of progress, environmental racism, underfunding and gentrification, and their connections to Black geographies both in Northern Virginia and in the whole of the United Sates. The broader process of suburban development throughout Northern Virginia during the twentieth-century had significant effects on Black communities.

In the monumental endeavor to grow and develop Northern Virginia throughout the twentieth-century, residents, developers, and stakeholders have often repeated the narrative about the region's progress. It holds that Northern Virginia is something of a progress-based development driven economic nucleus. That it was built upon land characterized as underutilized farm space and undeveloped that was waiting to be operationalized for greater goals and gains – where progress is always happening and always necessary.[12] The costs of that progress are rarely questioned and when it is it is in relation to its effects on predominately white communities and movement away from traditional lifestyles to more modern ones.[13] Driven by systems of racial capitalism – a concept coined by Cedric Robinson – that place emphasis on white spaces, presumptions of non-white spaces as lesser-than have been established, therefore these spaces become “empty” and acquirable. [14] Because of this, Black communities of Northern Virginia have faced decades of slow violence by acts of encroachment, disinvestment, lack of acknowledgement of their needs and wants, pricing out often ending in their removal or displacement– yet rarely is it discussed. This equates to a two-fold process of slow violence that builds on displacement in place, often overflowing into physical displacement.

Slow violence is “a violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.”[15] Rob Nixon’s concept of slow violence, from their book Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, is used here to encompass slow acts of violence through goals and actions of development, and expansion that surround these Black communities and enclaves. It is experienced through displacement in place – a concept briefly mentioned in Nixon’s work, but further outlined by other scholars of Black geography such as Andrea Roberts and Maia Butler, as well as scholars of displacement. This experience of displacement in place is shaped by layers of compounding uneven development that create disproportionate outcomes, leaving geographies vulnerable targets for extraction, and physical displacement.[16] Displacement in place here draws upon the ideas of Nixon’s slow violence while employing Black geographic frameworks of Andrea Roberts and Maia Butler’s emotional and physical interactions with displacement in Southern Black geographies.

Displacement in place is part of the process of slow violence occurring through constrained livelihoods under compounding layers of uneven development, barriers to access for structures and funds in communities, and land use decisions that may not be equal or may not help.[17] By failing to accurately address community needs, or even acknowledge their needs, “Black claims to and sense of place are subjugated, deemed illegible, and omitted from urban planning, historic preservation, and public history.”[18] Black claims to space and place are forgotten, subjugated, and made illegible – therefore, physical displacement is made possible by displacement in place. It is not always achieved, but it is the final act of slow violence’s attrition upon communities.

The narratives of progress that color tales of creating the modern Northern Virginia, and frame the goals of its expansion through racial capitalist visualizations, which create a colonial attitude towards the establishment of suburban frontier, where the land is fallow and vacant waiting to be harnessed,[19] and if you build it “they will come.”[20] The story told of Northern Virginia told by many prominent residents, local historians, and developers lauds the primarily white, wealthy developers and local leaders of the twentieth- and twenty-first-century for their progress-based attitude of building up this land for the good of everyone. This narrative that surrounds Northern Virginia acts as an extension of slow violence creating what I call “The Myth of Progress.”

“The Myth of Progress” undergirds a significant portion of Northern Virginia’s suburbanization and expansion. Born out of the prevailing narrative of Northern Virginia, and its history of constant development for the good of its people, this “myth of progress” is hinged upon western orders of expansion and development as both necessary and good. The myth also assumes that empty land is the antithesis to progress and therefore land must be settled, developed, or occupied. Land perceived as empty through constructed forgetfulness, and dominant spatial orders predicated on whiteness reifies the perception that expansion and development is good even if it undermines, displaces, or damages existing communities. This process of undermining, damaging, or displacing communities plays into the process of forgetting put forward by slow violence, and displacement in place.

The myth of progress paints the idea of Black space as unimaginable. Working in tandem with slow violence and displacement in place – the myth of progress’s structure of constructed forgetfulness denies Black claims to space and place. By perceiving space as both empty and needing to be developed, therefore impossible to be claimed by those outside of western logics of racial hierarchies, Black spaces that dotted Northern Virginia were and still are made illegible to the white, wealthy, and powerful stakeholders who control the means of producing and funding suburban structures. Therefore, these spaces are able to be funded less, encroached upon, and both unrecognizable and paradoxically removable in the process of progress. This conceptual framework is further laid out on the web page “Literature and Frameworks,” as the framework is essential to this project.

Goals of this Project:

This project seeks to address certain issues in the historiography of Northern Virginia’s development – specifically a lack of critical analysis of suburbanization and development, and the impacts that it had on Black communities, as well as their response to such effects. To do this, this project examines the suburbanization and development of Northern Virginia during the twentieth-century and into the twenty-first-century by focusing on Tinner Hill, Gum Springs, and St. Louis, all Black towns, villages, or enclaves in Northern Virginia. Analyzing the history of racism in suburbanization, the long-term development of Northern Virginia, and its ties to slow forms of displacement is essential to understanding the effect it had and still has on Black communities and Black geographies in the area. To acknowledge the existence of Black geographies in Northern Virginia and their fight against development and displacement is a step forward in understanding tactics of slow violence that sit under the surface of the progress-based narrative of Northern Virginia’s development.

Due to the nature of the narrative of progress in Northern Virginia, many of the stories from those Black Northern Virginians who experienced the effects of slow violence and long-term displacement have been left underexamined, if ever recognized. Assumptions that land was sparsely inhabited means many communities are forgotten from records or mentioned in passing. When they are acknowledged, these communities are rarely given opportunities to share their history in official records, and their actions of resistance are given a lack of recognition.[21] This project seeks to address the general lack of written histories that acknowledge the existence of displaced and resisting Black geographies in Northern Virginia, by telling a history of their fight against the state-level and local actors who sought to attack their communities through direct or indirect means.

To address the need for a deeper inspection of Northern Virginia’s suburbanization and challenge the prevailing narrative of its development (the myth of progress), this project has created an archive of Black community resistance. The purpose of this archive is to establish a history of Tinner Hill, Gum Springs, and St. Louis throughout the extended period of suburbanization and massive development in Northern Virginia, while building out the story of these three community’s resistances against forms of displacement – both in place and out of place. By pinpointing key moments of direct and indirect attacks on their communities, and the resistance taken against it this project sought to answer the following sets of questions:

- How does the myth of progress belie actions of slow violence?

- What does displacement in place look like in these Northern Virginia communities?

- How do strategies of displacement in place utilized in Northern Virginia facilitate forms of physical displacement?

- What strategies were used by members of the Tinner Hill, Gum Springs, and St. Louis communities to resist multifaceted forms of displacement?

- How have community structures evolved in Tinner Hill, Gum Springs, and St. Louis, are they able to meet future needs for community maintenance?

The goal of this project is to create a digital history resource that houses both a detailed history and archive of slow violence and community resistance against displacement in three of Northern Virginia’s many Black communities. These components will lay out the history and implications of Tinner Hill, Gum Springs, and St. Louis’ interactions with, and opposition to slow violence by way of suburban encroachment, and broader acts of displacement throughout the twentieth-century and into the twenty-first-century. This archive aims to be a space where Black community resistance is showcased and celebrated. It will serve as a space for communities to interact with, to inspire resistance, provide models of how to create a community effort against a hostile state or local government, and ways to withstand displacement tactics. Explore this archive further to examine Tinner Hill, Gum Springs, and St. Louis’s work to challenge expansion, displacement, and erasure during the twentieth- and twenty-first-century.

Methods:

This digital history resource seeks to bolster the research on Northern Virginia, historically Black communities, and their claims to space and place, and their encounters with slow violence in the form of suburbanization and development from the twentieth-century and into the twenty-first-century. This project has taken the form of a website containing “Mapping Histories”, as well as an archive of primary and secondary source documents to demonstrate Tinner Hill, Gum Springs, and St. Louis’ stories of interactions with and resistance against the expanding suburban frontier. Each location is given its own section that documents stories and experiences over the twentieth-century and into the twenty-first-century – mapping their histories in relation to development and suburbanization in Northern Virginia. As part of this project, an archive of primary and secondary source documents has been included to document each community, their experiences, and their work to organize against displacement – titled the Northern Virginia Archive of Black Community Resistance. The framework of the “Myth of Progress” informs what is included within the archive, the way the interactive components are presented, and how the research is conducted.

The structure of this project is in three parts, one for each community. With each section – split out by separate webpages for each community – including story maps, documents, and timelines of significant events in, and actions by these communities that trace their history, while providing written insights into their experiences with slow violence, expansion, and development.

The first community examined is Tinner Hill. Tinner Hill and Black Falls Church’s encounters with expansion and segregation demonstrates early actions of slow violence and direct attacks on Black spaces in Northern Virginia. The work of the CCPL/early Fairfax NAACP, and the community around Tinner Hill provides ample opportunities to study in the areas of resistance and potential displacement, and the existence of Black spaces in and between massive suburban and commercial growth.

The second community examined is Gum Springs. Gum Springs’ community organizing practices, and battles for better community infrastructure in the mid-twentieth-century requires deeper inquiries. Their persistence in fighting displacement, and their drive to continually maintain and improve the community provides decades of resistance work and organization, while demonstrating the multifaceted methods of displacement and slow violence that occurs over decades. Their continued survival illuminates the strength of Black claims to space and place in Northern Virginia.

The third and final community examined is St. Louis. Like many other small Black communities in the Piedmont regions of Northern Virginia, their encounters with expansion, suburbanization and displacement have come in more recent decades. St. Louis’ situation is one that is evolving, as land acquisition, development, and conservation efforts continue to shape the landscape. Their experience provides a possibility for more modern analyses of slow violence and its effects on Black communities, particularly in Northern Virginia as suburbia expands further into the Piedmont. The chosen method of research, telling the long history of suburbanization and development through the lens of slow violence, allows for a comparative analysis of these three communities. Using this type of analysis provides insight into their shared confrontations, and differing responses, on top of potential successes they experienced in their resistance.

[1] Lisa Bates, “Gentrification and Displacement Study: Implementing an Equitable Inclusive Development Strategy in the Context of Gentrification,” Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Publications and Presentations, May 1, 2013; Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, First edition. (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2017); Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York, UNITED STATES: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 1987).

[2] Russ Banham, The Fight for Fairfax: A Struggle for a Great American County, 2nd ed. (Fairfax, Virginia: GMU Press, 2020); Andrew Friedman, Covert Capital: Landscapes of Denial and the Making of U.S. Empire in the Suburbs of Northern Virginia, American Crossroads 37 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013); Eugene M. Scheel, The History of Middleburg and Vicinity: Honouring the 200th Anniversary of the Town 1787 – 1987 (Warrenton: Piedmont Press, 1987): p.196.

[3] Nancy Perry, Spencer Crew, and Nigel M. Waters, “‘We Didn’t Have Any Other Place to Live’: Residential Patterns in Segregated Arlington County, Virginia,” Southeastern Geographer 53, no. 4 (2013): 416.

[4] Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, 1st ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011): 2.

[5] Andrea Roberts and Maia Butler, “Contending with the Palimpsest: Reading the Land through Black Women’s Emotional Geographies,” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 112, no. 3 (2022): 829; Steven Woolf, “Deeply Rooted: History’s Lessons for Equity in Northern Virginia,” ed. Mary Lee Clark, The Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Center on Society and Health and the Northern Virginia Health Foundation., December 2021: 10.

[6]Historic American Landscapes Survey, creator, “Tinner Hill, Intersection of Tinner Hill Road and Washington Street/Lee Highway, Falls Church, Falls Church, VA” (National Park Service, July 29, 2011), Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/va2212/; Tinner Family Collection, “Charles Tinner Deed,” 100 Years Black Falls Church, http://100yearsblackfallschurch.org/items/show/159.

[7] Edwin Bancroft (E.B.) Henderson, “History of the Fairfax County Branch of the NAACP” (NAACP Fairfax County Branch, 1965): 1-4.

[8] Judith Saunders Burton, “A History of Gum Springs, Virginia: A Report of a Case of Leadership in a Black Enclave” (Doctoral Dissertation, Nashville, TN, George Peabody College for Teachers of Vanderbilt University, 1986), City of Fairfax Regional Library (Virginia Room): 25-27

[9] John Terry Chase, Gum Springs: The Triumph of a Black Community (Fairfax, Virginia: Heritage Resources Program of the Fairfax County Office of Comprehensive Planning, 1990).

[10] The Black History Committee of the Friends of the Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, Virginia, Loudoun County’s African American Communities: A Tour Map and Guide (Leesburg, VA: Black History Committee, Friends of the Thomas Blach Library, Inc., 2004): 20-21; Eugene M. Scheel, Loudoun Discovered: Communities, Corners & Crossroads, vol. Volume 3-The Hunt Country and Middleburg, 5 vols. (Leesburg, VA: Friends of the Thomas Balch Library, 2002): 85-86.

[11] Eugene M. Scheel, The History of Middleburg and Vicinity: Honoring the 200th Anniversary of the Town 1787-1987. (Middleburg, VA: Middleburg Bicentennial Committee, 1987): 161.

[12] Russ Banham, The Fight for Fairfax: A Struggle for a Great American County, 2nd ed. (Fairfax, Virginia: GMU Press, 2020); Steven Woolf, “Deeply Rooted: History’s Lessons for Equity in Northern Virginia,” ed. Mary Lee Clark, The Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Center on Society and Health and the Northern Virginia Health Foundation., December 2021: 14.

[13] Charles P. Poland Jr., From Frontier to Suburbia (Marceline, Mo: Walsworth Publishing Co., 1976): 394-396; [13] Eugene M. Scheel, The History of Middleburg and Vicinity: Honoring the 200th Anniversary of the Town 1787-1987. (Middleburg, VA: Middleburg Bicentennial Committee, 1987): 196.

[14] Brenna Bhandar, Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership, Global and Insurgent Legalities (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018): 102; Michael T. Kelly, “Land Speculation and Suburban Covenants: Racial Capitalism and the Pre-Redlining Roots of Housing Segregation in Syracuse, New York,” Antipode 54, no. 5 (2022): 1630-1631; Danielle M Purifoy and Louise Seamster, “Creative Extraction: Black Towns in White Space,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 39, no. 1 (February 1, 2021); Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (Chapel Hill, UNITED STATES: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

[15] Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, 1st ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011): 2.

[16] Rachel Pain, “Chronic Urban Trauma: The Slow Violence of Housing Dispossession,” Urban Studies 56, no. 2 (2019): 387; Danielle M Purifoy and Louise Seamster, “Creative Extraction: Black Towns in White Space,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 39, no. 1 (February 1, 2021): 47–66; Andrea Roberts and Maia Butler, “Contending with the Palimpsest: Reading the Land through Black Women’s Emotional Geographies,” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 112, no. 3 (2022): 828–37.

[17] Elizabeth L. Sweet and Elsie L. Harper-Anderson, “Race, Space, and Trauma,” Journal of the American Planning Association 89, no. 4 (October 2, 2023): 555.

[18] Andrea Roberts and Maia Butler, “Contending with the Palimpsest: Reading the Land through Black Women’s Emotional Geographies,” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 112, no. 3 (2022): 829.

[19] Lorenzo Veracini, “Suburbia, Settler Colonialism and the World Turned Inside Out,” Housing, Theory & Society 29, no. 4 (December 2012): 342.

[20] Russ Banham, The Fight for Fairfax: A Struggle for a Great American County, 2nd ed. (Fairfax, Virginia: GMU Press, 2020): xi.

[21] Falls Church Historical News and Notes (Falls Church, VA: Village Preservation and Improvement Society, 1993); Bradley E Gernand and Nan Netherton, Falls Church: A Virginia Village Revisited - George Mason University Libraries (Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Company, 2000); Charles P. Poland Jr., From Frontier to Suburbia (Marceline, Mo: Walsworth Publishing Co., 1976).