Tinner Hill: 100 Years of Community Resistance

While attempts to destabilize Black communities in Falls Church may have been successful as far as cutting their voting power following the 1887 retrocession, attempts to further destabilize the community were met with significant organization. At the tip of the spear was Tinner Hill’s efforts to smother efforts by the Town Council to segregate the town in 1915. The work of Tinner Hill, and Black Falls Church in the period paved the way forward for many Black communities in Northern Virginia as they sought to maintain their claims to space and place, while fighting for justice and equality in other facets including education and voting. This work created a lineage of community organizations that have worked to maintain Black spaces in Falls Church, and Tinner Hill’s efforts again lay at the forefront of this work. The efforts of the Tinner Hill and Black Falls Church community members to build strong organizations meant that in the twentieth-century, even as the community felt the wake slow violence and displacement, their structures evolved to face the challenges in front of them. This section examines the efforts of the Tinner Hill community to establish resistance fronts against displacement, how their efforts evolved, and what their efforts mean for the future of Tinner Hill.

As noted in the prior sections, “Exclusion, Slow Violence, foundations of the Suburban Frontier” and “Culture of Displacement - Segregation and Lee Highway,” the experience of Tinner Hill in the late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century was one of growing displacement in place. Exclusionary efforts by the Town of Falls Church gerrymandered the community opening the door for slow violence in its wake. The 1915 segregation ordinance first considered by Mayor John B. Herndon in November 1914, and eventually decreed by the Town Council in subsequent meetings looked to establish segregation districts in Falls Church. For some in the Black Falls Church community, it came as a shock to see such an ordinance be proposed. Yet, even in the face of this shocking move to enclose the Black community into around 5% of the town,[1] the Black community quickly acted to oppose this ordinance.

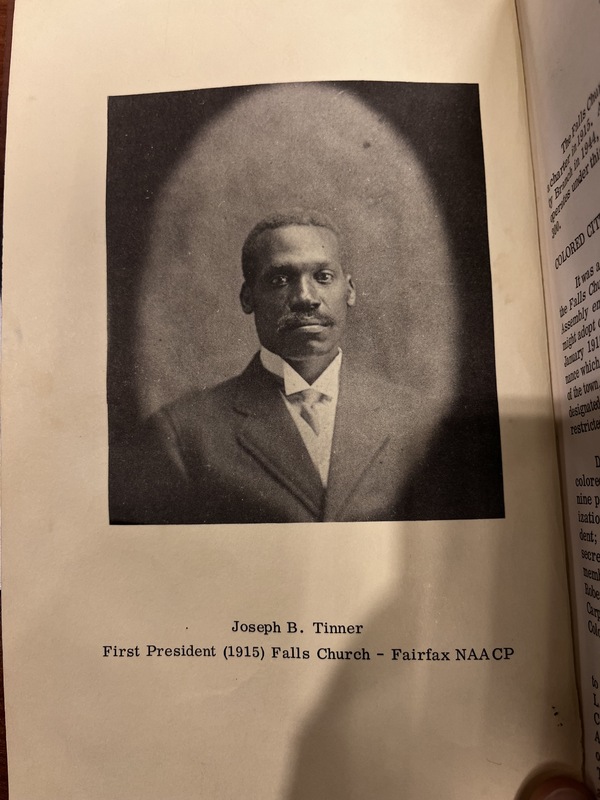

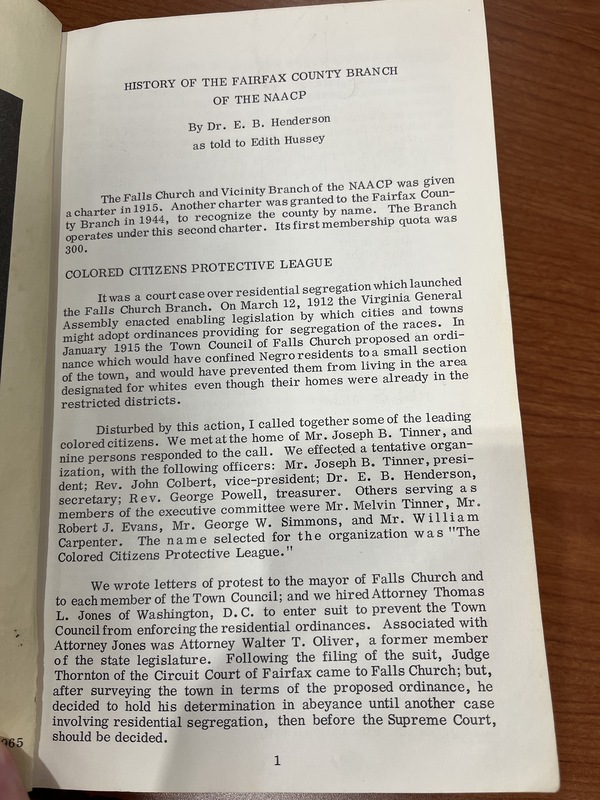

Organized in early January 1915, the Colored Citizens Protective League (CCPL) was started with the sole goal of protecting the Black community from segregation and further displacement in Falls Church. Going by many names in its early days – Colored Citizens Executive Committee, the Committee of Nine (sometimes Committee of the Nine), and Colored Citizens Committee – the CCPL’s work of organizing the Black community of Falls Church, driven by Tinner Hill, is commendable and formidable. The work of the Tinner Hill community was integral to this opposition. Joseph Tinner, son of Charles who originally bought the land in the century prior, and E.B. Henderson organized a front that would frustrate any efforts by the white community to segregate the town.

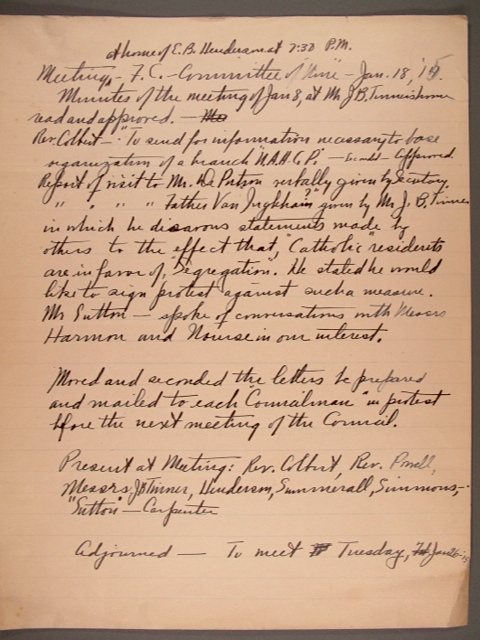

Upon E.B. Henderson’s discovery in a newspaper he cites as the “Commonwealth”, Henderson wrote to ask councilman Dr. J.B. Gould to not pass this ordinance.[2] In his January 4th letter to Gould, Henderson declared the inherent issue of passing a segregation ordinance, and the dangers it would have on both the Black and white community of Falls Church. It is unknown what Gould’s response was to Henderson because no matter the response, Henderson organized local Falls Church and Tinner Hill leaders to organize the CCPL.[3] Meeting at Joseph Tinner’s home on Tinner Hill, the CCPL outlined their fears of what could come if passed, named their leadership – with Joseph Tinner as president, their ambitions to confront the Council and the ordinance, and they wrote a letter to read in front of the council.

This letter written by the CCPL under the name of Colored Citizens Committee was read by E.B. Henderson on January 11th in front of the town council.[4] The letter clearly states the confusion as to why this law needed to be passed, the damage it would cause to the community and the urgency to rescind their vote to pass the law which would go into effect in January of the next year.[5] The response from the Town Council is unknown, the only mention of this discussion is treated as a minor note in the grand scheme of the January 16th meeting minutes, “A representative of the colored citizens being present the mayor requested to make known their desires.”[6] Following the presumably cold response from the white-led Town Council, Henderson took to writing W.E.B. Du Bois of the NAACP to seek assistance.[7] This letter sent on January 20th would begin a three-year period of interaction and eventually acceptance of the CCPL as a NAACP branch.

While the NAACP was not able to provide Henderson and the CCPL much assistance in January 1915,[8] this did not stop the CCPL from continuing their fight against the segregation ordinance. They took matters into their own hands over the next months and years to resist the ordinance, the CCPL wrote letters of protest to the mayor and all members of the Town Council of Falls Church. Following the passage of the ordinance the CCPL hired Attorney Thomas L. Jones out of Washington D.C. in an effort to prevent the ordinance from being enforced.[9] In November 1915, the CCPL and their attorneys were able to get a pause on the ordinance with the help of a decision by the local Circuit Court of Fairfax while waiting for other court rulings.[10] However, later that year in June 1916 after appeals by the Town Council, this was overturned by the Circuit Court of Fairfax. This decision was sent to the Town Council in the form of a typed letter and declared the legality of the ordinance.[11]

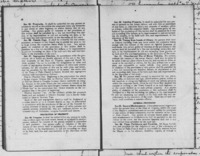

Either in an act of hubris and obstinance in the face of Tinner Hill and the Black community’s resistance, or with foresight of the incoming ruling by the Circuit Court of Fairfax, two months later the Town of Falls Church had already printed the segregation ordinance in their upcoming law book. This new edition of the Laws of the Town of Falls Church, Virginia was first shown in Town Council meeting minutes on April 10, 1916. Therefore, the printing of this law book including the segregation ordinance on page 40, sec 87 was printed after decision by the circuit court to nullify the law, and before the June 1916second ruling by the circuit court to reinstate the law. The Laws of Falls Church were therefore released in October 1916 with the law printed on page 40, section 87 under the subsection “Protection of Public Order.”[12]

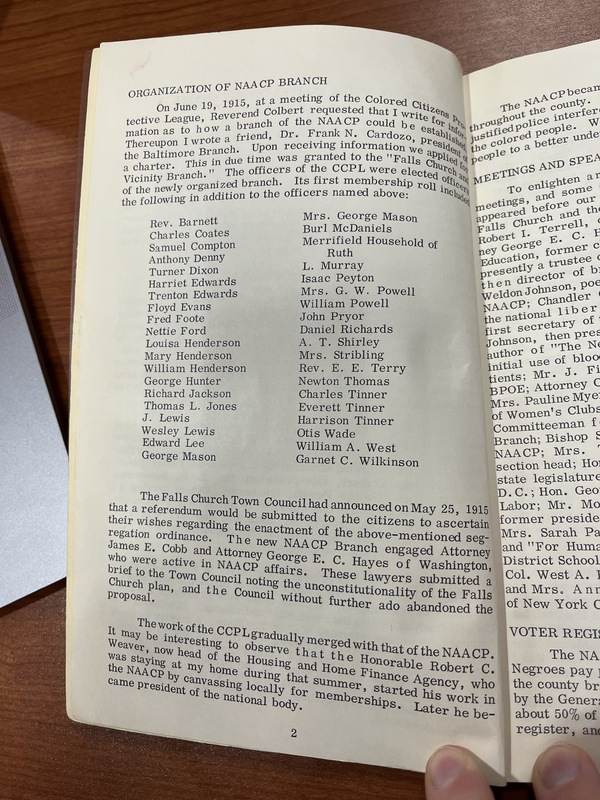

While in the short term the CCPL had lost the battle, their fight had drawn the case out long enough that the segregation ordinance was only in effect for around a year. Brewing in the background, Buchanan v. Warley was being argued and the constitutionality of segregation ordinances were being decided in real time with Falls Church’s ordinance. Ultimately decided in November 1917 with the Supreme Court case Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917), Buchanan v. Warley helped to mark a decisive victory for the CCPL as their efforts to gum up the process of implementing the segregation ordinance were finally resolved with the constitutionality of all segregation ordinances decided by the Supreme Court.[13] In the following years the CCPL continued to aid the Black communities and residents of Falls Church, and finally in 1918 their wish to be chartered as a branch of the NAACP would be granted. On their original application, the 35 names listed demonstrate the versatile and skilled positions held by all members of the small but mighty Falls Church and Vicinity Branch of the NAACP (Fall Church NAACP), the first rural branch of the NAACP.[14]

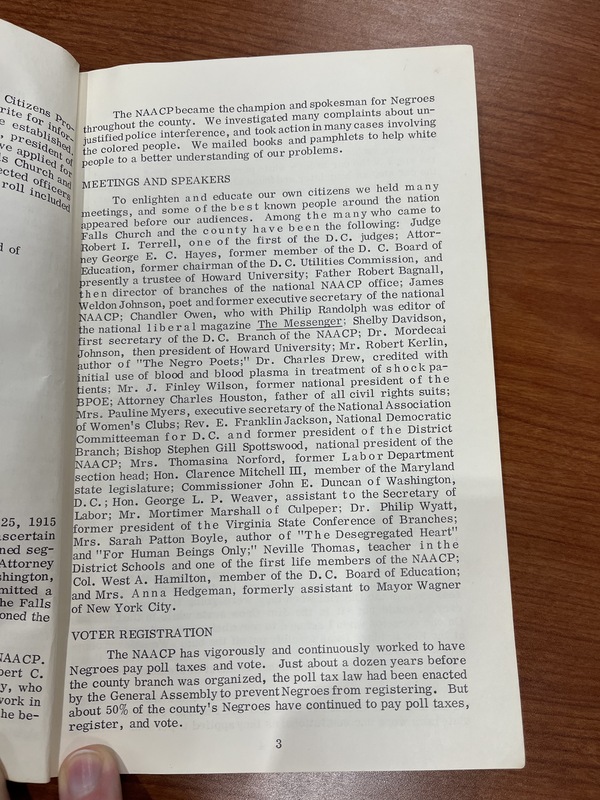

Listed in the short book written by E.B. Henderson in 1965, History of the Fairfax County Branch of the NAACP, the work of the Fall Church NAACP was broad. It worked to fight segregation in train cars, to improve Black voter registration in Falls Church, and to work with local youth and Black communities in a variety of ways. Other work included investigating police brutality and unjustified police interference, as well as taking action in local courts to represent Black clients.[15] The work of the Falls Church NAACP eventually moved from just representing the Falls Church and Tinner Hill community specifically as over time it integrated local branches of Black organizations. In an effort to appease these groups and provided a general group, the name was changed to the Fairfax County Branch of the NAACP (Fairfax NAACP) in 1920.[16] The Fairfax NAACP stands to this day as a beacon of the resistance and ingenuity of the Tinner Hill and broader Black Falls Church community in their effort to fight injustice and reject segregation.

Minor community organizations over the next decades continued the early fight of Tinner Hill following their creation of the CCPL and Falls Church NAACP. One key organization was the Fairfax County Colored Citizens Association (CCA). Formed in 1928 by a significant contingent of Tinner’s and other local community members from southern Falls Church, the CCA continued to represent Black Falls Church, and the broader Fairfax County Black community in a variety of ways. Their 13th anniversary booklet provides insight into their work over their first decade, making a note of the accomplishments and ongoing work.[17] Their work models similar actions and goals to that of the Fairfax NAACP and its predecessors the CCPL and Falls Church NAACP. Critical victories in these early years parallel the voter programs, NAACP educational equality work, and infrastructural improvements efforts.[18] Their work highlights the ongoing process of fighting slow violence in the Black Falls Church community, as well as the rising tide of civil rights and Black activism in the coming decades to fight structural racism. The work of these local community organizations run by Tinner Hill community members allowed for Tinner Hill to maintain its place, and resist displacement.

While the early decades of the twentieth-century brought with it challenges for Tinner Hill, the leadership by the Tinner Hill community and broader local Black community resisted total displacement, while building local organizations that stood for many years including the Fairfax NAACP which still exists today. Their accomplishments and drive for equality meant that even in the face of physical displacement and the creeping growth of development in the middle and later decades of the twentieth-century that Tinner Hill was able to physically maintain its place in Falls Church. With the coming turn of the century, development brought with it meaningful change to the landscape of Falls Church, but Tinner Hill remained, a secluded community that contrasts the modern subdivided neighborhoods that coat the geography of Northern Virginia.

This seclusion is both an effect of the work of Tinner Hill’s early pioneers in civil rights and anti-segregation activists of the Tinner and Henderson Families (not to mention all other local Black families who aided in these efforts) on Tinner Hill, as well as an aftermath of the Lee Highway being developed, splitting Tinner Hill and affecting the geography of the community that surrounded it. A considerable amount of the focus on Tinner Hill centers on the work of organizations and experiences of the early twentieth-century. However, it is important to discuss the evolution of these Black-led organizing efforts to sustain and remain in place in the face of slow violence, displacement in place and physical displacement.

While significant community efforts on the scale of the CCPL organizing in Tinner Hill may have dropped off in the later decades of the 20th century, the arrival of E.B. Henderson’s grandson in 1993 sparked a new organization for the preserving of Tinner Hill and its surrounding community. Edwin Henderson II moved to Falls Church in 1993 – returning to his grandparent’s home and continuing a long line of then 7 generations of Henderson’s in the area.[19] In 1997, Henderson II began establishing the Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation in an effort to preserve, celebrate and archive the early history of civil rights work in Northern Virginia, Falls Church, and Fairfax County.[20] The Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation (THHF) has acted as a keeper of Tinner Hill’s history, and legacy, all the while positioning the community for preservation into the future through multiple avenues.

Their earliest work to sustain the community began with sponsoring the local Tinner Hill Music Festival, a local festival that had been put on for four years by the time the THHF was established, which has grown in size since its early years.[21] The THHF continued work to maintain the heritage and history of Tinner Hill with a flurry of action from 1997 to 2000. Beginning in 1999, the THHF began attaining original plots of land at 106 and 108 Tinner Hill Road owned by Joseph Tinner. The original purpose of the land would be to rebuild the home and use it as a museum, though sometime after THHF acquired the rights to use the land these plans changed.[22] Today on 106 Tinner Hill Road lies the “Tinner Hill Historic Park” with the picnic pavilion and the Zig Zag Monument – which follows the proposed segregation lines, with a historic site marker from the Commonwealth of Virginia.

The crowning achievement of the THHF is the Tinner Hill Monument built in 1999. This monument resembles arches and stonemasonry done by Joseph Tinner, who worked as a professional stonemason. This arch was built using all pink granite quarried by Joseph Tinner, all of which was sourced over the span of two years by the community of Falls Church.[23] The arch stands as a testament to the community, its resistance to displacement, and outlines the history and people who labored to protect the Black communities of Falls Church. It marks the land with a visual reminder of the work done in Tinner Hill, by Black residents of Falls Church, and their descendants to maintain community in Falls Church and Tinner Hill through great odds.

The work of the THHF has been instrumental in maintaining Tinner Hill and the heritage of Black organizing in Northern Virginia, Falls Church, and Fairfax County. Currently, as of February 2024, work is being done to establish a historical district in Tinner Hill/Falls Church, in response to “a culmination of the efforts of the Falls Church Historical Commission and the Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation.”[24] Comprised primarily of what was defined as District 1 in the original 1915 segregation plan, this historic district plan submitted to the City Council of Falls Church hopes to “celebrating the district through creative urban planning and urban design tools,” while exploring: partnerships with the THHF for promotion of the district, potential archaeological significance, and promoting tourism – among other examples.[25] This would further designate the historic efforts achieved in the area through historic district designation.

Though the work of local community resistance, and community maintenance efforts have helped to retain the historic nature of the Tinner Hill family land, the broader community surrounding it has seen dramatic shifts. Comparing the land owned and maintained by Tinner’s on Tinner Hill to the land surrounding it reveals stark contrast. Development has turned most of the area into commercial locations. The land behind the Tinner Hill Monument arch, located just north of the Tinner Hill family homes, has been redeveloped from a commercial strip into a multiuse high-end apartment and commercial complex. The monument now abuts the entrance of a Target store built into the multi-use complex, representing the historic struggle of maintaining Black spaces against the consistent push for development, and now redevelopment

Actions to consistently develop and redevelop land, fueled by the myth of progress, underscore the need for historic sites like the Tinner Hill Monument, and more importantly groups like the Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation. These architectural additions mark the land. The structures enshrining the presence of Black geographies that often forgotten and displaced by development pressure. The sustained presence of Tinners, Hendersons and other Black families in Falls Church has allowed a process of remembering, and sustaining presence, all the while resisting and foiling displacement and slow violence, hopefully for generations to come.

[1] Anna Buczkowska, Basem Saah, and Professor Paul Kelsch, “Tinner Hill, Virginia: A Witness to Civil Rights” (Blacksburg, VA, Landscape Architecture Program, Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University, 2011): 20.

[2] Edwin Bancroft (E.B.) Henderson, “Letter from E.B. Henderson to Councilman, Dr. J. B. Gould,” January 4, 1915, Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library.

[3] “Falls Church Committee Meeting” (Meeting Minutes, Tinner Hill, Falls Church, VA, January 8, 1915), NAACP Collection, Library of Congress, http://100yearsblackfallschurch.org/items/show/287.

[4] “Town Council of Falls Church Minute Book” (Vol.1. 1875-1921), Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library: January 11, 1915, page 218.

[5] “Letter Written to the Falls Church Town Council on Behalf of the Colored Citizens Protesting the Establishment of ‘Segregation Districts.,’” January 8, 1915, Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library.

[6] Town Council of Falls Church Minute Book” (Vol.1. 1875-1921), Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library: January 11, 1915, page 218.

[7] Edwin Bancroft (E.B.) Henderson, “Letter from E.B. Henderson to W.E.B. Du Bois,” January 20, 1915, Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library.

[8] Secretary of the NAACP, “Response from Secretary of the NAACP to E.B. Henderson,” February 1, 1915, Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library.

[9] Edwin Bancroft (E.B.) Henderson, History of the Fairfax County Branch of the NAACP (NAACP Fairfax County Branch, 1965): 1-2.

[10] Town Council of Falls Church Minute Book” (Vol.1. 1875-1921), Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library: November 8, 1915, page 249; “Civil Rights History & Tinner Hill,” Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation, February 15, 2018, https://www.tinnerhill.org/educational-resources/2018/2/15/civil-rights-history-tinner-hill.

[11] Town Council of Falls Church Minute Book” (Vol.1. 1875-1921), Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library: June 12, 1916, page 263-264.

[12] The Town Council, Laws of the Town of Falls Church, Virginia: The Town Charter Amended Feb., 5, 1916 and The Town Ordinances, ed. John F. Bethune (Falls Church, VA, 1916): 40.

[13] Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60 (1917).

[14] Colored Citizens Protective League, “Application for Charter of The Falls Church, Va. Branch of the NAACP,” June 18, 1918, Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library; NAACP, “Executive Authorization for the Formation of the Falls Church Branch,” July 17, 1918, Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library.

[15] Edwin Bancroft (E.B.) Henderson, History of the Fairfax County Branch of the NAACP (NAACP Fairfax County Branch, 1965): 3-4.

[16] Edwin Bancroft (E.B.) Henderson, “Letter from E.B. Henderson to Miss Ovington,” April 2, 1920, Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library.

[17] The Colored Citizens Association, “The Colored Citizens Association Anniversary Booklet” (The Colored Citizens Association, June 8, 1941), Mary Goins Roots Collection, Fairfax County Public Library, https://fairfaxaahi.centerformasonslegacies.com/items/show/207.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ellen Nakashima, “Festival Celebrates Area’s Past,” The Washington Post, June 6, 1996.

[20] Gwen Jones, “Edwin B. Henderson II: Shedding Light on the History of Civil Rights | Family Services,” Fairfax County Virginia - Golden Gazette, February 20, 2024, https://www.fairfaxcounty.gov/familyservices/older-adults/golden-gazette/2024-02-edwin-b-henderson-ii-shedding-light-on-the-history-of-civil-rights.

[21] Ellen Nakashima, “Festival Celebrates Area’s Past,” The Washington Post, June 6, 1996.

[22] “Resolution to Encourage the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority to Purchase the Johnson Property on Tinner Hill to Honor Those Who Fought Segregation,” Pub. L. No. Res. 99-22 (1999); Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation, “Tinner Hill Heritage Home,” 1999, Falls Church History Room, Mary Riley Styles Public Library.

[23] “Our Historic Preservation Efforts,” Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation, https://www.tinnerhill.org/what-we-preserve.

[24] “Establishing the Tinner Hill Historic and Cultural District in the Falls Church Comprehensive Plan | Falls Church Pulse,” Falls Church Pulse, February 9, 2024, sec. Tinner Hill, https://fallschurchpulse.org/tinner-hill-historic-and-cultural-district/.

[25] City Council of Falls Church, “THE TINNER HILL HISTORIC & CULTURAL DISTRICT (AMENDMENT TO THE COMPREHENSIVE PLAN)” (City of Falls Church, January 16, 2024), https://fallschurch-va.granicus.com/MetaViewer.php?view_id=2&clip_id=2536&meta_id=128971.